In the grand tradition of Tom Robbins and Kurt Vonnegut, Julie Townsend has created Valgooney Gore, a wealthy PETA-esque revolutionary whose crusading attempts to right the wrongs created by narrow minds allies her with a lesbian real estate broker from Charlotte, North Carolina, about to close the deal of the century. Along with this dynamic duo, Townsend adds an unlikely but completely compelling third, the Kennedy no one speaks of, Rosemary, lobotomized and discarded by her unscrupulous father. An ambitious and hilariously audacious writer, Julie Townsend manages to create a compassionate, funny, and wistful allegory of this most interesting era in which we live. Townsend¹s social satire goes down easy but lingers like a hard-won life lesson.

–Robin Hemley

Director of the Nonfiction Writing Program at

the University of Iowa; winner of a a Guggenheim Fellowship

Rosemary Kennedy–institutionalized and lobotomized–has a secret but no way of revealing it. Leslie Ryan, mourning the death of her partner Andrea and struggling with her mother’s contempt, is desperate to hang onto her commercial real estate business in a recession that isn’t getting any better. Valgooney Gore seems hellbent on saving the bluefin crab population from dinner plates throughout Myrtle Beach. In Seafood Jesus, their lives converge in surprising and unlikely ways. Edgy, witty, and unexpectedly poignant, their voices buzz with Southern quirkiness and loveable redneck charm, delivering both hard-edged laughter and raw truth. Julie Townsend’s deftness in creating diverse and fascinating characters with familiarly different life stories is clearly evident in this smart caper across time and place.

–Barbara Presnell

author of Piece Work

Life flashes–a secret lobotomy or a lobotomy secret? Emotional terrorism revealed in a voice from beyond: the voice of Rosemary Kennedy, who tells what has remained unspoken–the infamous secret behind the famous story. Rosemary’s voice stops in a world where fathers transform their daughters with disastrous results. Decades later, seeing victims of emotional terrorism in the wreckage, a wealthy woman starts a national support group for anyone abused in the name of the conservative religious right. The world turns on its head as horror gives birth to offbeat humor in the form of a Seafood Jesus, ready to right the wrongs for victims who can’t speak for themselves.

–Aimee Parkison

author of Dark Horses,

winner of the Kurt Vonnegut Fiction Prize

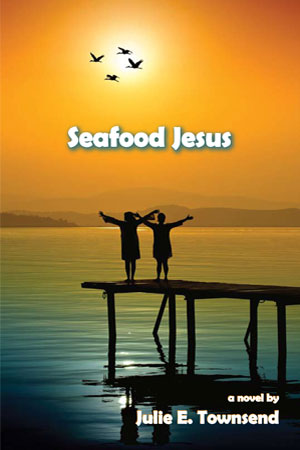

Seafood Jesus

Valgooney Gore, a year-round, naturally tanned, lean, and actual-blond, knew she had cut it close this time–barely escaping the Coast Guard–their lights cutting through the channel’s brush like a machete. Just yesterday, the Myrtle Beach Grand Strand’s Sun Times News reported that the reward was raised to twenty-five thousand dollars. “The Crab Bandit,” the article read, “has made fresh crab meat a delicacy in this area.” As she cut that article out like all the others she had collected for two years, she said aloud, “Someone please tell me who our heroes are…movie stars and sports figures? A bona fide hero saves lives, and when necessary, throws ‘fuck it’ to the wind,” and not a pop star who managed to make millions on some more of the same.”

When the “crab bandit” was mentioned on the local news, the reporters speculated like all news people did, with an air of authority as thick as Myrtle Beach’s humidity. “The culprit,” a reporter said on the 5:00 “first” news, “is selling the crabs and making a fortune.” By 5:30, Channel 8 claimed it had the inside story from a seafood distributor.

“Our sources tell us that these people are attempting to take over the entire market by robbing free enterprise.”

She wasn’t “robbing free enterprise,” she thought. She was just a seafood Jesus. Okay, maybe the crabs wouldn’t have eternal life, but at least for a while, she saved the crabs from sautéing, dipping, or boiling to death. Only she never intended for her mission to get notoriety, but she just didn’t know how else to save them, like she had tried to do with the horses used for glue on postage stamps. For that one, she held a protest at the main post office in Myrtle Beach: posters painted with horses lying on their backs; hoofs straight up in the air; captions reading, “Stop the violence,” and posters of Uncle Sam pointing at his ass, with a caption: “Glue this.” Two hundred like-minded people showed up for that protest. Unfortunately, that anti-glue protest didn’t move beyond the state line, unlike the Tea Party gatherings. Though she didn’t agree with a group of people who thought that they were replicating history, she at least admired how the nucleus of the movement were able to rally millions. She had given up trying to guess what exactly pissed off the sheep-following public. Instead she didn’t count a protest or movement successful unless it was capable of altering some minds. She thought that she had done so with making people aware that the stamps they slapped on envelopes used to be a race horse that they may have seen on television.

For the glue protest, she was thrown in jail for the night because she refused to leave the premises. The police cited her for “disorderly conduct.”

Earl and Lola Jenkins had bailed her out that time. She was sure that wouldn’t be the last time; however, she had decided then, that, she preferred to lurk in the shadows of the numerous causes she had instigated, funded, and seen played out in the media, like the woman who had started “pay it forward.”

She wondered, though, when she was almost caught, who was more stupid? Her, for almost getting caught, or the Coast Guard, for not checking the engines along this part of the channel? Not that they could make an arrest for a hot engine, but they could have brought her in for questioning.

She knew it wasn’t right to destroy others’ property, but it was more cruel to kill animals. Sometimes she thought it was odd that the same people who doted on their pets, ate other animals and never once thought about the similarities between their cats and a little fried chicken. Just because something was a mass enterprise production, didn’t mean it was void of feeling.

She probably would not have thought about destroying the underwater cages, if it had not been for her hearing some vacationers describing their crab catch and then seeing some legs on display in the grocery store. The barbarianism got to her.

So she began zipping throughout the Intracoastal Waterway, looking for the floating, plastic milk cartons that indicated a cage was directly underneath. She’d hoist the cage into her flatbed boat, water gushing out like a broken dam, while she snapped open the door of the cage. Before the crabs could make their escape, she’d lift it again, and tilt it off the side of the boat until she heard the last plop. Then with a surgeon’s precision, she’d cut the cage apart and let it sink back into the water under the bobbing milk carton.

Last night she had only been able to destroy one cage before she heard the Coast Guard’s boat moving slowly through a nearby channel. She saw their lights shining down the channels like they were in Vietnam on reconnaissance patrol. As she leaned over the boat and twisted the wet, dripping metal with her pliers, their rotating light shone on the end of her boat. The light stopped for a second.

She shook the cage hard and heard the crabs falling into the water. As she kept shaking the cage, she used her other hand to turn up the engine. Just as the Coast Guard’s light began its counterclockwise circled scope, she tossed the cage into the marsh and sped off into the channel. She knew that their boat was too big to make it down this particular channel, but they could catch her as she came back to the main channel.

It wasn’t that she feared getting caught; she just didn’t want to hear what Lola Jenkins, Earl’s wife, would have to say about it. When Lola was mad about something, there wasn’t a planet far enough away to escape to. Valgooney closed her eyes and could see the entire drama coming in three acts. Short, squat, and sixty-five-years old, Lola would first invade Valgooney’s face space, standing so close to her that if either one would move a quarter of an inch, their lips would touch. Valgooney didn’t care for the spittle that shot out from the corners of her mouth like missiles. She could feel them land on her face–hot sprinkles– like a sharp summer drizzle. The drizzle moved to the verbal; the verbal to gesticulation, like a dictator at their own rally.

When she wanted, Lola could turn that knob within herself and burn on high for as long as it took to get her mission accomplished. Add a little righteousness to it, and it was a miracle if the person could ever emotionally walk again. Lola, Valgooney sometimes thought, was the kind of woman who could make a man go limp with just a look, a snort, or those words that ate its own, inside out.

At least earlier tonight, Lola was on a slow simmer.

“What’s that you bringin’? Goin’ get me in trouble tonight,” Earl said, sitting in a white rocking chair on their wide front porch.

“Actually, I thought it might sweeten Lola so she wouldn’t pick on either one of us.” She walked up the stone steps. “All yours.” She handed him the bottle.

Earl set the bottle down, stood up and gave her a hug. “How you?”

“Fine.”

Earl bent down towards the table, picked the bottle back up, and held it close to his right eye. “Gettin’ fancy on us?”

“I almost didn’t bring it because I wasn’t sure if she was letting you get away with having a drink now and then.”

Earl glanced over his shoulder towards the open front door. “Way she tell it, make somebody think I’m out cattin’ around seven night a week. Ain’t so. Ain’t never been so, and she know it. Me havin’ a drink now and then about the only thing left she can complain about.” He picked up the bottle. “Fact is, I think she get downright bored when she don’t have somethin’ she can complain about.” He looked back over his shoulder again. “Come on, let’s get her goin’.”

They walked through the doorway and into the wide foyer. Valgooney looked at the shiny hardwood floors. “Did you refinish these?”

“Lola made me do it last week.”

They walked through another doorway and into the large kitchen. Sometimes, when Valgooney hadn’t visited for a while, the size of their kitchen was shocking. Most everything was large compared to her trailer.

Valgooney did a quick 360-degree look at the kitchen: the glossy white walls and Waverly pattern melded with the hanging plants and utensils packed neatly in wooden holders.

Lola had her back to them, stirring something in one of the three tall metal pots on top of the stove.

“Lola, look what Valgooney bring,” and he held up the bottle.

Lola, dressed in a light blue dress with black buttons down the front and a black stripe that outlined the collar, turned around.

“How you been honey? Ain’t seen you in a few weeks.” They hugged.

“Told Earl you must be workin’ on another project, ’cause when you do, I know you lock yourself away in that trailer and except for your runnin’, you a ghost.”

Not waiting for an answer, Lola walked back over to the stove. She picked up a large plastic spoon lying in the middle of the stove in a heart- shaped dish and resumed her stirring. “Cookin’ you a new vegetarian dish called ‘chick pea and artichoke stew.’ The nurse at my doctor’s office recommended it when I was havin’ my blood pressure checked.”

Valgooney sat down in a chair at the kitchen table. “Smells wonderful. I hope it wasn’t too much trouble.”

Lola kept stirring but turned her face to the side. “Don’t you worry none if it was.”

“What did the doctor say about your blood pressure?”

“What he always say, say it too high, but I told him I was doin’ what I could without starvin’ myself to death. Told him I’d never have a body like my husband. Told him God didn’t intend my body to be no toothpick. I was made a pear, not a toothpick.”

“Lola, you want some of this wine?” Earl had the bottle on the counter and was pulling on the corkscrew.

She nodded. “Get them nice glasses out of the china cabinet.”

Earl pulled out the cork and walked into the adjoining dining room and returned with three crystal goblets. “You been readin’ about the Crab Bandit? They getting’ real busy now,” he said.

Valgooney didn’t look at him or answer.

Earl poured the red wine into each glass. Then he picked up one of the glasses and the wine sloshed from side to side as he walked over to Lola. “Here, Honey.”

“Can’t you see I’m cookin’?”

He kissed her on her cheek. “You cookin’ even when you ain’t.” He turned and winked at Valgooney.

Julie Townsend

Julie Townsend