poems by

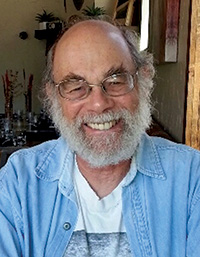

Robert Cooperman

ISBN: 978-1-59948-725-0, 92 pages, $15 (+ shipping)

Release Date: April 23, 2019

$15.00

poems by

ISBN: 978-1-59948-725-0, 92 pages, $15 (+ shipping)

Release Date: April 23, 2019

Robert Cooperman’s latest collection is Their Wars (Aldrich Press). His chapbook, Saved by the Dead (Cooperman’s love letter to the Grateful Dead) has just been published by Liquid Light Press. In the Colorado Gold Fever Mountains (Western Reflections Books) won the Colorado Book Award for Poetry. Cooperman’s work has appeared in The Main Street Rag, The Sewanee Review, and The South Carolina Review. Cooperman lives in Denver with his wife Beth.

Robert Cooperman’s latest collection is Their Wars (Aldrich Press). His chapbook, Saved by the Dead (Cooperman’s love letter to the Grateful Dead) has just been published by Liquid Light Press. In the Colorado Gold Fever Mountains (Western Reflections Books) won the Colorado Book Award for Poetry. Cooperman’s work has appeared in The Main Street Rag, The Sewanee Review, and The South Carolina Review. Cooperman lives in Denver with his wife Beth.

Robert Cooperman’s full-bodied sensual language of imagery lights up the freedom, drugs, and soul-grinding hunger of the “summer of love,” as hard rock and the Beat generation redrew our political and social landscape. Pack your back-pack, your dog-eared copy of Homer’s Odyssey, and join him in hitchhiking across England and Northern Europe, catching rides and sharing work, food, literature, love and lonely starry nights among strangers somewhere between peace, hallucinogenics, and the Vietnam War. ~Jared Smith, Author of Shadows Within The Roaring Fork

That Summer doesn’t have the heft of an Australian walkabout, but it is definitely a rite of passage, especially for a twenty-something guy from Brooklyn determined to hitchhike through England and Scandinavia in 1969 with scant possessions but money to keep him in weed and hash. He depends on his thumb to get him everywhere. Cooperman becomes part of a phalanx of young adults, many of whom are headed to a music festival on the Isle of Wight, headlining Jimi Hendrix. I trust Cooperman to be a reliable narrator every time he accepts a ride or ends up with strangers he can’t communicate with or is obliged to eat pork for the first time (he’s Jewish) so he won’t offend his host. Cooperman’s adventures have memorialized a summer for our reading pleasure. ~Nancy Scott, author of Running Down Broken Cement

Step right this way! Robert Cooperman takes us back—and forward—in his wonderful new book. 1970, was that yesterday? The book is no travelogue but a rethinking of place and time—and its effects upon us long after we are back home in our usual lives. It also is a study of memory, what shines and lasts regardless of time passing. Cooperman has a gift for finding humor and asking good questions. A pleasure! ~Kenneth Pobo (author of Trina And The Light, Loplop in a Red City, and Bend of Quiet)

God, the things we said!

Though no dumber, I guess,

than terms kids used before or since,

but now I cringe, to hear, “Far out, man,”

great, if imprecise distances indicative

of astonishing “cosmic” effects.

And everything was “Groovy,”

meaning “in the groove,” “delightful,”

and “mellow,” as in, “Mellow Yellow,”

the bogus claim that scraped banana peels

were hallucinogenic, and of course the advice

to “Mellow out,” or relax, now replaced by,

“Chill out” or “Chillax,” though neither

sounds nearly as mellifluous.

And cops were “Fascist pigs,” “Fascist”

covering everything we hated, and not

necessarily to do with Mussolini and Franco,

though nowadays we could say the same

quite accurately of Trump and his minions.

But more pleasantly, a girlfriend or boyfriend

was, “My old lady” or “My old man,” to indicate

they were comfortable as broken-in sandals;

or women were “main squeezes,” which sounded

luscious back then, sexist now, but not as bad

as, “Chicks,” from which term I now cringe.

And “Psychedelic,” wasn’t just LSD,

but anything strange and wonderful;

and “Surreal” was, looking back,

that whole era: thrilling, but terrifying:

Vietnam’s sword suspended over our lives,

its cord fraying fast, so best, as Janis sang,

to “Get it while you can.”

He’d been dumped by his wife

and was taking a long, head-clearing

drive to the coast, and when he stopped,

my thumb lonely in the breeze—

he talked, and I listened: payment

for the ride: he was an architect, successful,

until the clichéd gorgeous younger woman.

“I fell for her as if someone had pushed me

off a scaffolding,” he sighed, “and crashed

into divorce court.” The woman left him.

His wife, “Sued me for everything

except this car,” an MG that danced around

curves and could rocket-ship straightaways.

“I can’t see my daughter without supervision.

She’ll grow up hating me, not that I can blame

my ex-wife, after what I did.” All of this Ancient

Marinered to a stupid kid barely twenty-three.

When I asked if he wanted company to the coast,

he said he’d be visiting a friend who’d made

the same mistake. We shook, and he was gone.

And as young and dumb as I was, I worried

if there really was a friend at the end of his road,

or something colder, wetter.

The aroma everywhere,

the city Katmandu high.

Mixed in, the stink

of tobacco: how weed

was rolled in Europe,

to help the grass

go further. I never knew

if it was the ookey-dookey

or the cancer flecks

making me high.

One night, joints

were passed around

like bags of popcorn,

impossible to tell

tobacco stench

from marijuana bouquet:

air in the rock club

smoggy as rush hour L.A.

in a temperature inversion.

The smoke was sinking

from the ceiling like an evil gas,

when the mixture got to me,

the way, when I was ten,

some wag of an uncle

gave me a lit cigar,

and everything I’d eaten

rushed to the surface.

When my head cleared,

I was alone with music

and bodies throbbing

all around me, and a long

walk in the dark back

to the youth hostel.