A Passing Conversation

I sailed into Marmaris, Turkey, in late spring from my base in Rhodes, Greece. Mountains nearly enclose Marmaris Bay. When you reach the mouth or cut of the bay, the aroma of rich loamy soil and the ever-present perfume of pine strikes you. This is the smell of Western Turkey. Its neighbor Greece has a sunbaked rock smell with light wafts of fragrances like burning sage and rosemary. Making the richness of Turkey even more inviting.

A great swarm of honeybees greeted my boat, a CT 54 ketch rigged charter yacht in the cut. They lit in the coils of line, cushions, sails, and walked about the deck. After a few minutes, satisfied with their boat inspection, they flew back to their hives as quickly as they arrived. A couple of bees hang around for the ride into the bay, attracted to my fear generated pheromones. They lounged menacingly about the cockpit. They have stung me a lot in my life, and I do not fare well. I think the oil in the teakwood decks attracts the bees. But it could be magic, or it could be Western Asia just saying “Günaydın!”

Layered with stories, myths, civilizations, gods, and more intertwining nuances, Western Asia has more threads than a Turkish carpet. The layers of history leave one profound impression: these people are very industrious at creating civilizations.

At the south end of the bay, there is a modern marina, boatyard, and the vibrant old town market of Marmaris. Big hotels dot the northern shoreline. They added an airport several years ago which spurred tourism and development. From Bodrum airport to Marmaris, the trip took four hours by taxi with the new highway it is forty minutes. The new airport is only twenty minutes away from the port. The Phoenicians once rowed and sailed that distance in a day. Evidence of their presence is everywhere, along with Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Ottomans, to mention a few civilizations. It is no wonder once you walk a little way out of town; you are in rural Turkey. It is a kind of time travel. They view modernism with a wary eye. Foreigners are especially suspect but graciously received. There is a genuine sense that the Turkish people understand empires and civilizations are just fleeting moments in passaging time. The Shakespeare quote, “There is a history in all men’s lives.” is à propos as a place to understand. I have always had a sense that history informs the average person more intensely on the black loamy soil of Western Asia than in many other places on earth. For the Turk, history is intuitively present.

My old friend Omar directed me to a slip via VHF radio. Omar is a big, burly man with a sweet disposition. We met ten years ago, and he has been my agent in Turkey.

An agent finds you a slip in the marina when there are none. He clears us into customs and immigration as our representative. He makes money along the way by charging reasonable fees. If I need a part for the boat or a dinner reservation, Omar is my guy. Agents are worth every penny. They save you time and money as well as provide security. Having a paid representative to stand between you and your million-dollar yacht and unscrupulous officials is wise.

Omar hustled down the quay. His imposing stature cleared the German tourists out of his way, as if he were a madman. Omar waved his VHF radio above his six-foot four frame, using the antenna as a pointer. I would have to slip my boat to a specific space between two gulets. It was a tight fit. He was a man very much in charge.

Leases and tradition have monetized the imaginary spaces along the quay. A carpet seller sitting on the dock is paying rent to Omar for a guaranteed space. Omar distributes the rent monies to the local officials. Throughout these transactions, he takes a slight cut in a finely balanced and respectful process.

Docking a boat is theater in a port. Omar reached the spot on the quay where my stern would finally rest. The crews from the gulets looked at Omar for a sign of confidence in the captain docking his yacht between their precious, finely painted, and polished boats. Omar was happy. They relaxed, understanding the signs of confidence in Omar’s face. They tended to their fenders with some confidence that I knew what I was doing. Translation: No screaming or offering unwanted advice on docking my boat. In this part of the world, everyone on the dock knows how to dock a boat even though they have never docked a big boat. The antics can unnerve a green sailor.

I slipped my boat between the gulets without incident. The exhaust water from my motor burst rhythmically, gaining volume as I got closer to the quay. A blind person could dock a boat stern too just by the sound and pitch of the exhaust hitting the water. My mate tossed the lines to Omar, who expertly tied them. We lowered the passerelle. Secured, Omar bound onto the deck and gave me a big hug.

Omar and I share a special bond. We are brothers. We served in the army as a paratrooper; Omar in the Turkish Army jumping into combat in Cyprus and me into Vietnam. We learned of our mutual past by accident. One day after arriving it rained, and we went down below to conduct our business. On the table were pictures I was sorting out to put in a new book. One picture caught Omar’s eye: Me standing with a M-16 on my hip posing in front of the Royal Thai Airforce base sign with members of my platoon. He pointed to the jump wings on my chest and burst into excitement, yelling, “Brothers!” “Brothers!”

Our relationship went from business cordial to special brothers. That day, Omar drank wine with me to celebrate this transcendent moment. He was Muslim and didn’t drink. After that drink, it changed our relationship forever. We were friends and comrades, Turkish and American brothers.

He invited me to dinner. He sent his son to guide me up to his house on the mountain. It was a new home. The area around the house was muddy. His son, maybe six years-old, waved and spoke to everyone in sight as we walked up the path. I was a brother and a boat captain. Association is a powerful mechanism in Turkish society, good and bad. We walked some way up the side of the mountain. The cobble stone path and whitewashed walls meandered like a drunken goat. Little gardens with basil, coriander, and rosemary grew in orderly lines next to tomato seedlings. Out near the steeper part of the mountain, children dressed in raggedy sweatshirts and red plastic boots picked blackberries from the towering wall of blackberry bushes. They enthusiastically waved to us. Thrushes scattered over their heads, screeching in protest.

Omar’s house had unfinished cinderblock walls waiting for stucco. Rebar protruded out above the walls. Later, I asked Omar why all the homes had rebar sticking up along the roof and walls. “Two basic reasons,” he said. “His father’s land was prone to earthquakes. They used rebar to secure the house from falling on their heads and one doesn’t have to pay the full tax on an unfinished house. Fifty years homes stand unfinished!”

There were three stories and five bedrooms sparsely decorated. The unpainted plaster walls made the house feel industrial. “It is a work in process,” said Omar assuredly.

Omar greeted me with a big hug. Omar introduced me to his father, mother, wife, four sons, and two daughters. The daughters spoke British English. Omar had sent them to school overseas. His boys would follow when they were old enough. Going to school overseas remains a significant status symbol in Turkey. Turkey has a well-regarded university system. Because Omar works with foreign crews, he adopted an internationalist view of the world. His father, although happy and proud of his son, could build such a fine house; was deeply suspicious of foreigners. He respected me because he trusted his son’s judgement; I was a paratrooper, (He fought in WWII.) And I was a sea captain.

The family and I gathered around the table. I don’t speak Turkish. Omar and his two daughters translated. Sometimes Omar would turn to his sons and ask them if they understood what I said. They nodded and kept eating. Omar concluded they didn’t understand. He prodded them a little. The girls laughed. Finally, the boys spoke one after another in understandable English. I applauded them. We laughed. Omar hoped they would lose their shyness. “Practice speaking!” He bellowed. “It is the only way to learn.”

After dinner, we sat outside on a bench against the whitewashed side of his house in the spring sun, drinking thick Turkish coffee.

In our conversations, we relived the certain moments of our youth. How we gripped the handlebars of our bikes as we raced down that steep hill. Where our manhood developed through our recklessness. Omar pointed down the mountain to the exact spot where he broke his arm. The rules were to be broken. We must pay dues. Many near catastrophes forged our shared daredevil sense of living. The similarities of our experience wiped away all the differences. Turk and American, Muslim and Christian seemed inconsequential.

We leaned into each other’s ears to whisper. We shared intimate details about that girl in school that drove us to near madness with desire. We searched our memory banks for that song that identified us as cool. Omar has always loved western culture, especially American culture. We recited bits from that show that tickled our fancies so long ago. Omar watched shows as a child, dubbed in Turkish from a German version. We laughed very hard about the misconceptions around Fonzie on Happy Days. I realized the morality of dating around was an unacceptable behavior in Turkish.

Omar told me of the importance of literary writers in Turkey. Ferit Orhan Pamuk was his favorite. He admired writers. We talked for hours. His oldest daughter, Tamer, carried a tray with two glasses of brandy for us. “Grandfather says you may have one drink to celebrate your friendship.”

“Is Grandfather celebrating as well?”

“No.” She smiled. “He says his arthritis is acting up and he will take a drink as medicine.”

They laughed.

Omar and I grew closer, laughed harder, and told more personal stories. We touched on our war experiences. Omar wasn’t open to confessional and emotional declarations. A man was a man. Simple. Nothing to talk about. He shared it with me. I shared it with him.

This was all a passing conversation. Connecting and learning about my friend made me feel a special affinity for Turkey, the country. Small slivers of understanding cast a certain clarity in an otherwise opaque picture of this complex and rich culture.

Then, like a bolt of lightning struck him, Omar shut down the conversation and offered to take me wild boar hunting the next morning. “Enough talk about us! We need an adventure to bond us in the now!”

For the record, I am not a hunter. Caught up in the moment as one does, and I agreed.

The next morning at six, Omar was standing behind my boat dressed in his army fatigues. We hit the road. We drove four hours up the Dalman River. This is some of the most beautiful country I have ever seen. It reminded me of the Upper Delaware River in the United States.

We stopped by a small rustic taverna. I thought I was in the middle of an American western movie set: horses, lances, stuffed boar’s heads, stuffed deer heads. This wasn’t an American movie set; this was a 17th century Turkish life in motion.

I mounted a very hairy horse. Omar shoved a lance into my hand. The lance was about eight feet long. Omar was giggling the entire time at my reaction. I asked where my rifle was? Our guide had a musket! Looking aghast and ready to quit this insanity, a pack of seven full grown Great Danes loped around the corner of the restaurant. The Great Danes would hunt and corner the boar. I would, because I was an American guest, ride into the melee and stick the boar with my lance. If I missed and the boar got away from the dogs, he would most likely attack, and the guide would shoot the boar as a last resort. I didn’t have confidence in the plan.

We rode for an hour. Omar came clean. Normally, Turks don’t hunt wild boar because of religious reasons, but his people were an exception. Hunting was about bonding, especially this kind of ancient hunting.

The dogs yelped and barked. They plunged into the thick brush. We followed, riding down a small animal path. My shaggy horse suddenly bolted down a slight path. I gripped what hair I could of the shaggy horse’s mane hanging on for dear life, my lance dragging behind us. Raked to the bone by prickly vines, broken branches and sharp thorns, the shaggy horse stopped. We were alone. Omar and the guide took a fork in the path in another direction. The shaggy horse seemed to find its bearings and bolted. We burst out into a small clearing. There, with its back hairs up and its twenty-inch tusks thrusting at two of the Great Danes, both bleeding, was a two-hundred-pound boar, giving no quarter. (As a note, I was thinking small pig this entire trip.) My shaggy horse reared up and charged the boar despite my prostrations to the contrary! I leveled the lance and drove it into the mouth of the raging boar. The boar ripped the spear sideways out of my hands. I fell off my shaggy, but brave, horse. The boar stumbled and laid down in a patch of ivy. He snorted a bloody gurgle, then died. Cut and bruised, I yanked the spear from the boar’s mouth. I screamed! “I hate death!” The Great Danes whimpered and licked their wounds, keeping close to me, unsure of our next move.

A few minutes later, Omar and the guide came crashing through the brush into the bloody clearing. Omar leaped off his horse and ran to the boar. The guide quickly checked his wounded dogs. The other dogs of the pack surrounded their wounded brethren and licked their wounds. There was concern with everyone. I stood at the center of the clearing. My lance pointing to the sky. Omar grabbed me by the shoulders and hugged me. “Brothers! True brothers?” He and the guide knelt on the ground and prayed to Allah.

I stood staring up through the canopy of tree branches at the evening sun peeking through the spring leaves, hesitant to be stabbed by my lance.

Three days later, I was reading a book in the cockpit of my boat when Omar came bounding up the gangway. He was there to invite me to his house for a dinner of wild boar. I said I really wasn’t interested in eating boar. He smiled and suggested Italian. We had a very pleasant dinner together. I drank a bottle of wine and Omar drank an Orange Fanta.

Speaking softly over his empty plate, he said, “Our stories are about the nuances of who we are and how we got here. Inside our lives, there are a series of undefinable moments that only we know have significance. As we get older, there seems to be this flooding of incidents that populate our narrative. These smaller incidents rarely have anything to do with major events, fighting in a war, buying your first house, killing a boar with a lance on a horse! We will always remember those sparkling bits. The significance lies in the passing of a conversation untouched because of its mundaneness. We’ll remember the day, whether it was sunny or cloudy, warm, or cold. We’ll remember the friendship and the vein of brotherhood it has opened for us. The experience you bring is in me and the experience I bring is in you. This richness of our lives comes from the little things in our passing conversations.”

He sat back in his chair and smiled.

“Brother,” I said. “Thank you. Teşekkür ederim.”

_______________

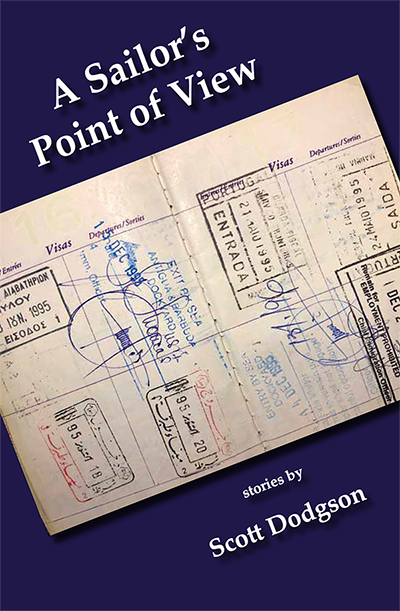

If you’d like to read the rest of this book, please order

A Sailor’s Point of View today at the Advance Discount price

and have it delivered to your door when it is released

in the Spring of 2023.

Scott Dodgson wrote the popular movies The Anna Nicole Story, Paris Hilton, Princess Paparazzi, and numerous other films and television shows. He has published a novel Not a Moment to Lose, a novella The Casket Salesman, and numerous short stories and essays. He has roamed the seven oceans sailing as far north as the Baltic Sea and Alaska and as far south as Kenya in the Indian Ocean and from South Africa to Chile in the Southern Ocean along 50 degrees south. His new novel The History of Water is forthcoming.

Scott Dodgson wrote the popular movies The Anna Nicole Story, Paris Hilton, Princess Paparazzi, and numerous other films and television shows. He has published a novel Not a Moment to Lose, a novella The Casket Salesman, and numerous short stories and essays. He has roamed the seven oceans sailing as far north as the Baltic Sea and Alaska and as far south as Kenya in the Indian Ocean and from South Africa to Chile in the Southern Ocean along 50 degrees south. His new novel The History of Water is forthcoming.