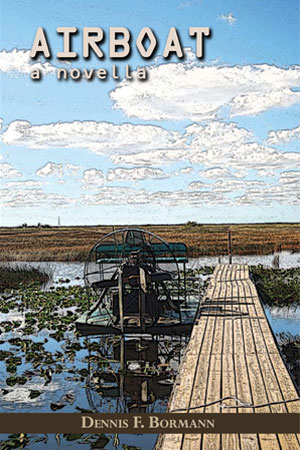

a Novella by

Dennis F. Bormann

116 pages, $9.95 cover price

($8 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-292-7

Released: 2011

Synopsis

Set in central Florida, on the back-waters of the St. John’s River, Airboat, tells the story of Roland, a young man trying to discover his past. A victim of childhood abuse until his teenage years, Roland is taken in as a ward of the state after his grandfather goes missing. It is discovered that the young boy has been building sculptures of river wildlife from the discarded scrap metal of marine motors and propellers from his grandfather’s boat repair business, and though he is socially and psychologically dysfunctional, his artwork is so impressive that the term autistic savant is applied to him.

Through the care of a passionate psychiatrist, Dr. Michael Turner, Roland starts to make progress with communication. Unfortunately, his ability to create art is lost as the power of language grows. After almost ten years of institutional caretaking, and with the blessings of his doctor, Roland returns to Sanford, Florida to start a journey to try to trigger what little memory he has of his former self, into a fuller understanding of what he intuitively knows he has lost.

Part of Roland’s genetic heritage is of the Seminoles, the only indigenous North American tribe to never surrender to the United States government. With Dr. Turner at his side, Roland comes to learn of his own connection to the Seminoles through Thomas Fish Hawk, a charismatic, outlaw pot farmer, and Thomas’ mother, Mary Fish Hawk. Airboat is a fiction imbued with Native American mythology, a journey of self discovery, and the redemptive nature of truth through art.

AIRBOAT

Travel across the river, its algae rich water coming up to meet you. Think of yourself on a boat now. Water hyacinths float in clumps. Small, flower laced islands whose transient archipelago stretches from one end of this Florida inland waterway to the other. You are in the middle of the state, on the St. John’s River, somewhere between Lake Monroe and Lake George.

Skip over the water. It is early morning and uncommonly calm. The St. John’s reflects the dawn. Dark glasses would hardly help.

Turn and look behind. On the bank there are mud turtles, adjusting their cold blooded systems in the sun. A rock is full of them. And there, on the protruding trunk of a lightning felled pine, are three more. They shrink in the growing distance.

Press ahead. Motion, velocity creates excitement. It rises from beneath your feet, the vibration in the fast pace. Knees bent, thighs tense to maintain balance. The wind rushes against the flesh. It will be one of those hot, oppressive Florida summer days. The air will hang on you like a sodden blanket. The type of day that seems to increase gravity.

The nearing shoreline looks fierce, primeval. Cypress roots press out of dung colored loam, gnarled fingers in a panicked grasp. Palmetto palms thrust into the air like green bayonets. A darkness lurks behind.

At the entrance to a small inlet is a ganglion of hyacinth. Throttle back. The water becomes more defined. Look close. See the current carry the water. Small contours move the surface, like tendons beneath the skin of a flexing hand. Eddies break in swirls. The water is alive, defined, not just a slate of shadow and reflected light, when speed was the thing. Slow down. Pick your way through the hyacinths. There’s a dock at hand, and a ram-shackle building. A sign above the door reads Pap’s Bait and Tackle. The letters are bold, block print, but faded into a many hued pink color. On the right corner, in the yellowed margin of the sign, is a poorly written, Marine Motor Repair. Below, a curled and crumbling cardboard sign says, Gas.

Look down, by one of the wooden posts of the dock. An alligator gar leers up at you with its awesome jaw and milky eye. Notice a gash on its back. Flesh torn away. Propeller victim.

Tie up the boat and head toward the screen door. See how it’s hung slightly askew. The boards beneath you creak. Bounce on them. Try to find their notes, their pitch and tone. A young boy used to play these boards almost like a piano. And when the dock boards would change with the weather, current, and age, the boy changed with them. He is now the nineteen-year-old welder in the backyard and work area. Around the corner of the building, you can see the young man, tall, his broad back hunched to a task. In one hand he holds a torch, in the other a brazing rod. An areola of sparks flies around him. Faint surges of the torch are heard sporadically over the lapping river.

Walk back toward the door. Draw your breath. The screen door opens with a gust of wind. Step inside as if you were this wind, unseen, but present.

Notice how your eyes did not have to adjust. Clear vision spied the movement in the corner of the room. A man at a desk turns to the opening of the door, which slams shut, rattles, then rests against the jamb. He has a long, angular face beneath the brim and shadow of his baseball hat. It’s an old Brooklyn Dodger hat. A scalloping band of sweat stains, sections white with salt, runs along parts of the brim, through the B.

He draws himself off the seat, looking like he unfolds into standing. Age is apparent in the gaunt flesh. Broad, bony angles mark the frame. Folds and crosses of wrinkled skin blossom like spider webs at the joints, the turkey neck, the ravined face.

This frozen, silent moment dissolves into the activity of flies, until the man moves forward, speaking, “Simpleton. I tell him to use the hook. Can’t ‘member none of what I tell him.” Though ungainly in his rise from the chair, the man walks to the door with a sure, efficient grace.

The old man spits a brown cud of Day’s Work into the water. He has to stoop to shove his head out the door. He stares as he spits. Upriver, downriver. Steps back inside, latches the door and strides to his desk, folding back into the chair. Bending to a sheet of paper, the man mutters, “Fish done. Bastards. Get ’em. Come out in the wash.” He grunts, sucks his teeth. In silence, his thin lips move to his thoughts. He grimaces, smiles, exposing tobacco stained teeth and bleeding gums.

You become aware of the room’s smell. Moss, cigarette smoke, something like cheese. Hear the flies again, a steady drone.

The old man jumps up, slamming his palms onto the desk. The slapping sound lingers in the ear until the man barks, “Blue birds. Stinkin’ Florida Jays.” He is staring out of the back window. The bottom sash is quartered with a cross. At the joint is peeling paint and splintered wood. The lower right-hand quarter of the window has been replaced with a piece of plywood, sealed into the frame with duct tape. The gray tape has a metallic quality, and glistens with silver sparks.

The other panes are filmed with dust, the corners of each taking on the texture of peach fuzz. The old man breathes on the pane, rubs his elbow at the center.

Look out and see the boy, the welding mask flipped back, making him look like a knight with his visor up. He’s away from the acetylene tanks, squatting on the ground near a weathered fence post that runs along the edge of the wilderness.

The boy watches two birds, both blue, one hopping actively on the top strut of the fence. The other bird is motionless, except for a cocking of its head. He brings his hand slowly toward the stationary bird, until his finger is inches from it. The bird hops onto this perch.

“Sheet,” the old man says. He bends to the window, reaching with his left hand for the eyehook latch. With a tug the hook breaks free of the ring screwed into the sill. He pushes at the wood to open the window, but it is swollen in the humidity of this day and the old man jams the heel of the hand into this bottom part of the frame. It opens with a pop. With his right arm on the desk, taking most of his weight, the old man lifts the window and shouts out, “Leave them fuckin’ jay birds go, do your goddamn work, boy!”

The birds flit away at the sound of the old man’s voice. The boy cowers, sitting back from his haunches, onto his rump. Knees come up to meet his chest, his face presses against the top of the knees, and his arms wrap around the legs.

“If’n that don’t beat all,” the old man mutters, then shouts, “Y’all dumb shit, Stump! You think I can’t see ya? Getta work!”

The boy rises without turning toward the window and goes back to the torch. Sparks begin again to fly.

The old man grunts, tries to shut the window, but it is too swollen, so he waves disgust at it, as he falls back into the chair. He draws a Lucky Strike from its package, tamps one end against the table, then places the cigarette into the corner of his mouth. In one motion he lights a match, brings the flame to the end of his cigarette, then throws the match into a butt stuffed ashtray. He eyes the thrown match with disdain as it continues to burn, stubs it out with his callused thumb.

Leaning back against the chair, whose springs sing with each bounce, the old man blows smoke into the slash of morning light. A slow, billowing, silver-webbed cloud. This stark light cuts through the window at such an angle that it points directly to the yellow, lined legal sheets on the battered desk top.

The old man’s gaze travels with his smoke into the white light and its calm suspension of dust motes. At first lost within the silver, gray billow, the dust motes swirl into sight as the smoke dissipates. Watch the old man’s eyes, the recognition of the penciled notes in the light before him.

Draw back as the old man draws near. You would not understand the scribbled notes anyway. But the old man does. See how he hunches over the work, looking like a praying mantis. Yes, you are that far back now. Up within the rafters. From this perch the man’s body is made up of insidious angles. Remember how he moved when he went to the door? Once in motion the body recaptured a remembered grace. Now, with a lack of motion to keep a balance, the body slacks and bends to the man’s inner thoughts.

And now, notice something very peculiar. The old man’s arm reaches across the desk to adjust a rearview mirror screwed to the desk and you wonder why you did not notice it before. Satisfied with his adjustment, the old man mutters, “I’ll get ya yet. I’ll get y’all.” He points his finger, jabbing at the air in front of the mirror.

But from this vantage point you cannot tell what reflection the man peers at. You want to see, but start to float upward again, through a hole in the roof, a hole once made by a squirrel the boy once befriended/tamed. A squirrel the old man shot with the l2- gauge Sheffield over a year before. Made the boy watch the killing, the skinning, and then that greasy faced meal the boy would have no part of. You perceive all this as you pass through the hole, seeing the marked wood, pocked from the scatter shot of the gun’s blast. Do not worry how you know this, but rise, rise above the roof, shingles mottled gray black from mildew, rising so the roof becomes a uniform color. See the boy now. At least the corner of him not hidden in the shadow of the lean-to work shed.

Hours pass. You can feel the crossing of the sun, its rays passing through you, the change of their angle of descent. And see, the boy’s work is revealed as the light falls into the shed, busy hands, shaving, chiseling into a block of wood. The boy works slowly, surely, like the sun, until he too reveals something. Out of the block of wood. It is a horse. You can tell, even from this far perspective, the shape of its haunch, its plumed tail.

The slamming sound of the screened door reaches up to you. The old man striding with purpose, around the building, towards the boy. The boy is lost in his work, not noticing the man’s approach until he is upon him. He tries to hide his work by covering it with his body, but is pulled away by a violent tug of his hair. The old man picks up the block of wood that is almost a horse, and turns with it in his hand. The boy backs away.

“This,” the old man shouts. The wood figure is thrown to the ground and the old man backhands the boy, who curls into a hunched, unmoving ball of flesh. The boy makes no sound you can hear, until the old man lifts a hatchet from its hidden place in the shadowed shed. The boy shouts out something that almost sounds like no, but it turns into an animal wail as the old man chops the wood into unrecognizable pieces.

Grabbing him by the hair again, the old man drags the boy across the ground between the work shed and the main building. Like a cur dog.

“Evil,” the old man says. “It the curse a that union a evil. I gotta take out the evil in ya.” He stands over the kneeling boy like a priest ready to offer the sacrament of communion. With a deft motion, the standing figure produces a belt from around his waist, showing it to the boy. The boy bends his head to the old man’s feet, in the same motion pulls his shirttails over his shoulders. The old man applies the strap to the boy’s naked back. Slowly at first, with force, the force and tempo increasing with each blow.

Feel your vision start to fade, darkness build. Sound of the belt. Increasing. Sound overwhelming sight. A void brought on by a cacophony of leather and flesh.

If you’d like to read the rest of the story, order Airboat by Dennis F. Bormann today.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.