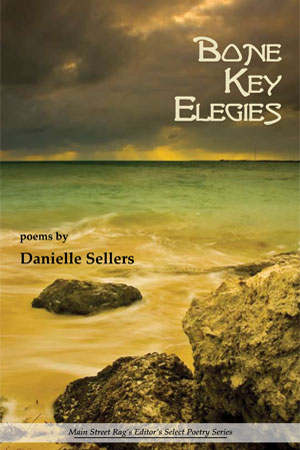

poems by

Danielle Sellers

Poetry book, 90 pages, $14 cover price

($10 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-221-7

Released: 2010

* * * This title was selected for publication as a result of finishing as a finalist in the 2009 MSR Poetry Book Award contest. * * *

Danielle Sellers is originally from Key West, FL. She has an MA from The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and an MFA from the University of Mississippi where she held the John Grisham Poetry Fellowship. Her poems have appeared in River Styx, Subtropics, Smartish Pace, The Cimarron Review, Poet Lore, Cold Mountain Review, and elsewhere. She’s founder and editor of The Country Dog Review and teaches at the University of Mississippi. She lives in Oxford, Mississippi with her daughter Olivia.

Danielle Sellers is originally from Key West, FL. She has an MA from The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and an MFA from the University of Mississippi where she held the John Grisham Poetry Fellowship. Her poems have appeared in River Styx, Subtropics, Smartish Pace, The Cimarron Review, Poet Lore, Cold Mountain Review, and elsewhere. She’s founder and editor of The Country Dog Review and teaches at the University of Mississippi. She lives in Oxford, Mississippi with her daughter Olivia.

Loss impels the eloquent poems of Danielle Sellers’s Bone Key Elegies, which commemorate their beloved dead by richly evoking specific moments in the past, in the deep history of place and of a family’s lives. “How close I came to jumping in,” she writes in the book’s last poem, of having to bid farewell to the canal “behind the house / I’ve lived in twenty years” — and Bone Key Elegies is no stranger to despair. But luckily for us all, the jumping-in takes place instead in the poems themselves, and we are privileged to experience their strange and beautiful waters.

–Ann Fisher-Wirth, Carta Marina

You can’t get farther south in America than Danielle Sellers’s moving first book. Here at Bone Key, things turn upside down. Death takes an infant sister first, before a father, a friend, a grandmother. The ocean’s allure, its creatures and aromas, empower Sellers’s poems in their fight to stave off destruction, the way her grandmother “sweeps the sea from her kitchen” after a hurricane. Sellers knows the “sheet metal dorsals” of tarpon, the “stingray, eagle ray, horse-eyed Jack,” and men transformed into “fish or fool,” swimming after women, “mouth open, kissing nothing but the sea.” Bone Key Elegies animates the brackish world at this dangerous edge of America, where everything lives close to the bone.

–Jay Rogoff

What Frost did for New England, Danielle Sellers does for the Florida Keys, shaping a world out of words that feels deeply observed, richly lived. These poems present a place where “a boy with too much muscle swirls / a soapy rag over his El Camino,” where bridge fishers sit beneath “evidence of their mis-casts / twined and dangling from power lines,” where young girls “use mangrove limbs as monkey bars” while “Navy jets scream overhead.” Shaped by and shaping this fraught landscape are the generations of a family that haunt the speaker’s efforts to feel at home, and haunt her efforts to escape: a grandfather who piloted an oil tanker, a father who could “spear a hog fish and roast it before it was dead, / squeezed lime hissing the fire down,” and a younger sister movingly eulogized after a fatal car accident. These are poems to read, and reread, and shared, and they are as beautiful, tragic, and ancient as the place they describe.

–Beth Ann Fennelly, author of Unmentionables

WINTER ELEGY

When the cool fronts gusted through

we called it Christmas.

We’d crank open all the jalousie windows

and for the rest of that year and into the next

the slamming of doors was only the wind’s rage.

It blew through our house, diffusing the seaweed

collecting at the canal’s dead end,

my mother’s cinnamon candles and pine,

sugar apples ripening on the tree,

and at night, blossoms of cacti in the corner of the yard.

Half asleep with the windows open,

I could hear the rustling of palms and bottlebrush,

blinds slapping against screens,

and at some point every night, the scream of a cat fight,

and my mother going out to break it up,

then back to bed. Through my bedroom windows

I’d hear her settle in. That overture

of sighs and low moans and my father’s constant snore

lulled me back to sleep, and I never imagined

this was not the way it would always be.

SANDBAR AT SNIPES KEY

Before the divorce, we used to picnic

on the first Sunday of each month, even in winter.

My father would belly his pontoon on the sandbar,

then my extended family swung single file

down the ladder wearing sneakers–

it was too shallow for swimming

and not all sand, but coral heads and bottles,

long-spined sea urchins, perhaps sting rays.

Arm in arm we made a chain from the boat

to shore, in flowered or fluorescent bathing suits,

like a long swatch of milky bufo eggs

to stake our claim on that small tongue of sand.

My father would carve a pit in the beach,

make fire with mangrove limbs,

spear a hog fish and roast it before it was dead,

squeezed lime hissing the fire down.

Then he’d stretch out on the sand, his arms folded

under his head like a sky-watcher.

His snore was like wave-crash. Giggling,

I poured bucketsful of sand over him.

Mixed with saltwater, it was cement.

Then I built a series of castles around him.

He’d sleep like that, pretending not to know

I was there, or was he pretending?

During one of these Sundays, our engine

broke down. And to get us home he jumped in,

pulled the pontoon by the anchor rope over his shoulder,

trudged the three bay miles to our dock.

His hands and back blistered.

That night, he stood out on the back deck

and my mother poured a bottle of peroxide over him

which fizzed like sea foam over his body.

He saw me see him wince, then exaggerated

his wincing with cartoonish eeks and acks.

He let me wind his palms with gauze.

I fell asleep with my head on his scorched chest

despite the rifle-cracks of some John Wayne movie,

both of us in his cigar-burned, soft gray La-Z-boy.

He was fond of saying, Man is greater than any misery.

Out there on the sandbar, it was easy to forget

about my parents’ last fight, the smack of his truck door.

It felt good just to dig my hands in

the muck by the shoreline, to try and bury

my father so deep in the earth he’d never leave.

AFTER HURRICANE WILMA

Sting ray planed my grandmother’s driveway,

minnows drove her Cadillac into the calla lilies.

Sand, sea weed, fish stink

flushed through every room,

seeped into the walls, warped furniture,

overturned the china carefully packed in boxes.

Like a white, long-necked ibis, flat-footed on the sandy tile

she hunts through her effects for what is salvageable

then sweeps the sea from her kitchen,

stone crabs like dust mice from under the beds.

Her housedress is damp and salt-stained.

She curls a white lock behind her ear,

wipes her brow, puts the broom in its place.

Danielle Sellers is originally from Key West, FL. She has an MA from The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and an MFA from the University of Mississippi where she held the John Grisham Poetry Fellowship. Her poems have appeared in River Styx, Subtropics, Smartish Pace, The Cimarron Review, Poet Lore, Cold Mountain Review, and elsewhere. She’s founder and editor of The Country Dog Review and teaches at the University of Mississippi. She lives in Oxford, Mississippi with her daughter Olivia.

Danielle Sellers is originally from Key West, FL. She has an MA from The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and an MFA from the University of Mississippi where she held the John Grisham Poetry Fellowship. Her poems have appeared in River Styx, Subtropics, Smartish Pace, The Cimarron Review, Poet Lore, Cold Mountain Review, and elsewhere. She’s founder and editor of The Country Dog Review and teaches at the University of Mississippi. She lives in Oxford, Mississippi with her daughter Olivia.