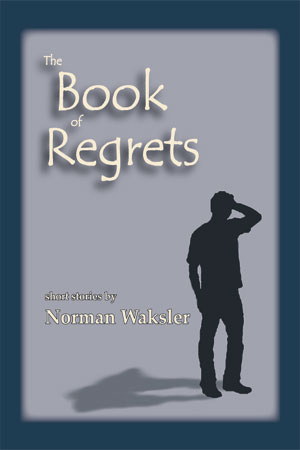

Short Fiction by

Norman Waksler

Poetry book, 195 pages, $8 cover price

OUT OF PRINT

ISBN: 978-1-93090-789-8

Released: 2005

Mr. Waksler was a runner up in the 2004 MSR Short Fiction Contest. His story, “The Pain,” will also appear in the 2005 MSR Short Fiction Anthology.

Norman Waksler, raised in Providence, RI, moved to Boston for college, and remained in the area. He has worked at the various writerly jobs—taxi driver, warehouseman, bookseller, janitor, school teacher, magazine distributor, camp director, salesclerk, and most recently, and for many years, librarian. His short fiction has appeared in in such places as Ascent, Kansas Quarterly, Greensboro Review, Hanging Loose, StoryQuarterly, Madison Review, Chaffin Journal, and Bibiophilos, as well as in Best American Short Stories. He was the recipient of a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship in Ficton for 1998. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his sociologist wife Frances Chaput Waksler, and a small menagerie of not very exotic animals.

Norman Waksler, raised in Providence, RI, moved to Boston for college, and remained in the area. He has worked at the various writerly jobs—taxi driver, warehouseman, bookseller, janitor, school teacher, magazine distributor, camp director, salesclerk, and most recently, and for many years, librarian. His short fiction has appeared in in such places as Ascent, Kansas Quarterly, Greensboro Review, Hanging Loose, StoryQuarterly, Madison Review, Chaffin Journal, and Bibiophilos, as well as in Best American Short Stories. He was the recipient of a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship in Ficton for 1998. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his sociologist wife Frances Chaput Waksler, and a small menagerie of not very exotic animals.

Charley Regrets

The way Charley Cohen saw it, his long friendship with Dan Giles was creaking slowly to an end, like a tired old dog taking its last steps before lying down and giving a final arthritic wag. They’d met as college sophomores thirty-five years ago, discovered a mutual interest in the English novel, ‘creative’ writing and low key irony, gone to separate, distant grad schools and met up again in the Boston area, where Charley became an urban librarian, Dan an ex-urban high school teacher. Charley figured they had probably seen each other every two weeks the next few years, an average only slightly affected when Dan married Marlene. They’d continued to get together regularly; often Marlene made dinner for Charley, or for him and his inamorata of the minute; sometimes the pair came to his apartment in Carbury, although after their first child it became more convenient and habitual for him to drive out to Westford.

They went to movies at times, plays occasionally, but the staple of their friendship was talk, mostly about books, mostly about fiction. Over the years Charley and Dan had read similarly, including vast quantities of Anthony Trollope, while Marlene, a Comp Lit major who’d learned accounting so she could work part time while raising children, was a devotee of Dickens, Proust and Thomas Mann. Their evenings together were generally spent on fat chairs, a cup of something hot nearby in cool months, a glass of cool in hot, as they analyzed, opined, recommended and argued, sometimes with Charley’s dog of the decade a permitted guest at his feet. It all fit closely and comfortably with the notion Charley had come across in Sallust, that to like and dislike the same things was what constituted true friendship.

But recently, perhaps the last three years, a hitch had developed in the easy stride of their rapport, which developed into an irregular stumble, and finally became this almost moribund stagger. Looking back, Charley could never locate a particular incident that might have set off the decline. Sure there had been strains in the friendship; all friendships have strains that need to be accommodated. In their triad, Dan was always a bit testy, Marlene had a tendency toward snideness and inflexibility, he himself could be self-absorbed and arrogant; they all liked their own way. Perhaps he’d changed unawares, or had unconsciously expressed contempt for their quiet ex-urban life (though every few years they went to Europe while he stayed stuck in Carbury), or they’d changed in ways he couldn’t see, or they’d come to disapprove of his bachelor life. Certainly, the three of them couldn’t have tripped over that old literary chestnut, inherent antagonism between city and town. In any case, there had never been an egregious collapse of the means by which they reconciled their differences and failings of temperament.

However, he could remember an incident which time-stamped the change. Dan and Marlene had stopped smoking years before. “So our kids’ll get jobs after college and develop their characters instead of living off our life insurance,” said Dan.

Charley had continued to smoke the stumpy Dutch cigars he’d been enjoying since just after college, in the same moderate quantity, four or five a day. The time he was thinking of, Marlene had confronted him before he’d had a chance to light up after dinner, when Dan was off in the bathroom. “You know, Charley,” she said. “We’d appreciate it if you wouldn’t smoke in the house any more. The smell hangs in the curtains for a week, and it gets into the rugs. You should probably quit, anyway. What with your weight, they’re probably heading you straight toward a heart attack.”

Charley hadn’t minded her request: she was house proud and not the first to ask; and he’d been only mildly affronted by the reference to his weight; but there had been an impatience in her asking, as if she resented having to bring it up and he should have thought of it himself, and a hardness more suitable for repulsing inappropriate strangers.

It had seemed a momentary break in the long line of their cordiality, but after that came a series of stings and nips from both of them: failure to recognize a witticism, offhand dismissal of ideas, a snide remark about a previous woman friend, ridicule for a literary misjudgment, refusal of an invitation to his apartment, turned condo, for dinner, more frequent comments about his weight and physical condition. Then comments he made which might once have been viewed as humorous and innocent were taken wrong and found offensive. Instead of acquiescing in his latest romantic illusion, they tried to represent it to him realistically, showing how it had all the characteristics of earlier brief and failed affairs, not to mention wasn’t he a bit old and wasn’t it a bit ridiculous for a man his age to be seeking and thinking he’d found romance? Dan and Marlene canceled engagements more frequently, more time passed between get-togethers in general. And where once if he disagreed with them, about a book or a writer or a literary movement, the argument would have been unemphatic, self-deprecating, temperate, yielding, now all three of them insisted, stressed certain important and irrefutable words and phrases, were formal and rigid, exited each argument without shaking hands.

Norman Waksler, raised in Providence, RI, moved to Boston for college, and remained in the area. He has worked at the various writerly jobs—taxi driver, warehouseman, bookseller, janitor, school teacher, magazine distributor, camp director, salesclerk, and most recently, and for many years, librarian. His short fiction has appeared in in such places as Ascent, Kansas Quarterly, Greensboro Review, Hanging Loose, StoryQuarterly, Madison Review, Chaffin Journal, and Bibiophilos, as well as in Best American Short Stories. He was the recipient of a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship in Ficton for 1998. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his sociologist wife Frances Chaput Waksler, and a small menagerie of not very exotic animals.

Norman Waksler, raised in Providence, RI, moved to Boston for college, and remained in the area. He has worked at the various writerly jobs—taxi driver, warehouseman, bookseller, janitor, school teacher, magazine distributor, camp director, salesclerk, and most recently, and for many years, librarian. His short fiction has appeared in in such places as Ascent, Kansas Quarterly, Greensboro Review, Hanging Loose, StoryQuarterly, Madison Review, Chaffin Journal, and Bibiophilos, as well as in Best American Short Stories. He was the recipient of a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship in Ficton for 1998. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his sociologist wife Frances Chaput Waksler, and a small menagerie of not very exotic animals.