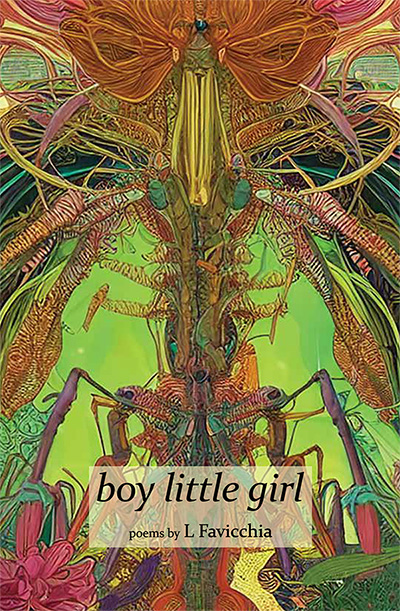

boy little girl

poetry by

L Favicchia

~96 pages, $15 (+ shipping)

Release Date: June 9, 2023

The Advance Sale Discount price on this title is no longer available. For those who prefer to pay by check, price is $19/book (which includes shipping) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, PO BOX 690100, Charlotte, NC 28227-7001.

L Favicchia is a poet, writer, and teacher living in Kansas where they are finishing their PhD in creative writing. They have been nominated for Best of the Net and Best New Poets and were a finalist in the 2018 Ryan R. Gibbs Award for Flash Fiction and the 2021 Meridian Editor’s Prize in Poetry and Prose. Their work has been published in many literary journals, including Post Road, Permafrost, The Normal School, Okay Donkey, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry. Additional information and publications can be found at lfavicchia.com.

L Favicchia is a poet, writer, and teacher living in Kansas where they are finishing their PhD in creative writing. They have been nominated for Best of the Net and Best New Poets and were a finalist in the 2018 Ryan R. Gibbs Award for Flash Fiction and the 2021 Meridian Editor’s Prize in Poetry and Prose. Their work has been published in many literary journals, including Post Road, Permafrost, The Normal School, Okay Donkey, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry. Additional information and publications can be found at lfavicchia.com.

The poems in boy little girl show that even when beings die, they remain. Favicchia accomplishes something that is both captivating and heartbreaking with these intricate poems; they ask readers why it needs to hurt so much when we are described beyond the naked eye. I think they tell us that the fullness of the world hitting us back will always be worth it for the people we become. ~Ginger Ko

boy little girl, is an imaginative act of rebirth and rebodying, a studied disappearing from the always emergency of a troubled home into wonder for and of the more-than-human world. The poems form an interspecies coming-of-age story where fear and longing collide with curiosity and care for the tender monsters of the wetlands and of the chronically ill body. Childhood explorations in a drained swamp become teachers, countering learned familial violence toward othered bodies and beings. ~Megan Kaminski

The speaker of boy little girl digs into beetle-packed soil, frog-strewn marsh, the split gills of memory, and the animal body. Is there anything more simultaneously mysterious and intimate than one’s own interior, submerged and untouchable? Through a scrim of blood, moss, and curiosity, our speaker finds themselves an inside-outer in a world full of right-side-outs, and wonders aloud if, here on earth, “it’s best […] to try to appear more orchid than exoskeleton.” ~Danielle Pafunda, Author of Spite

The Orchid Mantis’s Body is Not Straightforward

It’s best to be born pink, to shake

while you walk, to braid everything,

to try to appear more orchid

than exoskeleton. It’s best to be born

small enough to wade

through tall, light grasses

of arm hair. If you will more pink

into your capillaries and nibble tupelo,

lick it from where you’ve stepped, it’s easier

to pretend you don’t have sickle feet,

though you must still try

not to split your tongue.

A menagerie of small insects

may eventually quiet your fear of holes,

no longer plunging into yourself

to return with shoulders no sharper.

You scare your neighbors

by standing perfectly still—

you were born pink

but didn’t stay that way,

you were born small

and still are.

The Females of Some Species Are Larger

My instinct is not to bite.

Instead I’ll show you all

my little square teeth,

point them out to you

one by one name them

then leave my mouth open

and breathe.

Enamel speaks a thing you can’t

understand—the grain of sand

churning in the oyster

who layers thick saliva

over and over until pearl

to numb the gnawing and is still

left with a tender lump inside—

one she is torn apart for.

Why isn’t the female larger

and more colorful? Give me the terrified

red veins of the albino raven,

the deep flush and large forearms

of the orchid mantis, also afraid.

Let me have fiery long hair that stings

with the smell of burning oak.

When I skin myself, I skin myself

in front of a mirror to see

all that pretty muscle.

I rehearse what crying looks like,

in my wardrobe keep buttons

that close soft bobbled sweaters

and feel an increasing desire

to become mud, to lie

beneath leaf litter and hide

from grabbing hands

that would put themselves inside me,

playing dead to save myself

from the salt of their fingertips

that craves a wound.

(i have nothing to offer)

i. my grandmother’s cookbook

there needs to be more

oregano. oregano

in everything, blood

oregano. oregano blood.

pickled turnips

are a red meal

like blood matted

in the damp hay of her hair

and your fingerprints

stained pink from beets,

the artificial color you wash away

in handfuls of untamed duckweed.

ii. my grandmother’s cookbook

i have ash on my legs,

my legs that have too many ankles.

i hold a tissue paper body

as long as i can,

or until i must exhale.

she was beautiful

and then she died

and was still beautiful.

have you ever excused yourself

to an empty room

just to whisper oregano?

Self-Portrait as a Glass Doll

After Anne Sexton and Nancy Reddy

Snow White was ten and knew something

was wrong, pale-faced and glass-eyed

as her companions tried to stir her.

She was bleeding inside

and out of season. There is no evil

stepmother, but doctors

said she sought ruby-lipped attention. She pretended

she was asleep when her father came

to mock her for growing

breasts. She shut her eyes tightly

wishing away the glass dome

as darkly as her own insides.

She was on Depo Lupron—

a drug not meant for anyone

under eighteen, made to induce menopause

in patients much older than her,

the crone, the witch, she became

her own daughter ouroborosed.

She vomited into bushes

as black tissue blotted stray organs,

mistaking them for infants

meant to be swaddled, very confused uterus

blooming inside with endometrium,

the too-comforting terrarium of her gut.

She thinks her doctor was disappointed

to find the little tufts,

her confettied bladder and intestines,

and so took her hymen,

cut it roughly away while she slept,

body never safe

from gloved hands. Daily she wakes

back into gender, no prince

but salted fingertips

dipping themselves inside

her glass-domed body

always surprised to find a tight bundle

of scar tissue as they ask her, sleepless,

if she knew these practices

were antiquated and barbaric.

L Favicchia is a poet, writer, and teacher living in Kansas where they are finishing their PhD in creative writing. They have been nominated for Best of the Net and Best New Poets and were a finalist in the 2018 Ryan R. Gibbs Award for Flash Fiction and the 2021 Meridian Editor’s Prize in Poetry and Prose. Their work has been published in many literary journals, including Post Road, Permafrost, The Normal School, Okay Donkey, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry. Additional information and publications can be found at lfavicchia.com.

L Favicchia is a poet, writer, and teacher living in Kansas where they are finishing their PhD in creative writing. They have been nominated for Best of the Net and Best New Poets and were a finalist in the 2018 Ryan R. Gibbs Award for Flash Fiction and the 2021 Meridian Editor’s Prize in Poetry and Prose. Their work has been published in many literary journals, including Post Road, Permafrost, The Normal School, Okay Donkey, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry. Additional information and publications can be found at lfavicchia.com.