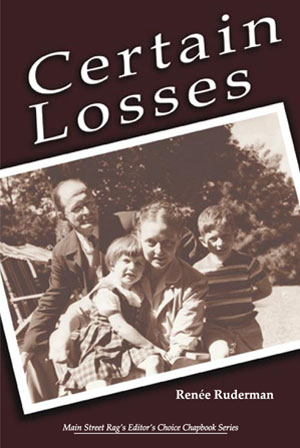

poems by

Renée Ruderman

Poetry chapbook, 36 pages, $7 cover price

($5 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-93090-760-7

Released: 2004

This title was selected for publication as a result of finishing as a runner up in the 2004 MSR Chapbook Contest.

The poem, “Leaving Furth bei Nuremburg, 1936,” included in this collection, won first prize in the New Millenium Writings poetry contest in November 2004.

Renée Ruderman, born in New York City, is an assistant professor of creative writing at Metropolitan State College of Denver. Her first poetry collection, Poems from the Rooms Below, was published in 1995 by Permanence Press, San Diego. She has won national prizes for her poems, and some of them have appeared in The Bellingham Review, Xanadu, Eclipse, Buckle &, and New Millennium Writings. Renée has been a Writer in Residence at the Vermont Studio Center (1997) and The Woodstock Guild (1999).

Renée Ruderman, born in New York City, is an assistant professor of creative writing at Metropolitan State College of Denver. Her first poetry collection, Poems from the Rooms Below, was published in 1995 by Permanence Press, San Diego. She has won national prizes for her poems, and some of them have appeared in The Bellingham Review, Xanadu, Eclipse, Buckle &, and New Millennium Writings. Renée has been a Writer in Residence at the Vermont Studio Center (1997) and The Woodstock Guild (1999).

GIFT

This box passed down by her mother

with an eye for good wood,

inlaid with a mountain village,

houses with windows like electric sockets.

Part of a wall marches on the right;

a mountain peak cuts darkly, and six birds

in drooping wings hang above the treeless

town which has no steeple..

She shakes the locked box, hears its key inside.

She thinks this box,

its wood stolen from a Polish grove,

contains a crumbling yellow star

with pinholes like tiny scabs.

Now and then she picks it up,

knows this is what she’ll do,

all that she can offer:

listen to the key’s clatter,

then the shush of cloth.

THE WEIGHT OF WINTER

In an oil painting of Dutch rooftops in The Hague,

no faces fade in any of the twenty-three darkening windows.

The houses are not abandoned, though it’s war-time.

The roofs slope so steeply, only a thin layer of snow remains,

and the sky hangs in green diffuse light; it might snow again.

The dormers in the roof are the only joy thrusting out from

the narrow slabs of buildings; otherwise the scene sinks and wants

to curl in on itself, like a burning paper. A street must lie below,

but from this angle I hear no footsteps or the opening of a door.

Who lives and stays inside is gaunt, ducking under the

isosceles triangle of the attic. The chimneys are cigars

dusting ashes into the sky. I know my grandmother hid

on this street, wearing black, not looking down.

The Women with Accents

I should have listened to them

dressed in their German accents

and stockinged, husky legs.

I would have heard their songs

about reading to absorb the night,

how the wind whisked their coats

open on New York City’s dark corners.

They were grateful for my mother’s invitations;

came out on the train, breathed in green hills,

but they were never too hungry,

lifting forks slowly, curving their words

over goulash, smiling at me like hands

taking me where I did not want to go.

Yes, I have a boyfriend, I told her.

Nicht du! she shook her head,

tucking it into her neck.

They admired my youth

and combed it into my vanity.

I forgot to ask, What did you have

to leave behind? and

What happened to your husband?

I edged toward the door;

drove top-down, cross-town.

Renée Ruderman, born in New York City, is an assistant professor of creative writing at Metropolitan State College of Denver. Her first poetry collection, Poems from the Rooms Below, was published in 1995 by Permanence Press, San Diego. She has won national prizes for her poems, and some of them have appeared in The Bellingham Review, Xanadu, Eclipse, Buckle &, and New Millennium Writings. Renée has been a Writer in Residence at the Vermont Studio Center (1997) and The Woodstock Guild (1999).

Renée Ruderman, born in New York City, is an assistant professor of creative writing at Metropolitan State College of Denver. Her first poetry collection, Poems from the Rooms Below, was published in 1995 by Permanence Press, San Diego. She has won national prizes for her poems, and some of them have appeared in The Bellingham Review, Xanadu, Eclipse, Buckle &, and New Millennium Writings. Renée has been a Writer in Residence at the Vermont Studio Center (1997) and The Woodstock Guild (1999).