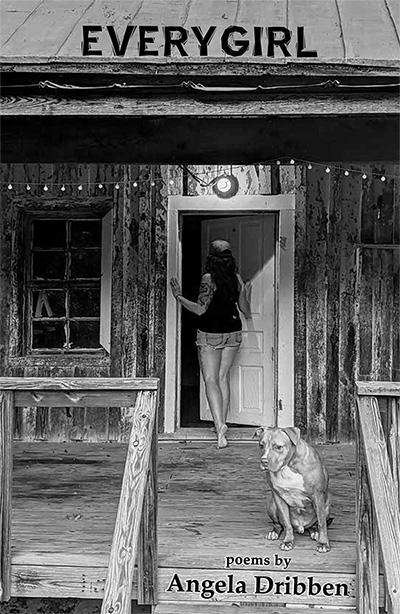

Everygirl

poems by

Angela Dribben

ISBN: 978-1-59948-862-2, 80 pages, $14 (+ shipping)

Release/Ship Date: May 4, 2021

The Advance Sale Discount has expired. For those who prefer to pay by check, the price is $18/book (which includes shipping + applicable sales tax) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, PO BOX 690100, Charlotte, NC 28227-7001.

After 22 years as a massage therapist, Angela Dribben’s scoliotic spine gave her reason to retire and turn to writing. She found herself at Bread Loaf a few months later. From there her work made its way into journals such as Crab Creek Review, Cider Press Review, San Pedro River Review, and Crack the Spine. In February 2020, the week the pandemic struck the US, she brought her husband and dog home to Southside Virginia, pursuing her lifelong passion of swallowing seeds to see if she can grow a melon right from her navel.

After 22 years as a massage therapist, Angela Dribben’s scoliotic spine gave her reason to retire and turn to writing. She found herself at Bread Loaf a few months later. From there her work made its way into journals such as Crab Creek Review, Cider Press Review, San Pedro River Review, and Crack the Spine. In February 2020, the week the pandemic struck the US, she brought her husband and dog home to Southside Virginia, pursuing her lifelong passion of swallowing seeds to see if she can grow a melon right from her navel.

“How can I believe Adam/ came first when the flower precedes the fruit?” Angela Dribben writes in Everygirl. Coming of age in a Virginia of hunting dogs, pick-ups, and hog farms, these poems, evocative in their details of men “smelling like labor,” food, such as gelatinous ham, military school life for young women, menstruation, rape, and including occasional photographs, bluntly acknowledge the destructive impact of male prerogative when social class and rural life leave few ways out. ~Susana H. Case, author of Dead Shark on the N Train and Drugstore Blue

Wordsworth wrote that any great writer must create the new taste by which they’ll be enjoyed. In Everygirl, Angela Dribben doesn’t just offer a new taste, she’s created an entire menu. From tragically vivid poems about surviving military school, to surreal poems exploring belonging, Dribben had me eating out of the palm of her hand. Dribben writes “To love and to see are not the same,” and I agree. But I do both love and see this book. ~Paige Lewis

Where I’m from

There are men

who hunt with dogs

who bark the sound of privilege.

There are men here who

train their dogs to hunt

fox who cannot get free of the fence.

These men perch in pulpits and pews

and on a Ranger bass boat seat pedastaled

atop a dog cage in the back of a Chevy pick-up,

rifle across lap. Chauffeured to prey.

These men hide from their wives

in a cabin they call hunting

with buddies they call club.

Roost in the couches yellowed

from time and dust against the back wall.

Alternate VHS tapes of Tombstone and Lonesome

Dove. Drunk on Bud Light, lost in hero dreams starring themselves

as Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday, Robert Duvall, Tommy Lee Jones.

Flip caps out the broken window they don’t plan to repair.

A cricket fries beneath a lens

popped out of a cheap pair of glasses

during an every-Saturday debate

over who has the biggest rack.

Hardest fist wins

or is it biggest

They pin a poster of a Vanity Fair panties model

all feathered hair and eyeshadow

just behind the butcher stand.

Imagine them, sharp knives

slicing through the fascia

with skill and delight.

Separating skin from muscle.

Confusing the rise from the poster

with the rise from the knife.

There are men here

who know women

aren’t good for much

except repeating their mother’s pecan pie recipe

or keeping the volume just right on the sound system

ensuring the congregation doesn’t miss a syllable of the sermon.

There are men

here who know young girls

are the easiest

to hoist by their cut offs and tank top and tan

onto the deep freeze on the screened back porch

while their wives shop for nuts.

Like me, who believed

I would become his wife in an afternoon.

When I still though his farmhouse and its tobacco fields—

two stories and flowering poison—

the air feeling like sparklers and soft grass

was something worth wanting.

The Order of Things

Momma’s mantra for her sixties, I am not responsible

for anything I did before forty, explained her straightfacedness

when she poked out her bottom lip on behalf of my brother-in-law’s

unseen scars, Bless, I don’t know how anyone could beat their children.

This moment always comes with her, my Milky Way, stars and darkness,

swallowed by microbursts of remembrance, of flying furniture, of flying

off the back porch, of the door to my bedroom slamming against me,

against the wall behind me, over and over because I painted the window trim

gloss black with the paint she brought me. Because I ate more gelatinous packaged ham slices

than she had accounted for, failed to run dish water hot enough to burn, or when I did

I used her latex gloves to survive scalding temperatures meant to destroy bacteria, sin, and skin, those gloves belonged to her. These offenses sunk her skin in around her skeleton, glazed

solid black pits for eyes, sent limbs spinning through the living room. Tasmania.

I raked her silver Caprice Classic down the brick wall, wheel well to wheel well.

Steppenwolf turned up until I couldn’t hear the metal grind. She only rolled her eyes.

When I was in high school, she drank screwdrivers with my girlfriends on Sundays

while I cured all their hangovers with bacon. The order of things

preoccupied her, not my moral fallibility, fucking my best friend’s boyfriend

at sixteen while Momma folded laundry with precision in the next room. Seam to seam.

Sleeve to sleeve. Tightly creased. Wash the mug where your mouth goes first,

then the inside, the outside and the handle. Clean house every Saturday morning at 7am

after coffee, after aerobics, before grocery shopping at Food Lion, from ceiling down

to baseboards. The bathroom last, toilet after sink, after bathtub, before floor. Order

to be preserved or punishment to be persevered. Thirty years pass, I find all houses filthy

but Momma’s, keep my own husband close by my side, incessantly backstitch

threads of culpability into my memory. It creates a very strong seam.

Every Girl is Someone’s Daughter

Petite, thirteen, I fit in his

Quartermaster-issued laundry bag.

A postgraduate football player, broad shouldered,

he’d throw me over one, haul me

up to his bed in the barracks.

I’d play dead, say nothing.

That’s what girls do,

speak when spoken to.

When he was done with me he’d grin,

a thin grin in a wide head of blonde curls.

I hate blondes.

I’d get back into his bag,

dirty laundry.

Years later, when someone says,

Kevin asked about you,

wondered if you’re still that crazy girl.

I imagine him imagining his daughter,

now thirteen, as a stained t-shirt

in a defensive back’s laundry basket,

his face fading to frown.

Boys Will Be Boys

Mine is still a man’s world,

after military school, boys to girls, 30 to 1,

after United States Air Force on an all-male pest control crew,

even at a woman’s college,

it’s still a man’s world.

I watch him lecturing in front

of my African Politics class.

Half-way across the expansive white board

his nervous system holds muscles hostage.

I choke on compassion for I know

what it is to have your body betray you.

Frozen in front of us. Unable

to move forward,

even he sees me as prey.

Weak. Or like he’d have me believe, gifted

enough to be his Research Assistant.

Parkinson’s stuttering against his body,

he offers opportunity to be titled

in exchange for a little special attention.

I like you, he says, I want to spend time with you.

Within bricks shaped, stacked and

mortared to educate the minds of women,

there is still a man at the front of my class.

After 22 years as a massage therapist, Angela Dribben’s scoliotic spine gave her reason to retire and turn to writing. She found herself at Bread Loaf a few months later. From there her work made its way into journals such as Crab Creek Review, Cider Press Review, San Pedro River Review, and Crack the Spine. In February 2020, the week the pandemic struck the US, she brought her husband and dog home to Southside Virginia, pursuing her lifelong passion of swallowing seeds to see if she can grow a melon right from her navel.

After 22 years as a massage therapist, Angela Dribben’s scoliotic spine gave her reason to retire and turn to writing. She found herself at Bread Loaf a few months later. From there her work made its way into journals such as Crab Creek Review, Cider Press Review, San Pedro River Review, and Crack the Spine. In February 2020, the week the pandemic struck the US, she brought her husband and dog home to Southside Virginia, pursuing her lifelong passion of swallowing seeds to see if she can grow a melon right from her navel.