A Novella by

A. Rooney

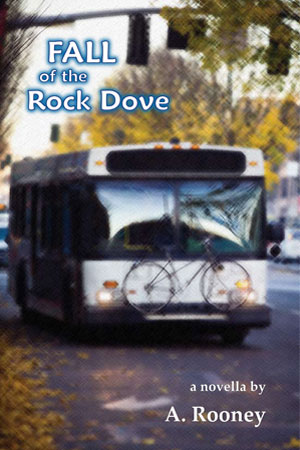

112 pages, Cover price: $11

ISBN: 978-1-59948-373-3

Released: 2012

Synopsis

Fall of the Rock Dove, a novella in nine chapters, tells the story of a loveable sad sack Hollis Hanfre, who endures the absurd Disability Office and Mr. Weed, and is joined by the handless Bonifacio, the blind Trevino, and his new-love Janet. He goes to the Disability Office because of his damaged feet and seeks solace later from his friends, like James and Percy, at the Eighth Avenue Bar and Grill.

This duck-footed mathophile finds love as well as his demise in a relationship with a woman-thief who has stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars from pop machines all over the city. It’s a star-crossed ride for one unfortunate protagonist, and his quick sexual evolution. In the end, his life takes a permanent-and unfortunate-turn when he has an encounter with a police detective in a Laundromat. Hollis mans up and takes the rap for sweetie-pie, but that may mean time in the big house.

A. Rooney

A. Rooney

A. Rooney currently teaches graduate creative writing at Regis University in Denver. He is the author of three novels; The Fact of Suffering, based on his time in Nigeria, The Dictionary of Finds, a travel word-play novel that uses Webster’s original dictionary and The Moirologist in Passing, about a protagonist who becomes a keener for others and himself. He is also the author of a collection of stories, The Colorado Motet, published in 2005. Travels in Ekphrasia, a collaborative art/writing chapbook, was published in 2006. A. Rooney has worked on the railroad, in a slaughterhouse, as a bus driver, in a big loser corporation, and on newspapers and magazines. His short stories and some of his poetry have appeared in journals, magazines, anthologies, and collections, and they have won prizes, although not any really big ones. He is the father of Gabe and Kelsy and the grandfather of beautiful Sofi.

Fall of the Rock Dove exhibits a marvelous range of characters. With humor that ranges from deadpan to outrageous, Rooney guides us through lifestyles that both delight and intrigue. Rooney’s people drop the cruise-control option while they navigate their own unpredictable journeys. Fall of the Rock Doveintroduces us to a new world.

Keith Abbott,

author of Downstream from Troutfishing in America:

A Memoir of Richard Brautigan and Racer: Collected Stories

A terriffic journey into the blind alleys of the human soul. Fall of the Rock Dove is dark and rich and very funny, full of vivid characters and fevered tales.

William Heywood Henderson,

author of Native, The Rest of the Earth, and Augusta Locke

A. Rooney’s masterful fiction is honest, down-home, and as quirky as the weather. Spend an evening with these characters and you’ll feel like you’ve known them all your life.

Erika Krouse,

author of Come Up and See Me Sometime.

Once I was out in the field on a hail disaster in Minnesota, no, Wisconsin, over near Janesville. Banged up all their wheat, put holes in roofs, broke windshields, even killed livestock. That was something. This was a hundred-million-dollar claim. We’re sitting in a little restaurant early, early, and somebody introduces me to this Swedish farmer. He sits down in the chair next to me, shakes my hand and tells me “Your face looks so simple I think I should know you.” He didn’t really mean it to be funny, he thought maybe I was a distant relative or an old neighbor, but the other adjusters got a hardy-har over that.

The truth is my face does look simple, and the rest of me is kind of simple too. I’m not very funny, I’m not good with the ladies, I don’t play any instruments, I’m uncoordinated, I don’t drive, I don’t own any property, and on top of all that I have duck feet. Except for math, I don’t know that I have much in the way of redeeming qualities. I am simple, the Swedish farmer was right.

I play a game with myself while I watch for the bus or when I wait at the stop: How close can I come to guessing the block number, the type of bus, and the actual number of the bus, not the route number, all combined. See, buses don’t just come out of the barn like wild horses, there’s an enormous arithmetic, a linear algorithm. The northbound could be a Gillig, for instance, and the actual number of the coach might be 8048. Now if it’s the first bus on the route at five a.m., the block might be 101 and the bus that leaves thirty minutes later would be 102. And then I add up the numbers and guess what the total’s going to be, like the #65 bus that was coach 8048 and block 101, which comes to 8214, and if I get the addition right I can go wherever I want for lunch or dinner, or whatever the meal is. I can go wherever I want anyway, within limits, but it’s just a game I like to play.

You’d think I’d hate buses after my accident, but I don’t. In second grade I stayed on the school bus till it got back to the garage, and the driver had to give me a ride home. I felt like a king or a little prince then in that big coach, and I loved that feeling so much. Maybe I just have a thing for buses, like the retarded boy with the grocery ads.

At times I just want to slap myself, pretend I’m James and shout “Hollis, Hollis.” But when I talk I feel kind of connected, to myself and to other people, and like I’m part of the story, somehow. Maybe my talking fills me up, too, because I’m a little afraid that if I look inside there won’t be anything.

“What’re you going to do, Hollis, keep on with your poor-ass self forever? You’re going to be an old man all alone and they’re going to come find you after a week in front of your newspaper, dead, TV on in the background, and your cold cup of decaf sitting on the counter. Be thankful some pretty girl wants to lay down with you, give you a little loving, take care of that white body. In Africa when male elephants separate themselves from the herd they get strange, they forget how to act, start tearing things up, and eventually either the villagers or the government has to go out and shoot them. Better to be with a woman, Hollis, even if it means a little trouble. You don’t want to separate yourself.”

While I was nodding off on the sofa after Percy gave me a ride, I saw Janet and me on Italian scooters in downtown Denver and she had a scarf around her head and sunglasses. Part of the time she was on the back of mine and part of the time she drove her own. We were driving too fast, something I would never do, but it was so much fun and we weaved in and out of traffic. People in the cars and on the sidewalks shouted our names, “Hey, Hollis, hey, Janet,” and we waved to them but never stopped. Somewhere along the way I saw Topley and the kids and they called out for her, but she either didn’t hear them or was ignoring them. We parked in front of my apartment building and Janet smiled a big smile with red lipstick and we went upstairs.

Except for a man reading the newspaper at the far end, there is no one in the laundry. I unlock the pop machine quickly and begin emptying the change into the canvas bag. My hands shake a little because this is my first actual time. The man with the newspaper comes and asks if I have change for a twenty, the changer won’t take large bills. Yes, I tell him, and count out ten and then ten more stacks of four quarters.

“In a few minutes I’m going to have to cuff you, Mr. Hanfre, and take that money and put you in the car,” he says, “but in the meantime I wonder if you’d share with me why you ever got into this line of work, what prompted a fella like yourself to indulge in this sort of criminal behavior?”

“I see this pretty often,” he says, “a man will get separated from all of his relations, lose track of friends, and not be able to figure out how to be in society. He’ll make bad decisions and his vision of where he’s going will become unclear. Not real criminals, not mad dogs or bad people, but they’ve somehow crossed the line and in our society we can’t allow that.”

I see women driving and smoking and checking their makeup, men holding their arms out the windows of their cars, tapping on the roof, pedestrians deciding whether to cross against the light, teenagers at a retail counter looking up as we pass, the sunlight moving through the windows and reflecting off glass and chrome. It wasn’t really me all those times, I want to say to him, it wasn’t me. It was her, I just went along with it until this last one. I opened this one but none of the others. No words rise in my throat, though, and then the detective speaks again.

What I’m doing, what am I doing? How would the elephant in the jungle act, what would he do now? I don’t think I’m the kind of person who should go to jail, even though I have a tattoo. I didn’t even, I didn’t get any of the money, none. Ask Janet, I mean….

Anyway, it might be for the better, being in jail, because at least I’ll have a regular schedule and people around and Janet will more than likely go home to the kids, if Topley will take her. It probably will be a lot to take on. But who knows, maybe jail will turn out to be a six-eight-six. Or a five-nine-five. Guess I’m getting ready to find out.

If you would like to read more of Fall of the Rock Dove by A. Rooney, order your copy today.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.