stories by

Steve Cushman

300 pages, $14.95 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-146-3

$14.95

Out of stock

stories by

Steve Cushman

300 pages, $14.95 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-146-3

Steve Cushman was born in Massachusetts and grew up in Florida. He earned an undergraduate degree at the University of Central Florida, then an M.A. from Hollins University and his M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. His debut novel, Portisville, was the winner of the 2004 Novello Literary Award. His stories have been published in the North American Review, 100% Pure Florida Fiction, Rosebud, Village Rambler, and the Raleigh News & Observer, among others. For the last fifteen years, Steve has worked as an X-ray Technologist and is currently employed at Moses Cone Memorial Hospital. He lives in Greensboro, North Carolina with his wife and son.

Steve Cushman was born in Massachusetts and grew up in Florida. He earned an undergraduate degree at the University of Central Florida, then an M.A. from Hollins University and his M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. His debut novel, Portisville, was the winner of the 2004 Novello Literary Award. His stories have been published in the North American Review, 100% Pure Florida Fiction, Rosebud, Village Rambler, and the Raleigh News & Observer, among others. For the last fifteen years, Steve has worked as an X-ray Technologist and is currently employed at Moses Cone Memorial Hospital. He lives in Greensboro, North Carolina with his wife and son.

“Steve Cushman has written a bittersweet valentine to the luckless, the ordinary people Bob Dylan described as confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones and worse. Set in the American South, these stories don’t dwell on characters’ misfortunes; humor and heart bring them moments of insight and grace. A wonderful new collection.”

–Susan Hubbard

author of The Society of S

“Steve Cushman writes bravely, unafraid to take his characters right up to the brink. In Fracture City, a riveting, heartfelt collection, Cushman explores desperation and all the surprising, selfish and even compassionate directions it can lead us.”

–Tommy Hays

author of The Pleasure Was Mine

“The characters in Steve Cushman’s excellent stories occupy a precinct adjacent to the neighborhoods of Larry Brown and Raymond Carver. Like the characters of those writers, these people are fighting–if sometimes losing–the good fight: They want to feel more, and they want it to last. Reading these honest and effective stories, you’ll feel more than you bargained for, and those feelings will last long after you close the cover.”

–Michael Parker

author of If You Want Me to Stay

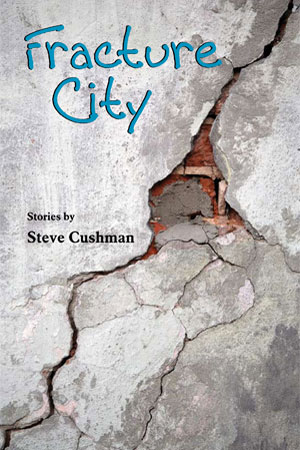

Fracture City

I wasn’t normally a smoker but that night when Rothco, the ER charge nurse, walked outside and offered me a cigarette I gladly took it. I had just X-ray’d my first dead person, a twelve-year-old kid with a thin line of peach fuzz across his upper lip. We didn’t normally have to X-ray dead people, but the morgues’ machine was broken so they’d called and asked if we’d shoot some films, see if he had any fractures to go along with the bleeding in his brain that had actually killed him. The story I’d heard was that he’d been walking home when a car hit him. What he was doing on the side of the road in the dark didn’t seem to matter.

After finishing the X-rays, a little after midnight, I walked out the side door of the hospital. It didn’t make sense to me that the night was so alive with the sound of cicadas and frogs when inside, no more than thirty yards away, this boy was lying dead on a stretcher. I wondered what his parents were doing, if they had any idea their son wasn’t home. Maybe they were already on their way to the hospital. I wondered what my mother was doing-probably sleeping-and if she was dreaming about me. And if she did dream about me was it the twelve-year-old me or the current twenty-three year old version? Was I the same person to her? Never changing, just her son, always and forever?

This was all rolling around my mind when Rothco walked out. He was in his forties, shaved his head and rarely smiled. I took the cigarette from him, puffed on it twice and tried not to cough. He lit his own cigarette, then said, “Sorry to make you X-ray that kid back there.”

“It’s part of the job,” I said. “People die everyday.”

He raised his eyebrows and nodded as if to say sure, try and be tough. After exhaling a wall of smoke, he said, “My mother is dying.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Pancreatic cancer. Every morning when I get home I expect to find her dead.”

This was the most he’d ever spoken to me. I wondered if he’d seen me almost lose it in there when I had to lift the kid’s leg and set it on a X-ray cassette and how I had to wipe my face to keep from crying. If this was his attempt to comfort me in some way.

“I moved in with her and went to nights three months ago when she got sick,” he said. “This way I’m with her during the day and she’s sleeping when I’m at work.”

Out across the road, a pair of bats circled a street light, consuming bugs, completely in control of their flight. I didn’t feel in control of anything.

“Sometimes I go and check on her, on my lunch break. Just to make sure she’s breathing,” Rothco said.

“I’m sorry,” I said again, as if it was the only phrase I was capable of using tonight. I’d whispered those same words to the dead boy when the two of us were alone in the trauma room. Cars drove by on the road-their speed and the darkness-making it hard to tell the make or model, sometimes even the color. Around the corner from us, a woman was talking on a cell phone, telling someone that her baby had a fever.

Rothco took a final drag of the cigarette and tossed it on the ground, stomped it out. “I’m going to ride over there now, check on her. You want to come? Twenty minutes round trip.”

More cars pulled in the ER parking lot and I wondered if one of them might be the kid’s parents. I imagined them breaking down, crying, when they saw their little boy. His face was bruised, but not too bad, and I hoped the fact there was little evidence of the trauma he’d suffered would give them some peace. What they wouldn’t be able to see was the swelling in his brain and how both of his femurs and his pelvis were fractured.

“Yeah,” I said. “I’ll go.” I’d told Ray, the other 3rd shift X-ray tech, that I needed to get some air, but I’d deal with him when I got back, say I decided to go ahead and take my lunch.

When Rothco turned the key of his truck, Johnny Cash boomed from the door panels. We drove through one of the neighborhoods that bordered the hospital, heading in the opposite direction of the apartment I’d moved into three months ago, after finishing X-ray school, leaving my mother in our house by herself. I moved out because I had a real job and could afford it and I was an adult; it was time to go. But now, I felt guilty for leaving her. My father had been gone for over a decade and my sister moved to North Carolina two years ago.

“You know,” Rothco said. “If you’re going to stay in this game a long time you’ll see a lot worse than that kid. You’ll see babies with limbs missing, burn marks on their foreheads. You’ll see shit you won’t ever forget. Some nights, I swear, it’s like fracture city in there.”

“Great,” I said.

“You could always go work at McDonalds or the mall.” I knew he was joking, but I didn’t laugh; it wasn’t funny. None of this was. We didn’t speak again until we pulled into his mother’s crushed stone driveway. The house was white and square, much bigger than the one I’d grown up in. There was a row of Palm trees in the front yard, down by the road, and a wooden fence circled the back yard. Rothco climbed out and shut his door, then opened it again. “You coming?”