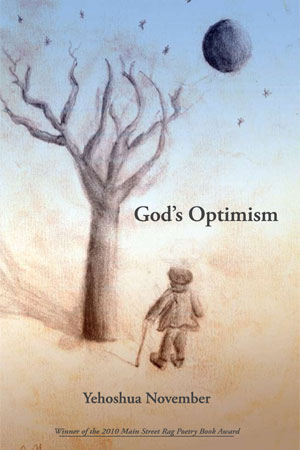

poems by

Yehoshua November

Poetry book, 92 pages, $14 cover price

($12 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-264-4

Released: 2010

WINNER of the 2010 Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award

FINALIST for the 2010 L.A. Times Book Prize.

$14.00

In stock

poems by

Poetry book, 92 pages, $14 cover price

($12 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-264-4

WINNER of the 2010 Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award

FINALIST for the 2010 L.A. Times Book Prize.

Yehoshua November

Yehoshua November

God’s Optimism is Yehoshua November’s debut poetry collection. In addition to winning the MSR Poetry Book Award, it was named a finalist for the Autumn House Poetry Prize and the Tampa Review Prize for Poetry. November teaches writing at Rutgers University and Touro College, and his work has appeared inThe Sun, Prairie Schooner, Margie, The Forward, and other publications. His poetry has been anthologized, nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and selected as the winner of Prairie Schooner’s Bernice Slote Award. He lives with his family in Morristown, NJ.

God’s Optimism is a highly distinctive and original book, a book of serious spiritual devotion. The struggles and emotions of the book are compelling in ways that even a non Jewish audience would be moved by. In other words-this is a work of art. I read God’s Optimism with great pleasure.

–Lynn Emanuel

The invisible world and the mundane one are always rubbing shoulders in Joshua November’s crafted, imagistic poems. I admire and am moved by the spirit of stillness, and honesty of inquiry of these small landscapes and stories. They are tender as candlelight, and full of the sorrowful mirth of their tradition, which treasures the unknowable.

–Tony Hoagland

FOREWORD

I remember the first time I met Yehoshua November, many long years ago in an introductory poetry class. I went around the room asking each student an ice-breaking question that felt, even then, a bit perfunctory: why did they write poetry? When we came to Josh (that’s what we called him then), he said, “I want to restore the sanctity to language.”

The class was startled. I was stunned, and never forgot it, partly because over the years I have watched him wrestle to do just that. Yehoshua went on to finish his undergraduate and advanced degrees, become a teacher, marry and raise a family. But he has never stopped writing poetry and he has never stopped trying to restore an essential sanctity to language. I feel him grappling with the spiritual in every poem–as Jacob said when he wrestled all night, “I will not let Thee go except Thou bless me.” Even when the poem is about apparently mundane subjects–tennis, billboards, Harpo Marx, a tangerine–this tension between the daily and the sacred hums just under its skin.

Reading this glorious book of poems, one of the finest I have read in decades, part of me thinks, well of course God is an optimist if He’s still got someone like Yehoshua November on his side. Sanctified but never sanctimonious, many of the poems in God’s Optimism dive into the subjects of desire, longing, passion. “When I was a student/ love treated me like a road,” November writes in “The One Who Has Left You.” He goes on: “because you will find yourself/ sitting alone in a movie house,/ watching the film you planned to see together./ And the man on the screen/ will have dark eyes and a distant face/ but the woman will have the eyes/ of the one who left you.” –But there is no telling when there will be a reconciliation: “Then one day the radio returns/ in the middle of the same song,/ like a man waking to finish the sentence/ he began before his coma./ And the lovers, too,/ take up each others’ bodies once again,/ but now they are old/ and the love making is slow and awkward, like the first time.”

Many of the best poems here are love poems for his own wife, recalling “when, despite the school of nervous fish/ that swam through my heart,/ my hand found yours/ for the first time.” These are not ordinary love poems, bound up in them are contradictions, gratitude, and a sense of having found the bershert, or fated one: “if you must rouse me,/ please, my wife,/ do not even place your small hand/ on my shoulders,/ but whisper my name,/ remind me that I am such and such a man/ and you are the dark-haired daughter of so and so,/ chosen for me/ before I took up this journey.”

No book of poems can be truly great which does not stretch its attention and compassion toward the larger world. November does this again and again. He goes back in time to the notes his grandmother wrote his grandfather, “Hard boiled eggs on the stove. I believe in you.” With great gentleness he reaches for the gifts of his ancestors, “we push our fingers to the back/ of our sock drawers/ and bring the ancient bow ties to the lamp light.” Or further, to the last century, the Frierdiker Rebbe cast out of Russia, “The soul is never in exile.” He reaches outward as well, to “the nearly naked supermodel/ advertising a watch” on a billboard, whose third marriage is falling apart. He remembers the traveler, “in a foreign province,” and his lonely meditations: “not unlike carrying a cello/ through a winter night,/ the dark wood rotting/ in the snow.” He writes with compassion about the suicide’s father; about “The dark children swimming in the ocean/ off a small town in Chile/…And what about God? If God is infinite, we cannot explain/ the sadness of the world/ without drowning him.”

To read God’s Optimism is to remember what poetry is meant to be: musical, tender, philosophical, generous-hearted. When I read November’s poetry I am ashamed ever to have called myself a poet, for I know I am in the presence of a young master-as honest and witty as Kafka, as visionary as Doestoevski, but with a voice and presence all his own. This book is an astonishing debut. While rooted deeply in its Jewishness, it speaks to people of all faiths, and of no faith. The first person (among many) to whom I will gift this book is a lay Catholic priest, for I know it will speak to him. There is nothing holier-than-thou in November’s sanctity of language. It is filled with contradictions and dualities, as many of the poems’ titles suggest, “Anything Infinite Must be Unknown,” “Upstairs the Eulogy, Downstairs the Rummage Sale.” I will gladly give the book to the local Chassidic rabbi’s wife, or to my wildest, most rebellious student with pink and blue hair.

November’s work has been published in the most prestigious literary magazines, has won awards, been anthologized, and is destined to reach an ever-widening audience. His voice is magically lyrical, “and every voice could be the one/ that dissolves in the forest/ or the song that holds/ the necklace of the lake.” More than that, it shows wisdom far beyond his years, for November is still a young poet, and one could hardly expect such depths from a writer three times his age. I’ll end by quoting one of my favorite poems, “Tennis,” in full:

One evening you will walk past a park

between two fading apartment buildings,

and see men playing tennis in white garments,

and long to slip out of your life,

to be buried in the white robe with no pockets,

and float like a ball

between two rivals, two great friends,

this world and the next.

What you hold in your hands, reader, is not just a book of poems, but a treasure.

Liz Rosenberg,

July 2010

Samples

Upstairs the Eulogy,

Downstairs the Rummage Sale

The beloved Yiddish professor

passed away on the same day

as the synagogue’s rummage sale,

and because they could not bear

the coffin up the many steps

that led to the sanctuary,

they left it in the hallway downstairs,

and because I was not one of his students,

and it didn’t matter if I heard the eulogy,

they told me to stay downstairs,

to watch over the body and recite Psalms.

And I thought,

this is how it is in the life and death of a righteous man:

upstairs, in the sanctuary, they speak of you in glowing terms,

while down below your body rests beside

old kitchen appliances.

And I recited the Psalms as intently

as I could over a man I had only met once,

and because I knew where he was headed,

and you and I were to wed in a few months,

I asked that he bring with him a prayer for a good marriage.

And this is how it is in the life and death of a righteous man:

strangers pray over the sum of your days,

and strangers ask you to haul their heavy requests

where you cannot even take your body.

Cleaning out Zaide’s Apartment

For My Grandparents

His scent still lingered in the black heat

of his darkroom, where he spent decades

developing his meticulous world

of insects and flowers.

Boxes of slides

lay piled on top of one another.

Holding one to the lamplight,

I entered a different universe,

where moths silently cling to the stems

of roses.

In the bedroom

we found tie clips in the shape of airplanes

and then the slender, fragile model planes

he had built from scratch and hand painted

bright blue with yellow emblems on the wings.

And in every drawer,

countless notes she had written to him.

He must have saved them all,

each one wedding the mundane to a private world

only the lovers themselves could know:

Hard boiled eggs on the stove. I believe in you.

Before I Took Up This Journey

Before God opens his fist

to let a soul gently descend into this world,

He whispers a name, an occupation, a future bride:

“So and so the architect will marry so and so the teacher’s daughter.”

If I lie asleep in my bed-

wherein the Sages say a man’s soul goes back,

and he is partly dead-

if you must rouse me,

please, my wife,

do not even place your small hand

on my shoulders,

but whisper my name,

remind me that I am such and such a man

and you are the dark-haired daughter of so and so,

chosen for me

before I took up this journey.

You must be logged in to post a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.