Becky Gould Gibson

Becky Gould Gibson’s poetry has appeared in many journals, including Connecticut River Review, CAIRN, Hiram Poetry Review, Iris, Kalliope, Ekphrasis, Feminist Studies, Brooklyn Review, 10th Muse, Shearsman, The South Carolina Review, Chiron Review, The Comstock Review, and The Texas Review, as well as in several anthologies, the most recent of these, Don’t Leave Hungry: 50 Years of Southern Poetry Review (University of Arkansas Press, 2009) and Adrienne Rich: A Tribute Anthology (Split Oak Press, 2012). Becky has published two prize-winning chapbooks of poetry, Off-Road Meditations (North Carolina Writers’ Network, 1989) and Holding Ground (White Eagle Coffee Store Press, 1996), as well as three full-length volumes: First Life (Emrys Press, 1997); Need-Fire, winner of the 2005 poetry book contest held by Bright Hill Press (published 2007); and Aphrodite’s Daughter, winner of Texas Review Press’s 2006 X.J. Kennedy Prize (published 2007). Need-Fire also received the North Carolina Poetry Society’s 2008 Brockman-Campbell Award. Becky won the 2012 William Matthews Prize from the Asheville Poetry Review for her sonnet sequence “Heading Home” and an 2012 International Publication Prize from Atlanta Review for “The Supernumerary” and “Selling Sorrow.”

Earning a Ph.D. from UNC-Chapel Hill in 1977, Becky has taught literature, writing, and Women’s Studies, mostly at Guilford College where she retired after twenty years in May 2008. Since retirement, she served two terms as Gilbert Chappell Distinguished Poet for the Central District (2009-2011); currently she is a member of the Forsyth County Historic Resources Commission. What she does for fun, when she’s not at her desk, is hang out with her goofy little granddaughter.

Becky Gould Gibson’s Heading Home is quite simply a virtuoso performance. She pulls out all the stops, uses all the instruments, shows in extraordinary ways what she can do with language. She honors Stevens, and Swift and Yeats by writing not only about them but in their styles. Her remarkable “royal crown” sonnet sequence that both ends the book and supplies its title is a stunning account of the evolution of a baby’s life from conception to birth. And if that were not enough her poems about the natural world and our relation to it evoke over and over a sense of life’s preciousness and its fragility. I don’t think there is anything that Gibson can’t do. This is a book to read over and over. —Anthony S. Abbott, author of If Words Could Save Us

Heading Home is erudite—you learn when you read Becky Gould Gibson—without a bit of stuffiness. References range from Yeats and Stevens to Plato and Socrates to Jane Fonda and The Today Show. The ancient and the modern, the sacred and the profane commingle in the collection—sometimes in the same poem, as her funny, perceptive “Saint Paul at the Coin Laundry.” As at home writing about theology and philosophy as barbecue and blue damsons, Gibson is adept at form, draping lines so naturally over the underlying structure you don’t realize the form on first read. In the title poem that crowns the collection, Gibson revisits the Word-made-flesh talk of earlier poems, stands the trope on its head (literally, as the baby in the womb drops head down for birth), making the flesh of the fetus into the words of this stunning sonnet sequence that leaves you reconsidering your own place in this world, our home. —Celisa Steele, author of How Language Is Lost

The poems in Heading Home, Rebecca Gould Gibson’s passionate new book are as dimensional, as surprising, as holographs. She holds up to the light things we have seen all our lives and they shimmer and shape-shift into a wholly, often blinding, wildly imagined new world replete with cameos by Pericles, Churchill, Saint Paul, Saint Augustine, Swift, Wallace Stevens and Yeats. Her speakers traipse with impunity through the invisible portals of the past. Beneath her pen everything yields; everything metamorphoses. As she says in “Summer Solstice in Pastels,” “Can we ever see anything as it is with the field always changing?” Gibson is a zealous poet—a contemplative, in truth—with an ear cocked to the earth, her seer’s eye fixed on the sky, the daily offices of life mythologized in stunning revelation. —Joseph Bathanti, Poet Laureate of North Carolina

MORNING, SIMPLE SPRINGS FARM

We step out of a painting—oil, Hudson River

School—blue cows milling in the distance, through

a pasture to the pond, lit up like a dance floor,

mist lifting like tulle. I want to show you

the red-winged blackbird, flashy reed-dweller,

unfolding wings to lacquered fire. Tease with

a brief red semaphore. Magician in his private coat,

inside pockets stocked with red handkerchiefs.

But this morning he refuses to strut his stuff,

saving up, we suppose, for the big act at noon,

sun his sidekick. You’re reminded of a childhood

bird book, Scarlet Tanager, your favorite bird,

more for the words than the color. Good name

for a stripper, you tell me. Scarlet Tanager,

her name in lights, swings stage-ward from rafters

on heavy rope, perch wide enough for her seat

as well as her plumage. Walks into the audience,

winks at all the men, some of the women,

plucks out each scarlet feather, one table at a time.

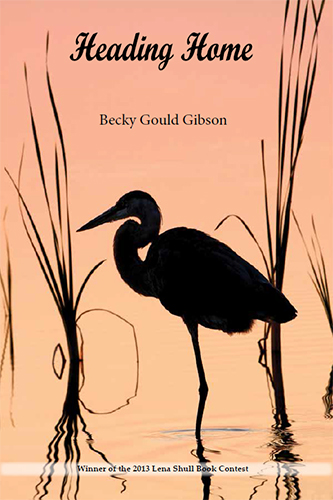

THE GREAT BLUE

He calls you great blue with affection, both of you keen-eyed

fishers who stand patient for hours, if need be,

though he tells me he’s not tied a fly in years.

On a cold, cloudless day at the dead end of January,

we watch from a floating boardwalk

as you draw your long narrow legs through the shallows.

Head down, you step gingerly.

Before the recent trouble, he made boats and fishing

tackle boxes of walnut or mahogany with antique brass fittings.

You use those huge wings to mount a log

maybe six inches higher than where you were standing,

slip upon landing. Brief boarding!

Why even bother for so little distance?

Did you need a lift? A better view of the depths?

Did it help relieve boredom?

He chuckles with fraternal indulgence.

He’s had a rough time himself lately, the pickings slender.

Now he’s hit bottom.

Bird, why am I telling you this?

What can you know of dejection?

Dear heron, dear brother. Birds of a feather.

You’re gray-blue, he’s brownish,

both of you balding,

both of you, for the moment, beating the odds for survival,

both of you with a foothold in chilly swamp waters.

When you turn your head to one side, it almost disappears into light.

JULY MEADOW

The townspeople see fit to leave it, mow around it.

A meadow gives me courage—

candid grasses happy almost anywhere.

No holding out for something greater,

the smallest wind sets them going.

A goldfinch flicks in among them,

without a shrug or a flutter,

goes straight for a seedpod,

sits atop the feathery fronds.

His mate comes down wide of him

with her dull brown countenance.

He flies up to the pine, she follows.

Perhaps when napping, she dreams in his colors,

his smart black and yellow.

She loves a man bonny and brilliant.

She loves a man in uniform.

Now he’s hidden. No. I see him.

Landed, it seems, on a culm,

his head bobbing

with the pleasure

of seeds, the weeds’ glory.

In a meadow nothing is given, everything’s earned

little by little:

slightest breeze, slightest motion,

but the payoff is eloquence—

a glance in the green.

That’s him in the yellow,

sun’s mimic,

sun’s bedfellow,

summer riding the grasses.

Slender landing.

How far he swings down without falling!

How I envy his trust in the reed,

lusting for that which sustains him, eating the god.