a novella by

Matt Starr

ISBN: 978-1-59948-666-6, 92 pages, $12.95

Release Date: May 15, 2018

SYNOPSIS

A hapless, conflicted, and road-worn college dropout, Doobie Malone has only ever known two things: his hometown of Beechum, North Carolina, and The Easy, a rundown watering hole as old as the town itself. When he returns after a decade to buy the latter, he believes he might be able to shake the shadows of his past. But while The Easy — like Beechum — seems mundane enough on the surface, its dark, nebulous, and magical qualities suggest otherwise.

Throughout his years at the backbar, Doobie is impelled to weather the elements — both natural and unnatural — of The Easy and Beechum as a whole. He is forced to navigate a history as flawed, violent, quirky, and perverse as his patronage. He is pushed to confront his ghosts — past, present, and future — in a drama that unfolds toward a disastrous, neo-biblical conclusion.

Hell, or High Water is a Southern Gothic novel about the blurred lines of morality and the inherent horror of human nature. It is a tale about the demons of our past coming back to reap what they’ve sown.”

Bookended by two floods, Hell or High Water tells the story of Doobie Malone, from his hard-times childhood to not much better adulthood, as he tries to make good. But no matter how hard he, or anyone else, works or struggles or prays, the looming threat of natural devastation, or mankind’s simple cruelty, always waits to wash everything away. Starr’s novella is a rollicking tale of hardscrabble life in the south. –CL Bledsoe, author of Man of Clay

Matthew Starr’s novella Hell, or High Water is an evocative debut that follows the tormented life of Doobie Malone who lives in Beechum, North Carolina and owns The Easy, a bar with a long history and a dubious reputation. Eccentric characters, violence, local tragedy, and destructive floods haunt the pages. Never disappointing, Hell, or High Water leaves the reader hoping that Starr will revisit this small Southern town sometime in the future. –Robert Bateman, Over the Garden State and Other Stories

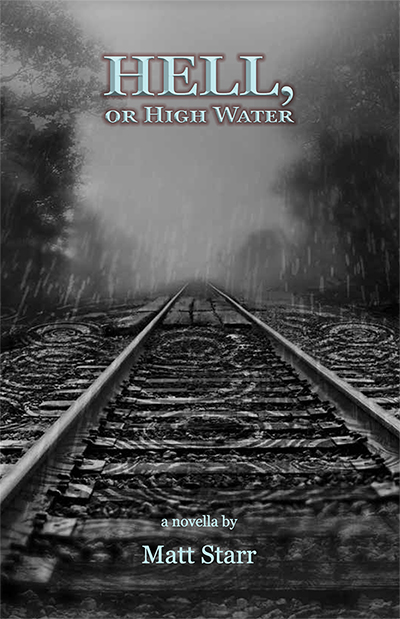

“My daddy told me, lookin back

The best friend you’ll have is a railroad track.”

–Tom Waits

I.

Doobie Malone bought The Easy for a thousand bucks in 1968, twenty-one years before the flood. It sat in an old lot tucked under the sweetgums on Styx Road in Beechum, North Carolina, and behind it, ran a decaying railroad that meandered four hundred miles into the north across two state lines.

“She ain’t what she used to be,” Old Man Corkwell said through a jaw full of chewing tobacco swollen under rawhide skin. He deposited his sun-mottled hands into the pockets of his overalls. “But who the hell is?”

Doobie propped his arm on the black bootlegger sign wedged in the roadside earth and admired the dwindling gold typeface within; he ran his fingers over the frayed edges and looked to the building ahead. This version of The Easy wasn’t the first or even the second; it was the third. A bloodthirsty wolfdog had plagued the area back in 1871 before a local tobacco farmer killed it with his bare hands. Afterward, a Cherokee elder blessed those same hands, and the farmer used them to erect the original building, which was a local staple in the Reconstruction South. Rumor had it that even President Johnson had made it in there at one time or another. The specifics were lost in translation.

Nearly a century newer, this version of The Easy, which Doobie stared at now, sat on the same plot of land. It was a little sand-colored joint with vinyl-sided walls and wind-worn saffron awnings hanging above a porch that left it more reminiscent of a house than a bar. It wasn’t much to everyone, but it was something to Doobie—even if he didn’t exactly know what that something was. He rocked back and forth on the balls of his feet as he stared at it, mystified under a low sky slivered with see-through clouds and pin-cushioned with stars. In his mind Doobie saw the pale, ropy child with rib bones bulging beneath ragged overall straps, his naked feet dyed brown with loose earth. He watched him throw glances left and right, and scuttle around the building and into the darkness, colorless and cold as the bottom of a well.

“Reckon you want to see the inside of this thing or are you content with dickin around out here til the owls start to hootin?” Corkwell asked, his drawl as thick and sticky as the resin oozing from the surrounding trees.

Doobie snapped out of it. “Yessir,” he said with courteous, albeit weak words, mindful of his deddy’s decree that he always respect his elders. But Doobie knew what the inside of The Easy looked like. He’d been gone for over a decade, but he’d grown up less than a mile away, and in Beechum, places were like people: they didn’t really change too much at their core. Doobie knew that better than anyone. His accent was subtle, and he didn’t dress like he was from the area. His spectacles were horn-rimmed, his Oxford shirt was untucked, and his shiny, ankle-cut boots didn’t bear a scratch to speak of. He wore his hair long and pushed to the side on top, and blended short on the sides like the city slickers at the West Coast ad agencies. He looked like he’d been trying too hard to get out all his life. And he had been. He was a hair shy of thirty, but he felt worn down—like he’d lived someone else’s years on top of the ones he’d lived for himself. But when it came down to it, he was still the same barefoot kid dragging his Louisville slugger through the tallgrass up the road, ducking into the nightshade of The Easy’s outer dark.

His Paw Paw Virgil had dropped dead and left him a Mason jar stuffed with a thousand dollars in mostly ones. Moonshine money. The note attached to it went something like this:

Sorry your deddy was a bastard. Regards, Virgil Malone.

After that, Doobie had reckoned it was time to stop running and come on home.

“Come on now,” Corkwell said, plucking at his chin whiskers. “Rita’ll have my ass if I ain’t home in time for supper.”

The two men crossed the dirt parking lot, Doobie limping at Corkwell’s side and sweeping billows of topsoil in his wake.

“You all right there, son?” Corkwell asked.

Doobie acknowledged his left leg. It started to hurt. “Yeah,” he said. “Just an old hitch in my giddy.”

They ascended The Easy’s uneven front steps. Doobie followed as the old man shooed off swirling hornets, humming and weaving in and out of the eaves overhead. The planks of the porch were rickety, and when stepped on, they griped like a chain gang at dawn. A long, backless bench lined the wall to the left of the door, and buckets that served as makeshift spittoons bookended either side of it. To the right of the door, rusty hooks extended from the far corner where a swing once hung and bars dressed the lone front window.

“Unsightly, ain’t it?” Corkwell said, nodding toward The Easy’s only window.

Doobie smirked. “A little bit.”

“Well, you know how them sonsofbitches act when they get to drinkin and carryin on,” Corkwell said, flinging the screen door open. He looked back at Doobie. “And if you don’t, you’ll understand directly.” He twisted a skeleton key into the lock of the front door and pushed through.

Doobie filed in behind the old man and stood in the heavy darkness just beyond the threshold of the entrance. He saw nothing at first, save the shadows of objects cast by the dying daylight outside. The room was muggy and dense, and the stale odor of cigarette smoke in the air hugged him like an old relative he’d only seen at family reunions. Corkwell flipped the switch just inside the door, and the flame-shaped bulbs of the ceiling fan in the middle of the room flickered on as its wicker-patterned blades began to churn noisily. A sheet of soot, ghostlike and powder-fine, stirred into the air and across the room as if awakened. The lounge area was cluttered and dim, but otherwise large. An old Seeburg jukebox with smudged, domelike glass and faded gold plating leaned against the wall in the corner. Cobwebby tarps and bed sheets lay draped over stools and tables strewn across the dingy wooden floor. In the back, a walnut timber bar ran along the exterior wall, its grainy reddish brown countertops lacquered with the residue of spilled drinks. A single stainless steel well with dusty bottles sat perched against it; Doobie studied the cracked mirror above it. And the strangest déjà vu sent shivers through his bones.

“She’s seen better days. But I don’t reckon I have to sell you on her; you already signed the papers,” Corkwell said in front of a deadpan laugh, his Indian corn teeth gleaming. “She ain’t too bad off, though, mindin I ain’t had her open for a month. I’m just ready to get out from under her.”

“She’s perfect,” Doobie said as nostalgia continued to drip from his eyes. Two words he never thought he’d say about The Easy rolled off his lips like a beer bottle from a table, breaking over the floor and spreading through the cracks.

“Well.”

A short period of silence followed, musty and awkward.

“The regulars pretty much keep to themselves,” Corkwell finally said. He gushed tobacco juice into a clay mug as he led Doobie into a narrow corridor beyond a rust-speckled exit sign at the back of the room. “There’s the commode,” he said, tipping his head toward the restroom door on his left. “Cain’t say I’m gonna miss it, no sir.” He unlatched the sliding lock of the next door just beyond it and pulled it open. The viscid warmth of the blue night crept into the passageway as Doobie trailed the old man onto The Easy’s back deck, a rotten-slatted platform littered with cigarette butts and moldy, x-marked jugs. He looked around, eyes dancing to the song of the moon-drunk crickets below. Weather-scarred trees hung over a lawn thick with crabgrass—and a stone’s throw beyond it—train tracks carved through the ground and stretched as far as the eye could see on either side. The child from earlier was skipping alongside it.

“Well that’s the dime tour,” Corkwell said, scratching his chin and mulling over anything he might have forgotten. “If you got any questions, I reckon I can call it the best I can.”

Doobie didn’t say anything.

“Oh, before I forget, make sure the lids are on them trashcans good at night less’n you want the coyotes nosin through.” He grunted. “But hell, it ain’t my place no more so who am I to tell you your business?”

Doobie nodded, his eyes still fixated on the railroad.

Corkwell looked at it too. “And that—” he paused. “Well, we all know what that is.” He withdrew the skeleton key from the bib of his overalls and placed it in Doobie’s open palm. “Good luck to you, son.”

Doobie closed his hand and studied the train tracks—eerie in the way they gripped the earth and bent onward into the distance.

If you like what you’ve read so far and want to read more, order a copy of from Hell, or High Water by Matt Starr

Matt Starr was born and raised in the mill city of Kannapolis, North Carolina, which serves as the primary inspiration for his work. While attending NC State University, he studied under a prestigious faculty of award-winning and best-selling writers. His breakthrough short story, “Phoenix,” was published by The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature in December of 2016. He lives in Raleigh with his girlfriend and their corgi, and works as a content writer for a local marketing firm.

Matt Starr was born and raised in the mill city of Kannapolis, North Carolina, which serves as the primary inspiration for his work. While attending NC State University, he studied under a prestigious faculty of award-winning and best-selling writers. His breakthrough short story, “Phoenix,” was published by The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature in December of 2016. He lives in Raleigh with his girlfriend and their corgi, and works as a content writer for a local marketing firm.