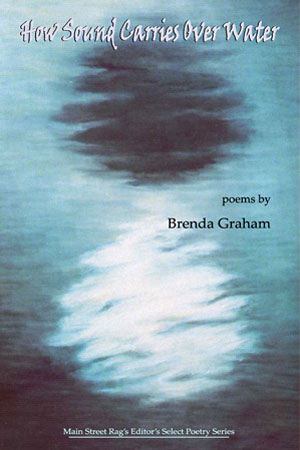

poems by

Brenda Graham

Poetry book, 66 pages, $14 cover price

($10 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-147-0

Released: 2008

* * * This book was selected for publication after finishing as a finalist in the 2008 Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award * * *

Brenda Graham grew up in Columbia, South Carolina, where she absorbed the Southern traditions of story telling, colorful characters and finding meaning in life’s difficulties. She attended the University of South Carolina and has lived in Texas, Alabama and Georgia. Brenda began to write as a child and has won accolades for her poetry, including first place in the Charlotte Writers’ Club poetry competition in 1998 for her poem “Moth” and several awards from the North Carolina Poetry Society. She has been published in Southern Poetry Review, Wellspring, Main Street Rag, Mount Olive Review and Cincinnati Poetry Review, as well as other journals and anthologies. Brenda’s passion for spirituality has led her to teach writing workshops at spiritual retreats for women, teaching poetry-writing to children, leading children’s sermons at her church and volunteering in her community. Brenda has two grown daughters and one granddaughter, who has already begun her own love affair with writing poetry. Brenda lives in Denver, North Carolina.

Brenda Graham grew up in Columbia, South Carolina, where she absorbed the Southern traditions of story telling, colorful characters and finding meaning in life’s difficulties. She attended the University of South Carolina and has lived in Texas, Alabama and Georgia. Brenda began to write as a child and has won accolades for her poetry, including first place in the Charlotte Writers’ Club poetry competition in 1998 for her poem “Moth” and several awards from the North Carolina Poetry Society. She has been published in Southern Poetry Review, Wellspring, Main Street Rag, Mount Olive Review and Cincinnati Poetry Review, as well as other journals and anthologies. Brenda’s passion for spirituality has led her to teach writing workshops at spiritual retreats for women, teaching poetry-writing to children, leading children’s sermons at her church and volunteering in her community. Brenda has two grown daughters and one granddaughter, who has already begun her own love affair with writing poetry. Brenda lives in Denver, North Carolina.

What does one make of a legacy left by alcoholic parents? If you’re Brenda Graham, you make poems of startling imagery and originality. You find a way to navigate through life’s disappointments to forgiveness of others and yourself. These poems reveal what lies beneath the surface. In this skillful first book Graham examines language itself, the meaning behind words. And when she writes the light in this house is changing, you believe her.

—Gail Peck

In Brenda Graham’s extraordinary collection of poetry, How Sound Carries Over Water, we enter the life of a young girl—a life filled with alcoholism, betrayal and yearning—and follow her into a marriage that eventually breaks apart. The pain she experiences matures her into a woman who embraces and grows beyond the past that shaped her. Brenda’s poems are like dragonflies that skim over the surface of the water, swooping with delight and diving unexpectedly into the depths of darkness. Her poetic voice is exhilarating and unique, a voice that lifts and drops us into a new place where grace abounds. The narrator in Cardinal wonders, if I had what it took/ to shatter my rippling image,/ make it to the other side, whole and singing. She does, and the reader cannot help but feel the exuberance of her song.

—Ann Campanella

ANY OTHER MAN’S DAUGHTER WOULD BE CRYING

I’m keeping up with Daddy,

hurrying through Earlwood Park

to reach the Red Dot Store before it closes.

I hang back, slightly,

eyeing the girl on the bright green swing.

Like a marshmallow she is, white

jacket billowing, cotton candy sky

returning her to the man

who must be her father. He kisses

his blonde confection, sends her cloudward, screaming.

Daddy has taught me not to be weak.

He makes me pick my own

switches from the hedge, stings my legs,

You’d better not whine. So I don’t mind,

this sun-toasted September day,

being left outside, holding peppermint sticks,

my nose pressed to the window.

I watch him finger amber bottles, grab

his favorite, Southern Comfort.

On the way home, Daddy walks ahead,

brown bag cradled

in the crook of his arm.

The swing is empty now,

a soft wind moving it

to sing its unoiled song.

EVERY SINGLE SUNDAY OUR FAMILY GOES

TO ARSENAL HILL PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH

and we praise the Lord

and the choir sings, Sweet

and Low, Sweet and Low

and a stained-glass Jesus holds little children on his knee

and Daddy wears a suit made of blue and white seersucker

and walks down the aisle

and passes a brass dinner plate up

and down the pews and people give and give

and Daddy sits down beside me at the end of the third oak pew from the front

and I snuggle like a doll between him and Mama

and my head is in his lap

and his hand is on my blonde hair

and his fingers move and move behind my ear

and an angel floats in from the August heat

and settles in the fans that ladies use to cool their faces

and the preacher pounds the pulpit

and still, I fall asleep.

SHAME

I want to be deaf to my little sister’s screams,

They’re fighting again! She stands

like an orphan, beneath the midnight moon,

beating her fists against the storm door

of my best friend’s house, where I’m free

to lie on Patsy’s bed beneath a cloud

of eyelet comforter, eating butter creams,

listening to Elvis and Ricky Nelson.

I want to be blind to the rocky yards

I pick my way through on the way

to our house, my sister’s hand a bud in mine.

Blind to the shattered glass

that haloes my mother’s head, the way

she lies, crumpled, at the bottom of the porch steps,

my father at the top, hurling goddamns

and empty whiskey bottles,

the neighbors in robes and slippers,

pulled from sleep to see our family on display,

Those Joneses, again. I want to be numb

to the seed that has planted itself

and swells inside me, like tonight’s opaque moon.

Brenda Graham grew up in Columbia, South Carolina, where she absorbed the Southern traditions of story telling, colorful characters and finding meaning in life’s difficulties. She attended the University of South Carolina and has lived in Texas, Alabama and Georgia. Brenda began to write as a child and has won accolades for her poetry, including first place in the Charlotte Writers’ Club poetry competition in 1998 for her poem “Moth” and several awards from the North Carolina Poetry Society. She has been published in Southern Poetry Review, Wellspring, Main Street Rag, Mount Olive Review and Cincinnati Poetry Review, as well as other journals and anthologies. Brenda’s passion for spirituality has led her to teach writing workshops at spiritual retreats for women, teaching poetry-writing to children, leading children’s sermons at her church and volunteering in her community. Brenda has two grown daughters and one granddaughter, who has already begun her own love affair with writing poetry. Brenda lives in Denver, North Carolina.

Brenda Graham grew up in Columbia, South Carolina, where she absorbed the Southern traditions of story telling, colorful characters and finding meaning in life’s difficulties. She attended the University of South Carolina and has lived in Texas, Alabama and Georgia. Brenda began to write as a child and has won accolades for her poetry, including first place in the Charlotte Writers’ Club poetry competition in 1998 for her poem “Moth” and several awards from the North Carolina Poetry Society. She has been published in Southern Poetry Review, Wellspring, Main Street Rag, Mount Olive Review and Cincinnati Poetry Review, as well as other journals and anthologies. Brenda’s passion for spirituality has led her to teach writing workshops at spiritual retreats for women, teaching poetry-writing to children, leading children’s sermons at her church and volunteering in her community. Brenda has two grown daughters and one granddaughter, who has already begun her own love affair with writing poetry. Brenda lives in Denver, North Carolina.