I’ve Been Warned Not to Write About This

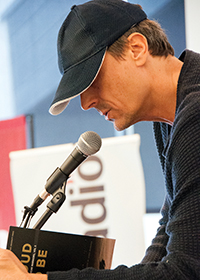

poems by

Ron Riekki

This project has been canceled.

Refunds will be issued to those who pre-ordered.

$14.00

Out of stock

poems by

This project has been canceled.

Refunds will be issued to those who pre-ordered.

Ron Riekki wrote My Ancestors are Reindeer Herders and I Am Melting in Extinction (Loyola University Maryland’s Apprentice House Press), U.P.: a novel (Ghost Road Press), and Posttraumatic: A Memoir (Small Press Distribution). He edited Undocumented: Great Lakes Poets Laureate on Social Justice (Michigan State University Press), And Here: 100 Years of Upper Peninsula Writing, 1917-2017 (MSU Press), Here: Women Writing on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (MSU Press, Independent Publisher Book Award), The Way North: Collected Upper Peninsula New Works (Wayne State University Press, Michigan Notable Book), The Many Lives of The Evil Dead: Essays on the Cult Film Franchise (McFarland).

Ron Riekki wrote My Ancestors are Reindeer Herders and I Am Melting in Extinction (Loyola University Maryland’s Apprentice House Press), U.P.: a novel (Ghost Road Press), and Posttraumatic: A Memoir (Small Press Distribution). He edited Undocumented: Great Lakes Poets Laureate on Social Justice (Michigan State University Press), And Here: 100 Years of Upper Peninsula Writing, 1917-2017 (MSU Press), Here: Women Writing on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (MSU Press, Independent Publisher Book Award), The Way North: Collected Upper Peninsula New Works (Wayne State University Press, Michigan Notable Book), The Many Lives of The Evil Dead: Essays on the Cult Film Franchise (McFarland).

Fire burns through these poems like truth—from California, to hazmet suits, to the impeached president’s distain for science—to people like Riekki himself who work as first responders, teachers in prison, who know PTSD. This is a kind of holy book of witness—a fire ritual. The opposite of diatribe, it is an ovation to language that speaks truth. “This is not theater” Riekki tells us, “but rather our lives, my life, your life.” ~Joy Gaines-Friedler, author of Capture Theory

To “feel good enough to grace God with belief,” is to appeal to Blake’s Muse: To see bloodshed where the comfy see bullion; to know that God commissions Bible verses, not bullets, and commiserates with poets, not plutocrats. Ron Riekki is that United Statesian-Saami bard, who knows that Prez Delirium Tremens is “a David Duke of Earl,” and that a person, “killed in slow motion” equals “an adult being born.” Here’s biopsy—not autopsy. ~George Elliott Clarke, Poet Laureate of Canada, 2016-18

Read this book—not for comfort, but for truth. In poems that counter political propaganda with a powerful accumulation of guns, ghosts, and “hands. . .covered in oil,” Riekki lifts the veil of consumer culture to show us our lives of “violence as normal,” reminds us “this is not theatre.” Himself birthed in trauma, the author puts on poetry like a hazmat suit, here kneels to offer CPR to an America, pistol-shot and burning. ~Kimberly Blaeser, author of Copper Yearning, Wisconsin Poet Laureate 2015-16

The kid walks up to the fence.

He is bleeding from his leg

and arm and face and chest.

Imagine what looks like hoof-

prints of blood splattered all

over, almost comical; there’s no

need for that much blood.

I’m just off break. I’m union.

We get two breaks per shift.

I sleep in the back of my car.

It’s my time. I can do what-

ever I want for those fifteen

minutes. My hair sticks up.

He says he needs help. I go

to dial 911 and he says, Ain’t

you 911? No, I’m not a cop,

I say, I’m an EMT. Doesn’t

that stand for medical some-

thing? I tell him I’m an EMT

for the factory. I can’t climb

over the fence. He says he’ll

climb over the fence. I tell him

no, that I have to call the cops

if he does that. I feel like an

idiot. He tries to climb but

he’s too cut up, too hurt. I

asked what happened. I see

a kid behind him, lying there.

What happened? I ask. Just

playin’ around. I’ve seen

patients with this much blood

before. We have workers

whose arms get caught in

the machinery. They get

degloved and eviscerated,

avulsions. I get them too.

A drunk employee punched

me in the cheek before,

the eye really, the cosmos

I see permanently if I close it.

I tell the kid that he’s gotta stay

on his side of the fence. I have

to stay on mine. He tells me

I’ll burn in hell. The factory

behind me pours smoke out

like it’s fighting to own the sky.

I ask where he’s bleeding

the most. He says he doesn’t

know. I say it again, angry.

He tells me his leg. I tell him

to put pressure on it, to not

take the pressure off. I tell him

to put it above his heart. He says

he can’t, it’s his leg. I tell him

to figure it out. How do you get

your leg above your heart? He lies

down. He holds his leg. The kid

in the background starts holding

his own arm. They’re controlling

the blood. I get down on the ground

and I look up at the sky too.

When I taught in prison, I told the prisoners

that if they murder someone on the page,

they can win an award, but if you murder

someone in real life, you’ll end up back

here in prison. One of the guys raised

his hand and said, What if you kill the person

who gives you the award? The class liked that.

I’d arrived by foot, but the parking lot greeted me anyway with a gala

of sun, as if the past, the onomapoetic plot!, was barbecued, ready to be

eaten, shared, trashed; I wish this hilly bliss could blizzard the vets

drowning in the intrusive flashback nets, could fix their hashed exits

with the new days of denouements, to be rescued by relief,

decluttered, as if ungunned, the agony gone, fileted;

there are times you feel good enough to grace God with belief.

When newspapers died,

their son

took over

the business

and he liked boobs,

so he’d write

obituaries

about boobs

and show boobs playing

golf

and he made the weather report

a boob weather report.

The boobs

appreciated the fame.

In the old days,

boobs couldn’t be

involved in politics,

but now boobs

run for President

every year.

When the newspaper industry

died,

it was from all of those years

of smoking,

or,

excuse me,

sucking,

all of those years

of sucking

all of the air

out of the room

to make room

for the boobs.

Here’s a news

flash.

Here’s a news

peep show.

Here’s a noose.