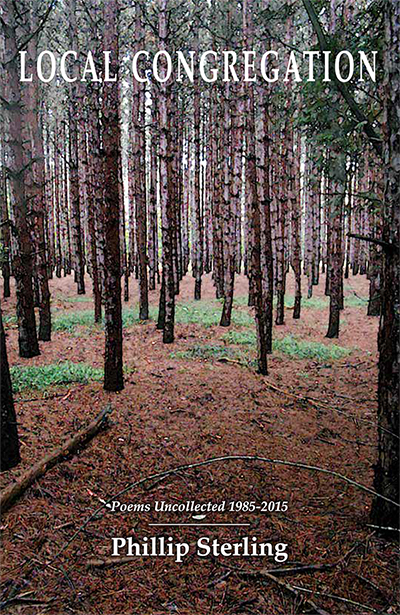

Local Congregation

poems by

Phillip Sterling

ISBN: 978-1-59948-977-3, 88 pages, $15 (+ shipping)

Projected Release Date: October 10, 2023

The Advance Sale Discount price on this title has expired. For those who prefer to pay by check, the price is now $19/book (which includes shipping) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, 4416 Shea Lane, Mint Hill, NC 28227.

PLEASE NOTE: Ordering in advance of the release date entitles the buyer to a discount. It does not mean the book will ship before the date posted above and the price only applies to copies ordered through the Main Street Rag Online Bookstore.

Phillip Sterling’s previous books include the poetry collections And Then Snow and Mutual Shores, two collections of fiction, In Which Brief Stories Are Told and Amateur Husbandry, and five chapbook-length series of poems, most notably Short on Days, which was released from Main Street Rag in 2020. An associate poetry editor for Third Wednesday Magazine, he lists among his awards a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, two Fulbright Awards (Belgium and Poland) and selection as artist-in-residence for both Isle Royale National Park and Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. He lives in Lowell, Michigan, where he and his wife, Jane Wheeler, tend a small woodlot and several gardens and care for an extravagance of animals and insects of questionable domesticity.

Phillip Sterling’s previous books include the poetry collections And Then Snow and Mutual Shores, two collections of fiction, In Which Brief Stories Are Told and Amateur Husbandry, and five chapbook-length series of poems, most notably Short on Days, which was released from Main Street Rag in 2020. An associate poetry editor for Third Wednesday Magazine, he lists among his awards a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, two Fulbright Awards (Belgium and Poland) and selection as artist-in-residence for both Isle Royale National Park and Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. He lives in Lowell, Michigan, where he and his wife, Jane Wheeler, tend a small woodlot and several gardens and care for an extravagance of animals and insects of questionable domesticity.

Phillip Sterling’s poems have always blended a mastery of craft and precision with a deep, reflective awareness and insight, and Local Congregation is certainly no exception. Here, we find a poet at the height of his powers. With humor, humility, and grace earned through years of paying attention, he shines light on the small moments until they glow with insight and discovery. Sterling listens closely to the undercurrents, and we should all listen to him. ~Jim Daniels

Local Congregation is aptly named, both in what’s found at hand (“local”) and in “congregation” as this is a collection of poems (as congregants) from the writer’s literary church, if you will. Wonderfully built and compressed, snappy with wit and wisdom of the natural and spiritual worlds, these Frostian poems glimmer brightly. Careful readers will be singed and touched by Sterling’s good words, as in “Beginnings”: “the stories of one’s life strung out / from off-side the heart, fabricated // if need be, the worst forgotten. . . .” ~Patricia Clark, author of Self-Portrait with a Million Dollars and The Canopy, Professor Emerita of Writing, Grand Valley State University

The Holy Ghost

When the first maple husks bark like

latex house paint water’s gotten under

we curse the road crews, the salt trucks,

in our doubting blame the county.

After all it begins near the road. Soon

grass southeast of every winged-seed

browns to sourdough; our ears fill; we

hear through the night insects burrowing.

Soon we are called to hapless constellations,

white grubs scattered like snow peas

—haphazardly—among moist roots of rye.

So let’s say we plan to lace the dawn

with pesticide; and say, instead,

our witness lifts to dibs of sod upturned

above the bark beetles beneath those trees.

Say we sense the paw-scent of skunk; and

say it is a skunk, yes, some blessed creature

come to feed its white belief bright larva.

One Speaks of Longing

On the first morning of snow the old move

like the huge lumbering Chinook that start

the children screaming and waving and bring us

full panic to the edge of Mitchell Creek,

thinking: It must come to this,

certain that we’d need to wrestle coat sleeves—

and small body—from the bony, clutching roots

of a washed-out tree. But no, it’s only fish,

though of size and number we’d never seen there

before, and moving unnaturally slow:

green-finned Pacific winds purling the rock-

strewn shallows, hurling the culvert’s yawn

beneath the railroad tracks—desperate to spawn,

yet hardly able to heave their darkened bodies

upstream, slow as old fishermen, whose stories

are all the fishing they’ve done in years . . .

Or like the children’s grandfather, who tumbles

in his excitement, his church shoes hopeless

on the slick embankment, his astonishment

staggering. Again we think the worst:

Accidental, Before his time, This time for sure,

the dazzling, unfortunate final dowsing . . .

But wait! He rises on his own (as if knowing

we’d not reach him in time), regains his balance,

and will live to become a story—if not the history—

of wet clothes. So who’s to say who’s meant

to be saved? And who’s to say who’s meant

to laugh, as my father did, in the face of

death’s sport? Who’s to say we’re not all

meant to be lumbering, knowing that the snow

will pull us under eventually, that we will

abandon the rush and struggle, the stories

of our longing to return, of our turning onto

our sides and going back to sleep? (Who’s

to say we can’t go back, not even in longing . . . ?)

Look. Our skin pales like milt, blanches and

peels; our hair grays in comparison. We have

spawned, or had hoped to. And suited in

our clumsy waders we welcome the first snow.

Now Boarding

Let’s say you get on a plane.

You hadn’t planned to,

you really have no place to go,

but you were at the terminal

anyway, and on a whim

you take the next flight.

It doesn’t matter where.

Call it something in the weather,

a drizzle so low you’d found

it difficult to stand up,

and when the plane lands safely,

you catch the next flight

out of there—Chicago O’Hare,

Minneapolis, Pittsburgh—

the first available seat,

and launch into clouds

that refuse to stay in one place

long enough to be anyone’s

property, and when you land

in a rush of belonging

to the earth, you take the next

flight from there—Los Angeles,

Dallas, Phoenix—buckle in

and begin to look forward

to small difficult packages

of lightly salted pretzels,

an extravagant beer.

If you’re lucky, the flight

is interminable, full meals

will be served. If you’re lucky,

as you reach your cruising

altitude and speed

the sun will lock its glint

to the wing, and time will

become a sky spreading below

as though a pharmacist

in a momentary lack of faith

unseals countless quantities

of orange pill bottles and

strews their cotton stoppers

across a gray-green countertop.

There are good reasons to fly:

One is when you have to,

you’re expected, and travel

is the door you forgot to lock,

the pets you’ve boarded in

unsanitary kennels, desire

softening like overripe melon.

Another is when there’s no

reason not to, when no place on

earth can hold you, no one’s

found waiting at the gate

—bound to inquire about your

flight—when no one

who’s come to see you off

decides to leave with you

on the very next plane.

Phillip Sterling’s previous books include the poetry collections And Then Snow and Mutual Shores, two collections of fiction, In Which Brief Stories Are Told and Amateur Husbandry, and five chapbook-length series of poems, most notably Short on Days, which was released from Main Street Rag in 2020. An associate poetry editor for Third Wednesday Magazine, he lists among his awards a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, two Fulbright Awards (Belgium and Poland) and selection as artist-in-residence for both Isle Royale National Park and Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. He lives in Lowell, Michigan, where he and his wife, Jane Wheeler, tend a small woodlot and several gardens and care for an extravagance of animals and insects of questionable domesticity.

Phillip Sterling’s previous books include the poetry collections And Then Snow and Mutual Shores, two collections of fiction, In Which Brief Stories Are Told and Amateur Husbandry, and five chapbook-length series of poems, most notably Short on Days, which was released from Main Street Rag in 2020. An associate poetry editor for Third Wednesday Magazine, he lists among his awards a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, two Fulbright Awards (Belgium and Poland) and selection as artist-in-residence for both Isle Royale National Park and Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. He lives in Lowell, Michigan, where he and his wife, Jane Wheeler, tend a small woodlot and several gardens and care for an extravagance of animals and insects of questionable domesticity.