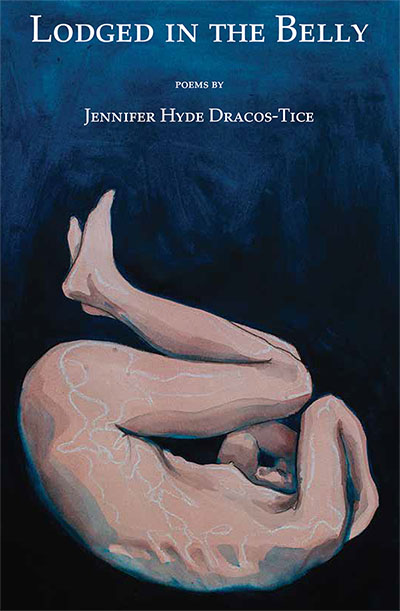

Lodged in the Belly

poems by

Jennifer Hyde Dracos-Tice

80 pages, ISBN: 978-1-964277-25-7, $15 (+ shipping)

Release Date: November 12, 2024

The Advance Sale Discount price on this title has expired. For those who prefer to pay by check, the price is $19/book (which includes shipping & sales tax) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, 12180 Skyview Drive, Edinboro, PA 16412.

PLEASE NOTE: Ordering in advance of the release date entitles the buyer to a discount. It does not mean the book will ship before the date posted above and the price only applies to copies ordered through the Main Street Rag Online Bookstore.

Screenshot

Jennifer Hyde Dracos-Tice has poems published in Witness, Psaltery & Lyre, Crab Orchard Review, Still: The Journal (2016 Judge’s Choice Award), Literary Mama and elsewhere. A long-time high school English teacher with literature degrees from Brown and Indiana-Bloomington, she lives with her wife in Florida.

In her remarkable debut collection, Jennifer Dracos-Tice creates a haunting tapestry of poems that gives witness to deep familial sorrow and deeper resilience. Embracing light and shadow, she fashions a universe from both personal affirmation of family trees and public erasure of redacted court documents. She transforms it all into a brilliant song: of truth, reckoning, and a search for her mother’s lost family. A song that leaves us breathless—in awe, wonder, and joy. ~Linda Nemec Foster, author of Bone Country and The Blue Divide

Beginning with the blood of birth, Lodged in the Belly painstakingly maps a complex family history, tracing the way families break and keep breaking, and the mystery of how, from this brokenness, comes something akin to holy. In poems that tell a gripping human story, full of unexpected twists and turns, Jennifer Hyde Dracos-Tice reminds us of how many ways there are to make and remake a family, and of the abiding truth of love. ~Cecilia Woloch

After Birth, 2001

I want to see the afterbirth

splay in its glimmer bed,

branches veining under

its veil of red, roping

and threading to the organ’s thick margins.

Amnion manta ray, filter and feeder.

The metal tray pulls the scale

whose needle jumps, corrects.

Focus on your baby, the OB instructs,

but I strain to glimpse

that ruddy braid

—oh, purple wizened hand,

heart a-swirl—

last bit of us bathed in my blood.

The doctor shifts, lights glare.

He whisks bowl and bowel away,

discards the flattened contents,

hands me the dry-wrapped bundle.

Tonight, my son cries in his plastic crib

next to my hospital bed. Something stirs

in silt under a planet’s worth of water,

lodges its barb deep in my belly

and tears.

On Hearing a Rumor Years Later That My Mother’s Biological Father Might Have Kept a Receipt for Her Birth

Someone mentions a folded paper

from Emory Hospital

with a date and price paid,

his signature over amount

tendered. Was it stuffed

into piles of other slips, bills

of exchange pressed like a straw bale’s

layers, sweet rot at the center?

Child of the Great Depression, he

probably resembled so many other men

who recorded every tip, fare, hotel charge—

penciled figures marching across envelopes,

scraps of paper. He might have been

devastatingly handsome in pictures,

a young JD Salinger, shiny black loafers,

long thin legs. He might have been

cruel, thought payment rendered

was the end of her. He might have

cupped her newborn head.

Interrogating March 24, 1946

Of course I wasn’t there,

that first day of spring—

really a month after

spring arrives in Georgia—

the day you were born,

as far as we know. The facts

are hazy, like your own mother’s

mind, emerging from ether,

belly slack.

Family legend recounts

your birth at Emory Hospital,

though Emory had no maternity ward,

and your original birth certificate

remains sealed.

You believe your birth mother

hid at Florence Crittenton

Home for Unwed Mothers.

This was after the war,

when new adoption policies cut

postpartum hospital stays, a way

to preempt any chance

of bonding, to ensure babies

were adopted out. Psychologists

had a new term for white

middle class women who gave birth

out of wedlock: neurotic—

those who longed for pregnancy,

not sex. Which meant your mother

could escape the label deviant,

could start again, clean. But where

were Crittenton babies born?

At the house on North Peachtree?

Were you? Your adoptive parents

told you the obstetrician—

a cousin to your adoptive father—

gave you to them at birth, that they

adopted you legally months later.

What home? What hospital?

Dr. Matthews, bespectacled,

might’ve driven to the brick colonial

that March evening, performed

a delivery in your birth mother’s

room at the Crittenton Home—

a few dresses in the closet,

suitcase in the corner.

He might’ve brought a nurse—

pinned cap, tight lip—

to carry the bundle of you

in the backseat, back

to his office at Emory.

Family whispers, much more recent, challenge

everything. Your adoptive father might have worked

with your birth father at Lockheed during the war.

Perhaps they arranged a private adoption.

Witnesses, whoever they were,

all dead now.

Helen Writes to Marianne: An Imagined Letter

I’ll be dead before you see this,

the seizures keep getting longer, leave me

so tired. You are still mine, despite

your long nose, hazel eyes,

no features like my own.

You were so alert (is that my beautiful baby?)

when we got you—God knows

where Ed got you. I knew better

than to ask. Even when his business failed,

and then our marriage, there you were—

book in hand, pounding along the hall

on your brother’s heels. My tremors

shook me so hard I couldn’t call

for you, I couldn’t stop his terrorizing.

I know what he did to you behind

that door. But my legs were lead,

and my hands couldn’t push the wheels.

And you kept following him back to his room,

warren of wires, radio carcasses. I had to

stop him. I had to send you away. I know

you were angry, remember your last quick hug,

as you bent to me in my chair. Please. You know

your Meemaw always forgave your father

and your brother. I couldn’t leave you

with those men.