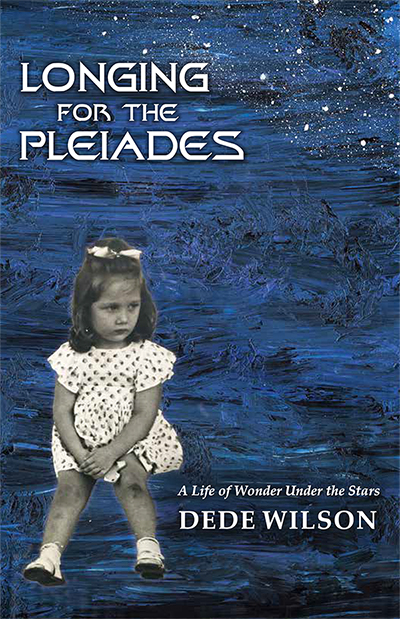

Dede Wilson’s Longing for the Pleiades: A Life of Wonder Under the Stars is a rigorously readable memoir of the delights and complexities of a charmed youth and adulthood, and the inevitable pain of loss – a daughter to a drunken driver and a husband to the mysteries of Alzheimer’s. Wilson’s genius is her poet’s eye for the fetching detail: Her maternal grandmother’s domed ceiling of stars (the Pleiades) in her entrance hall in Natchez, Miss. The inmate Brown whose freedom Wilson’s senator grandfather bought from Mississippi’s Parchman Penitentiary to be his chauffeur. Wilson’s glimpse of JFK in Dallas moments before he was shot, “stopping mid-wave to brush the hair from his eyes.” Dede Wilson relishes her life. How lucky that she’s sharing that life with us. ~Dannye Romine Powell, Winner of the Roanoke-Chowan Award for her poetry collection, In the Sunroom with Raymond Carver

Take a trip with Dede Wilson, from her colorful childhood in south Louisiana to that barbaric day in Dallas, from the farthest points on the globe—Nairobi, Caracas, the Valley of Elah—to the deepest imaginable loss. In Longing for the Pleiades, Wilson invites you to share her adventurous life as well as some closely-held secrets of the heart. Come along; you’ll be glad you did. ~Stephen Knauth

Even while imagining the days approaching her own birth, when her expectant mother waits “in wonder and pain” knowing that what awaits her new child is a world “seamed with subterfuge and regret,” Dede Wilson acknowledges and celebrates both wonder and pain: two necessary sides of the same coin, each informing the other. In Longing for the Pleiades, Wilson’s arresting hybrid collection of prose and poetry—and, yes, even recipes!—this gifted writer reveals, page after page, how imagination works alongside research and memory to create the richest form of knowing, one “caught in certain breezes that watched at the time and caress me still.” ~Rebecca McClanahan, author of In the Key of New York City: A Memoir in Essays and The Riddle Song and Other Rememberings.

A SMALL TOWN CALLED MANSURA

Daddy’s family embodied the rich flavor of south Louisiana—and this was a foreign land to my Mississippi mother. Here, the women haunted the kitchen, laughing at themselves, dipping a tasting spoon into the etouffee, dripping hot water one tablespoon at a time over the grounds in the white porcelain coffee pot. Growing up, my mother Dot had not been allowed in the kitchen. Her mother always had a cook and the cook was in charge. Food appeared when you pressed the buzzer under the dining room table.

Being in the country was not what Mama resisted. She’d been born in rural Mississippi, had lived there until she was ten, when her family moved to Natchez. What Mama resisted in south Louisiana was the culture. People making comments in French, leaving her baffled. Children allowed to roam through the small town without a hovering parent. Food so savory you could swoon just to smell it cooking. There were creamy green beans and cornbread muffins and sweet potatoes, which Mama loved, but to my mother, many of the foods seemed bizarre: dirty rice (long-grain rice laced with minced liver and kidney), boudin (blood sausage), cracklings (roasted pork rinds). Mama’s worst memory was the night she and Daddy attended a south Louisiana crawfish feast: everything crawfish, even the appetizers. She could not look at the food. Who would want such things?

Mama did learn to cook. She could make a scrumptious pot roast (brown each side in an iron skillet before adding vegetables and cooking), crispy cornbread served with silky greens, beautiful pound cakes. Her egg custards were incredible. She’d caramelize the sugar over a low flame, pour this into custard cups, then put a pat of butter on top before adding the stirred custard (eggs, milk, sugar, vanilla) and baking. She never loved cooking, though, the way Daddy did. He could crisp a chicken, butter an oyster stew, and pat out the best short biscuits you’ve ever drenched in syrup and closed your lips over.

There’s a story our family loves to tell. Soon after Mama and Daddy married, Daddy decided he’d like a little steak for dinner. He went out and bought two steaks, took them into their kitchen and told Dot (I’m sure with a kiss or two) he’d love for her to cook them. He’d started a small garden, so he went out to work in his garden, anticipating a fine supper. When he came in, hungry, he sniffed around for tantalizing aromas. Nothing. He found his young wife lying on their bed, weeping. He was baffled.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“I’ve never touched raw meat!” Dot wailed.

Pete cooked the steaks.

And Mama soon learned to cook most anything.

Mama tried hard with Daddy’s family, but their ways were too different from hers. There she was, laced in her rigid ancestral corset, and there they were, waiting to loosen her laces. Oh, how they’d tease! Every time Daddy drove us to Mansura for Sunday dinner, we’d leave with one savory chicken and one last word from my grandfather.

“Now Pete will have something good to eat for a change!” he’d say.

Mama would ride home in tears. Oh, yes, she took it personally. There was no way to be a part of that family if you couldn’t take the teasing, if you couldn’t see the affection in it.

The teasing and the tossing. I was airborne before I could sit up. One uncle threw me so close to the whirling ceiling fan Mama fainted. Or almost did. In spite of the joshing and jostling, I adored being in the country. We’d gather warm eggs from under the hens, climb the chinaberry tree and blow the green berries at each other through hollowed out sugar canes, ride the horses through the back pasture. Once I was riding bareback and my horse bolted toward a closed gate, Mama chasing behind. I clung to the mane, breathless, knowing the horse would jump, but it stopped short at the gate.

If I say I’m from Louisiana, some will exclaim, “So you’re Cajun!” But, no, my paternal ancestors on both sides were what they called French Creoles. French Creoles are descended from the French who immigrated directly to this country from Europe. Cajuns are the French who had settled in Canada, in Acadia, and migrated south when they were expulsed by the British. We are not connected by blood to the Acadian French and share no common surnames. John James Audubon was a French Creole.

On the paternal side of Daddy’s family, we’d find the first immigrant to this country to have been Dominique Baldony. Though the name Baldony (variously spelled Baldonide, Baldoni or Baldonie) is said to be Italian, the name is of pre-7th Century French origins. Records state that Dominique Baldony was one of the early French immigrants who settled in Louisiana in Pointe Coupee parish, eventually fleeing some 30 miles northwest to higher ground in Avoyelles parish, to a town called Mansura, after the great flood in Pointe Coupee in 1780.

Here is how the Baldony family lost their surname. In Pointe Coupee, Dominique Baldony operated a floating store on the Mississippi. Among those who traded with him were the Choctaw Indians, and the Indians began to call him “l’homme de coco,” or “the man with the coconuts.” So our ancestor became Monsieur Coco and his descendants carry the name to this day.

Except, to complicate things, my Coco grandfather—Edward Aurelien Coco—was called Mr. Ed. It followed that my grandmother was always referred to as Mrs. Ed. In her case that appellation was contracted to Miz Ed, which sounded like Mizedd.

If you walked through my grandparents’ front door, you entered a central hall that extended the depth of the house. This hall was so long the grandchildren were allowed to run and slide in their sock feet to the end of it. In winter, it was closed off and left unheated; we dreaded that icy passage. Haunting the hall was a large hand-colored photograph of my daddy’s brother Ashton. Before I was born, Ashton had died suddenly, at 28, of endocarditis. No one was allowed to say his name. Though an adult when he died, Ashton will remain, to his unmet nieces and nephews, that mysterious little boy in the photograph, buttoned into a white coat and pants, who silently stared down at us as we sock-slid that hall.

Outside, on the north side of the house, was a rose garden. In the back were tall peaked pines we’d shimmy till the high slender limbs folded under our weight. Behind this yard were the chicken coops. We’d reach beneath the hens to fetch their warm eggs or chase the roosters unmercifully.

Not a stick of grass emerged from the front lawn. It was a dirt yard, and Miz Ed often appeared with a broom to sweep leaves and debris away. My cousin Suzanne and I would play in a moss-covered ditch that ran along the side of the house. The moss became rugs, the sticks our tables and chairs, the acorns people. But we weren’t playing house under the low-hanging trees. In this French-speaking town we would have said to one another, “Let’s play madam.”

The long sidewalk that passed in front of her house led to town. Every time we visited, Daddy would take me by the hand or carry me down that street to St. Paul’s Catholic Church. We’d enter the rectory and go straight to Father Nothofer’s office, a small room that held the aromas of leather and books and cigar smoke. We called him Paterre, and when he’d pick me up as a small child, I’d be enclosed in a cloud of him. The old priest loved me as fiercely as he loved my daddy, whom he’d known since birth, and being held by him felt like being blessed. Sometimes Daddy and I would eat our noon meal at the long table in the dark wood-paneled refectory with the priests and nuns, and I would sit there, too fascinated to eat.

Back at my grandparents’ house, it didn’t hurt our pleasures that children old enough to sit at the big table were served glasses of wine. Not diluted with water. Straight wine. It was pretty safe to do as none of us liked it very much, but we’d take tiny sips and pretend.

After an enormous noon meal that might include three meats and several kinds of potatoes, the children would dash to the screened porch and either climb into the Morris chair to play Chinese checkers or fight over the chaise longue. This chaise longue was a huge black leather affair, one end rising up like a psychiatrist’s couch. We would lie there under the ceiling fan and sometimes the mosquito net, listening to bees thrum against the screens, and fall into a full-belly sleep. If it rained, we’d lie there, enchanted with the sound on the porch’s tin roof. Several times we mimicked communion with food that was meant for a cousin’s goldfish. We’d break the thin white wafers and place a piece on each other’s tongues, feeling guilty.

Sometimes we’d go outside and pick some honeysuckle, pull the stamens and savor that speck of sweet.

Lurking somewhere would be my daddy’s older brother Lysso, the one who reveled in tickling us and throwing us into the air. He had a movie camera and I starred in two of his films. In both, I’m a small child, probably two or three. Responses to these old movies illustrate something I can’t quite name, perhaps the core of our human condition. In one, I’m on the ground, crying. My older cousins are pulling my arms, my legs, my hair. You might say they’re picking on me. In the other I’m the delightful child, bow in my hair, skipping and bouncing up and down the long concrete sidewalk that extended like a popsicle stick from my grandparents’ front steps.

When the first movie is shown, where I am the tortured child, my Louisiana cousins watching the film always rock with laughter. It makes me laugh as well. When the other is shown, where I’m the carefree child, my sister says it makes her sad.

AUNT BIRD’S GREEN APPLE BREAD PUDDING

1 loaf French bread

1 quart whole milk

Soak bread in milk, then smush.

When soft add following mixture:

4 eggs, beaten well

2 cups sugar

2T vanilla

1/2 cup white raisins

1 green apple, diced, skin on

Melt 3/4 stick butter in 8 X 13 pan.

Add mixture to pan.

Bake at 325 for 45 minutes.

WHEN READY TO SERVE, cover with WHISKEY SAUCE

and put under broiler briefly.

(Serve hot or warm. Can be frozen and reheated.)

WHISKEY SAUCE

1 stick butter

1 cup sugar

1 egg

1/4 cup bourbon

Melt 1 stick butter in double boiler, cream in 1 cup sugar. Cook while stirring

until sugar dissolves and mixture is creamy. Remove from heat and whip in

1 beaten egg, fast! Add 1/4 cup bourbon. Stir in well.

(I halve this recipe as it is way too rich.)

Spread sauce over cooked bread pudding, then heat under broiler.

SERVE

WHEN YOUR FEET

CAN’T TOUCH THE BOTTOM

Though truth will briefly light

upon the surface, little I see

is clear or predictable. My eyes

are level with the glare and water

gnats annoy my brows. A stone

that cannot skip, I float

too close to drowning. I am

no more than watersnake–

quick eye, quick line, divining.

Colder and colder my lonely pond

till I am clasped in ice.

I wait for the thaw,

the break of wet lilies

wild for the light.

Dede Wilson’s first book of poetry, Glass, was published by Scots Plaid Press as runner-up for the 1998 Persephone Press Award. Her second, Sea of Small Fears, won the 2001 Main Street Rag Chapbook Competition. Eliza: The New Orleans Years, a finalist for both the Perugia Press Award and the Pearl Poetry Prize, was published by Main Street Rag. Some 150 national literary journals have published her poetry and short stories and two of her poems were nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Dede Wilson’s first book of poetry, Glass, was published by Scots Plaid Press as runner-up for the 1998 Persephone Press Award. Her second, Sea of Small Fears, won the 2001 Main Street Rag Chapbook Competition. Eliza: The New Orleans Years, a finalist for both the Perugia Press Award and the Pearl Poetry Prize, was published by Main Street Rag. Some 150 national literary journals have published her poetry and short stories and two of her poems were nominated for a Pushcart Prize.