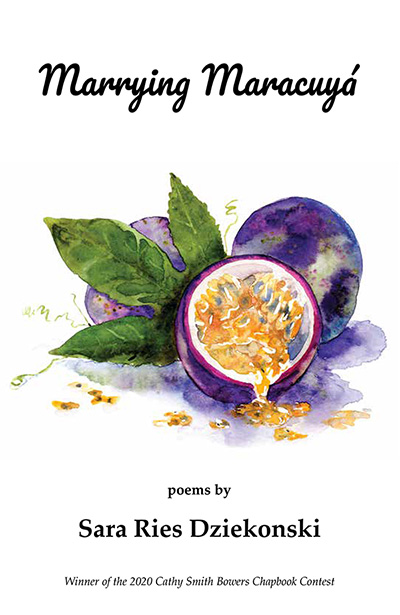

Marrying Maracuyá

poems by

Sara Ries Dziekonski

WINNER of the 2020 Cathy Smith Bowers Chapbook Contest

ISBN: 978-1-59948-864-6, 50 pages, $13 (+ shipping)

Release Date: April 19, 2021

For those who prefer to pay by check, the price is $17/book (which includes shipping) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, PO BOX 690100, Charlotte, NC 28227-7001.

Sara Ries Dziekonski, a Buffalo native, teaches creative writing and lives in St. Petersburg, Florida with her husband and year-old son. Her first book, Come In, We’re Open, which she wrote about growing up in her parents’ diner, won the Stevens Poetry Manuscript Competition and was published in June 2010 by the NFSPS Press. Her chapbook, Snow Angels on the Living Room Floor, was released in 2018 by Finishing Line Press. She holds an MFA in Poetry from Chatham University. Her poems have appeared in Slipstream, Punt Volat, Cordella Magazine, Blue Collar Review, and Cathexis Northwest Press, among others.

Sara Ries Dziekonski, a Buffalo native, teaches creative writing and lives in St. Petersburg, Florida with her husband and year-old son. Her first book, Come In, We’re Open, which she wrote about growing up in her parents’ diner, won the Stevens Poetry Manuscript Competition and was published in June 2010 by the NFSPS Press. Her chapbook, Snow Angels on the Living Room Floor, was released in 2018 by Finishing Line Press. She holds an MFA in Poetry from Chatham University. Her poems have appeared in Slipstream, Punt Volat, Cordella Magazine, Blue Collar Review, and Cathexis Northwest Press, among others.

I once heard poet James Seay describe an experience in his life as one of those moments you wish you could marry forever. From Buffalo to Bogotá and back, this poet has, indeed, found a way—through the art and craft of poetry—to marry these landscapes and their people forever. She has given us a true love story with the feel of a five-act play—exposition, rising action, turning point, falling action, and denouement. I love the energy, the tug and pull between toughness and tenderness, the various poetic strategies so masterfully wielded. Bravo! What a gift she has given us! ~Cathy Smith Bowers, former Poet Laureate of North Carolina and Contest Judge

Before We Leave the Deep Freeze of Buffalo

Bob’s shooting darts,

his usual cup of ice

in a pitcher of Blue

to keep it strong and cold.

It’s the coldest winter

we can remember.

Big Mike, the resident debater, agrees.

Joe enters, says, stomping

his boots back to brown,

Why do we live here?

It’s my last Monday shift

and slow, again,

before Tall One and I pack up

the apartment’s guts,

shove them into storage

to roam around Colombia,

not knowing what the hell we’ll do

once three months are up.

Our guidebook says: Colombia,

the only risk is wanting to stay.

Bob studies the dart tip,

seeds of dreams crushed

between forehead scrunches.

Why would you want to go there?

Cocaine. Cartels. Kidnappings…

But Bob never danced in a sweaty spiral

to Musica Folklorica from the Andes,

never scaled a mountain just to touch

the stone Jesus I’d say goodnight to,

prayerless from a bedroom window,

was never handed a latte topped with a foam heart

in a courtyard of begonias in February,

and told Buen provecho, voice

an ancient love song.

The First Time I Tasted Maracuyá

A short wrinkled woman with scarred hands

sliced the purple skin and offered me

its slimy guts.

I was unsure of the taste,

my mouth a pail of water.

Maracuyá gripped me like a new lover

wearing the wrong scent of strong cologne

but by the second bite

I felt sixteen again, sneaking out of the tent at midnight

to meet that long-haired guitarist on the beach,

swearing to myself we’re only going to kiss.

You know maracuyá,

that concert that leaves your ears ringing for days

or that time you couldn’t feel your knees and suddenly

you were the world’s best dancer.

Maracuyá, that sour french kiss

and you’re wiping your mouth

with stacks of napkins.

Now I crave the rock star of fruits.

More maracuyá, por favor, siempre.

Give me helado maracuyá, maracuyá con leche,

until I’m marrying maracuyá,

looking life in the eyes, promising

with my deepest bones I do.

My Island Mama

Marlyn, my landlady,

won’t let you sit on her patio

until you praise her flowers.

Ask her how she’s doing. I bet she’ll say

Excellent, thanks to the Lord, drinking

the salty humid air.

She’s ten feet from my bed

in a bright red blouse

singing to Jesus like she does every morning

as she sweeps bougainvillea petals off the patio.

The family of cats I adopted

thumps across the tin roof.

I jump out of a bed that’s hard

by North American standards, toss on clothing,

tripping over pant legs, swing open

the top door. Good morning, Marlyn!

I say to my landlady and offer a café tinto,

black and strong like me, she says,

and her roaring laughter shakes

an unripe guanabana from the tree.

She asks why my cousin’s traveling partner, Joyce,

when they visited last week, was always like this,

and demonstrates by bouncing her head around

with an upturned nose. This is paradise, she exclaims,

el paraíso, does a shoulder-shake dance, kissing the air above.

Her eyes get small; she leans in.

Ever notice the people dem like that

get the fly or cockroach in their food

at the restaurant?

Well, Joyce was sipping a Mai Tai

on a daybed at the beach,

when a baby coconut fell and wacked her knee.

I heard her screams from the sea.

I tell Marlyn: I think she was expecting a Hilton in Los Almendros.

We live in The Almonds, a fifteen-minute walk in the scorching sun

to the beaches, two minutes if you hop on the back of a motorcycle

with no helmet, tell the man with the handles on your life

para las playas, por favor, en el centro

and when you arrive safely, hand him dos mil pesos.

I don’t know what she was so unhappy about,

Marlyn says, and laughs. This is the best place on the island,

and she’s right. Even with the ant colony nesting in the cupboard,

the obligatory cockroach, the shower the pressure of tears,

hers is the best place.

And if you can’t tell by the crystal punch bowl,

bone china tea set, or kaleidoscope of monarch butterflies

just outside the door

you’ll know the second she says Welcome!

I carry welcome in my name, she’ll say.

I’m Marlyn Welcome Cruz Downs,

and everyone who stays here

is happy.

Sara Ries Dziekonski, a Buffalo native, teaches creative writing and lives in St. Petersburg, Florida with her husband and year-old son. Her first book, Come In, We’re Open, which she wrote about growing up in her parents’ diner, won the Stevens Poetry Manuscript Competition and was published in June 2010 by the NFSPS Press. Her chapbook, Snow Angels on the Living Room Floor, was released in 2018 by Finishing Line Press. She holds an MFA in Poetry from Chatham University. Her poems have appeared in Slipstream, Punt Volat, Cordella Magazine, Blue Collar Review, and Cathexis Northwest Press, among others.

Sara Ries Dziekonski, a Buffalo native, teaches creative writing and lives in St. Petersburg, Florida with her husband and year-old son. Her first book, Come In, We’re Open, which she wrote about growing up in her parents’ diner, won the Stevens Poetry Manuscript Competition and was published in June 2010 by the NFSPS Press. Her chapbook, Snow Angels on the Living Room Floor, was released in 2018 by Finishing Line Press. She holds an MFA in Poetry from Chatham University. Her poems have appeared in Slipstream, Punt Volat, Cordella Magazine, Blue Collar Review, and Cathexis Northwest Press, among others.