MORTALITY

with Pronoun Shifts

poems by

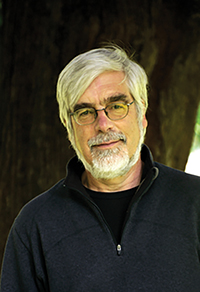

Don Colburn

WINNER of the 2018 Cathy Smith Bowers Chapbook Contest

ISBN: 978-1-59948-732-8, 40 pages, $12 (+ shipping)

Release Date: March 19, 2019

Don Colburn has published five poetry collections, including four chapbooks. A longtime reporter for The Washington Post and The Oregonian, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in feature writing. He has an MFA in poetry from Warren Wilson College. His first chapbook, Another Way to Begin, won the Finishing Line Press Poetry Prize, and his full-length book, As If Gravity Were a Theory, won the Cider Press Review Book Award. Other writing honors include the Discovery/The Nation Award, residencies at The MacDowell Colony and Yaddo, and three Pushcart nominations. He lives in Portland, OR.

Don Colburn has published five poetry collections, including four chapbooks. A longtime reporter for The Washington Post and The Oregonian, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in feature writing. He has an MFA in poetry from Warren Wilson College. His first chapbook, Another Way to Begin, won the Finishing Line Press Poetry Prize, and his full-length book, As If Gravity Were a Theory, won the Cider Press Review Book Award. Other writing honors include the Discovery/The Nation Award, residencies at The MacDowell Colony and Yaddo, and three Pushcart nominations. He lives in Portland, OR.

I loved this book from the get-go. The title itself is a brilliant juxtaposition of opposites: the archetypal, biblical, emotion-laden word mortality paired with such a sterile, academic phrase as pronoun shifts. Throughout the book, this stark tension of opposites never flags. Who wants to read an entire book of poems about death? I’ll take one any day—if it is written by this author. ~Cathy Smith Bowers

Don Colburn is adept at enacting the old exclamation of wonder: Imagine that! as he enters what he reads: the “breaking news” of other lives, imagining what it’s like to be caught in their mortal dramas, even as, with irony and candor, he explores his own encounter with time. Whether in praise or outrage, his poetry doesn’t need to raise its voice, but closely observes, cares for and endows with meaning what it sees. ~Eleanor Wilner

Don Colburn takes a vivid glimpse—at an ancient tree, an artifact, a comment by a stranger—and feeds it his attention, like water to a seed, so this glimpse may grow into a poem to gift us insight. In this book, spirit captions to the visible world take us inside enigmas that have arrested him and kindled these poems. Read their prismatic discoveries that make the ordinary strange, and the mysterious precious. ~Kim Stafford, Oregon Poet Laureate, author of Wild Honey, Tough Salt

Bristlecone Pines

“A great reluctance to die is common among bristlecone pines…”

sign in Great Basin National Park, Nevada

Isn’t it enough

that this one, say, has been around

longer than Jesus or Buddha

and that one’s older than Pliny the Elder

or Roquefort cheese and most if not all

dirt? Can I look at survival

in a weather-beaten tree

and call its twisted beauty

beautiful? The mortal sign maker

insists on more, insists

the ones that faced the worst adversity,

the most relentless wind and drought,

wound up living longest,

outlasting death even, like bones.

That makes a good story,

maybe a fable, and it’s true

their bony branches bristle and snag

the dying light this afternoon.

But I’ve watched for a while now

and the great reluctance isn’t theirs.

Thoreau on his Deathbed

…his last intelligible words ‘moose’ and ‘Indian’…

Library of America

Never one to waste time on the future,

he asked them to carry his attic bed

down to the parlor so he wouldn’t miss news.

He wasn’t looking to save visitors the trouble

of stairs. They knew he was an ornery cuss

with a gift for words and his own way.

When he set the woods on fire,

it was by accident, though he never repented

and neighbors lost good firewood.

I love Henry, said a lifelong friend,

but do not like him. Opposition

was his natural mood, his home

no matter where he walked.

Autumn leaves teach us how to die,

he’d written, but now it was early May.

And what did he mean, really?

That we flare, then fall? That the end

should be a soundless letting go?

And would he stand by that,

lying in the parlor receiving guests,

among them his jailer and Aunt Louisa

and the abolitionist preacher

down from New Hampshire wondering,

with Henry “near the brink of that dark river,”

what he made of the opposite shore?

“One world at a time,” said Henry, still opposed.

Even at 44 he must have seen it coming —

consumption, bronchitis, coughing spells

in the woods as he counted tree rings.

When his doctor advised a warmer clime

Henry ruled out Europe as too costly

and the Caribbean, too muggy,

then left for Minnesota and stayed one month.

Lungs wheezing, he came home to Concord,

to the yellow house on Main Street

and its parlor, his last observatory,

where from his bed he conjured up

an Indian, a moose — news

before the final breaking news.

Why I Read Obituaries

I listen for a distant bell

even when the name is one

I couldn’t have come up with.

Today it was Bruce Langhorne, 78,

his right hand missing two fingers

and much of a thumb, blown off

by homemade fireworks when he was 12,

which didn’t keep him from taking up guitar

and learning so well he played with Dylan

and Baez, Lightfoot and Rush.

From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial

he performed with Odetta before 250,000

the day Martin Luther King Jr. said, “I have a dream.”

There were folk-rock gigs in Hollywood

and a mid-career swerve to Hawaii, where he grew

macadamia nuts. Diabetes inspired him

to cook up organic low-sodium salsa

he sold as Brother Bru-Bru’s Hot Sauce.

Death is the one news hook

late or soon we all achieve

but an obit needs a better reason

to tell its story. Mr. Langhorne’s goes back

to ’64, when he walked into the recording studio

carrying an enormous Turkish drum with bells,

and Dylan, in that jingle jangle morning,

he came following, to sing a song for us.