poems by

Jesse Millner

Poetry chapbook, 38 pages, $7 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-048-0

Released: 2006

Selected for publication after finishing as a finalist in the 2006 MSR Chapbook Contest.

$7.00

poems by

Poetry chapbook, 38 pages, $7 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-048-0

Selected for publication after finishing as a finalist in the 2006 MSR Chapbook Contest.

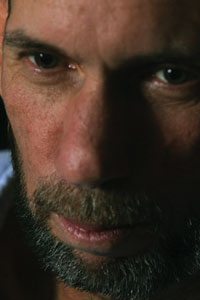

Jesse Millner is an English Instructor at Florida Gulf Coast University. His poetry and nonfiction have appeared widely in literary magazines such as Willow Springs, Gulf Stream, and Third Coast. He is a past recipient of an AWP Intro Award for Poetry and his first chapbook, The Drowned Boys, was published by March Street Press in January of 2005. Jesse lives in Estero, Florida with his wife, Lyn, and dog, Sam

Jesse Millner is an English Instructor at Florida Gulf Coast University. His poetry and nonfiction have appeared widely in literary magazines such as Willow Springs, Gulf Stream, and Third Coast. He is a past recipient of an AWP Intro Award for Poetry and his first chapbook, The Drowned Boys, was published by March Street Press in January of 2005. Jesse lives in Estero, Florida with his wife, Lyn, and dog, Sam

All-Stars of the Bible

My head still buzzes with old sermons

the preacher delivered about the Bible All-Stars:

Noah collecting the animals

in twos, David kicking Goliath’s ass,

the Savior upsetting the temple tables.

But the real hall of fame moment

came when the big guy rose from the dead, fleeing

the dark cave for Paradise. The whole time

our pastor spoke, I thought about girls in my seventh grade class

and the after-school parties where I inhaled

the fragrance of their hair-sprayed heads

during the first slow dance; and I realized

then, religion is the gasp after the quickening, the heavy

breathing in earthly closets, the way the moon glows

on rare California ice, the way cactus blooms at night,

the way the mountains tear black swaths of meaning

from lower elevations, constellations swirling

and dying as stars become dippers and bears,

the way the Eucalyptus green the leaves of morning,

my mother holding my navy father’s infrequent letters,

childhood opening

to a thousand doors,

one of them my Sunday school class at the First Baptist Church in La Mesa

where Mrs. Thomas, large in her cotton dress, asked

me week after week if I’d accepted Jesus as my personal savior;

and when I’d answer “no,” she kept me after class,

depriving me of those blessed minutes before church began

when we’d run around in the playground

out back where the teeter-totter heaved

small bodies into space,

and the cries of children drowned out the fear of hell.

I listened to my fat jailer in the way I often listened to rain in those days,

as if I were in another room, away from the water,

her words disappearing like mist.

She’d march me back into church

where I’d sit next to my mother

in the suffocating dullness of the preacher’s

words interspersed with dutiful hymns

until finally we reached the climax

when all the saved brothers and sisters marched

up to the mourners bench,

their mouths stretched to orgasm

as I listened to the boredom whirring in my head,

and unlike Blake’s terrible angels,

the notes sang neither Hell or Paradise;

I heard the nothingness

of an empty room filled with believers

singing “Oh lamb of God, I call.”

After services, Mrs. Thomas lingered

at the door to give me one last look that said: Without Jesus, you’re lost.

Learn to love God.

I loved the Beach Boys and the Beatles, but most of all Lesley Gore

whom I often conjured naked and singing in my bedroom

during California nights when I left my body

as I kissed her generous lips and touched

her breasts which grew larger in imagination,

a great gift back then, that journey away

from the Baptists and pinto bean dinners,

away from the absence of my father

who was cruising the Med,

away from sermons about the hellfire.

These days I miss the hymn-singing, the way the moon

waned over the Laguna mountains, the way I found

moments of peace beneath the wind flung Eucalyptus

on wild mornings I flew to school down Lemon Avenue,

anticipating girls and the way the morning sun

glazed the high windows of the classroom

as though God had become light

and all of us were temporarily haloed

in a kind of celestial brightness that

had I not known better

I might have mistaken for love.

When I Believed

The sun drifts below Mt. Helix,

twilights our beige duplex in La Mesa

where my mother drinks the only beer

I will ever see her drink.

She’s missing my father who’s sailing

toward the edges of the world

this October when the Santa Ana winds

heat the canyons. Mom’s thirsty,

trying to connect with dad,

but halfway through she pours the yeasty brew

into the kitchen sink, throws back her black

hair, which is beautiful, and hangs in thick

bangs down her acne-scarred forehead.

She holds this fragile world

of absence together:

the everyday swirl of school,

dinners of cornbread and pinto beans.

On Saturdays we go to Coronado,

and I collect sand dollars to pay

the light bill, groceries, rent,

and the huge debt we owe Jesus Christ,

our Lord and Savior who redeemed us

to this brittle life of the poor.

On Sunday nights my mother scrubs

my elbows and neck raw

in preparation for Monday.

My skin, like my clothes, will be worn, but clean.

Past a park where the eucalyptus trees are green

with the heavy light of morning,

I will march like a Christian soldier,

the small change of broken

shells rattling in my pocket.

On the Saturday after the Rapture

Tonight my mother will watch the latest hurricane

news and tell my father that surely these are

the “End Times” and the sight of bedraggled

brothers and sisters swimming down streets in New Orleans

or Gulfport or some other god-forsaken-place

where the storm has landed, will further confirm

Revelation, and she’ll fall asleep dreaming

of Apocalypse. The moon was red the other night

and I imagined horses swimming its pockmarked surface

as I walked the dog down our quiet, South Florida street

and felt the first cool breeze of September rush

through the black olive trees to greet me.

The dog and I don’t want the world to end.

We’d prefer not to be burned alive in a nuclear holocaust

or drowned in the storm surge from a tropical cyclone;

in fact, the both of us would prefer to live forever,

and every night after our walks, for eternity, we’d like to head home

for his dog biscuit and my ice cream, respectively,

though it’s true he does like ice cream and I like his Newman’s

peanut butter treats, the crunchy almost sweetness

of the little heart-shaped delights.

I don’t eat his treats often, but I’d like

to dream his running dreams, the ones

that follow our walks when he collapses

on the rug, and then his snout

quivers and his body quickens, legs swimming,

tail whacking the living room floor.

This is the way the dog dreams

and sometimes he whimpers

as though he’s seen a squirrel

in that velvet black world

of strange moons where horses swim

in lunar light and angels whine

after them, wishing god had given

them legs instead of wings

and moons to wander instead of dead constellations.

But those are imagination horses

and the grim angels are real,

their fingers dripping with New Testament blood,

their glowing skulls radiant

like the grinning dead,

the ones god will plow the fields of earth with

on the Saturday after the Rapture.

On the Saturday after the Rapture,

the dog and I would prefer to watch cartoons

instead of being thrown into a lake of fire.

The dog and I would like to eat peanut butter

right out of the jar and watch Bugs Bunny

instead of being tortured forever by Satan,

that grimmest of all angels, the fallen one,

the serpent, the tempter, the all-time worst bad guy

whom the Baptist preachers condemned in showers

of spit, as they thundered about the spitted skewers

that awaited every graceless sinner.

Grace is the horse that runs beneath the moon

on a blue-tinted field outside Lexington, Kentucky

where I lived once in those lonely days before

I met my dog. But I still loved horses,

which the Lakota Sioux called “big dogs”

because they had no name for the escaped

Spanish ponies, the ones that fled Cortez

and Coronado in those long ago days

when the Conquistadors brought Jesus

and salvation on the tip of a bloody sword.

So many died for our God.

No one has died for Dog.

No one has died from preaching horses

running across a red moon, harbinger

of fall when hurricane season will finally end

and those of us still alive will sleep

with our canines on Florida nights

when we forget the stars above us are long dead,

when we forget the story of our own mortality,

that secret which leaks out with every breath,

as we dream hopefully of whole herds of horses

running across fields of full moons, their hooves

kicking up luna dust, the whole universe

awakened by such thunder that

even those angels are afraid.