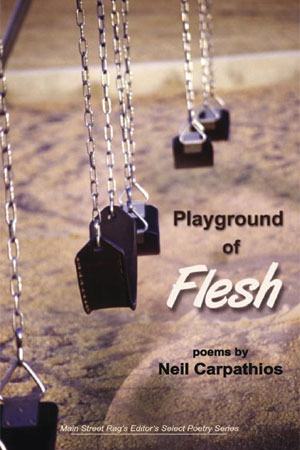

Poems by

Neil Carpathios

Poetry book, 80 pages, cover price $12

($10 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-043-5

Release date: 2006

***This title was selected for publication after finishing as runner up in the 2006 Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award***

Neil Carpathios attended the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and has since lived and worked in Ohio. He has taught creative writing and literature at various universities and currently is a professor at Walsh University in Canton. He also teaches English at Jackson High School in Massillon. His previous collections are: I The Father (Millenium Press), The Weight Of The Heart (Blue Light Press), God’s Experiment (winner of The Ledge competition), Greatest Hits (Pudding House), and In The Womb Of Kisses (Spare Change Press). He has been awarded numerous prizes for his work, most recently a second Individual Artist Fellowship from the Ohio Arts Council and a nomination for a Pushcart Prize.

Neil Carpathios attended the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and has since lived and worked in Ohio. He has taught creative writing and literature at various universities and currently is a professor at Walsh University in Canton. He also teaches English at Jackson High School in Massillon. His previous collections are: I The Father (Millenium Press), The Weight Of The Heart (Blue Light Press), God’s Experiment (winner of The Ledge competition), Greatest Hits (Pudding House), and In The Womb Of Kisses (Spare Change Press). He has been awarded numerous prizes for his work, most recently a second Individual Artist Fellowship from the Ohio Arts Council and a nomination for a Pushcart Prize.

God thinks of all the men and women

He’s created since Eden. He wonders

what went wrong.

It’s about time Sharon Olds met her match. In Playground of Flesh, Neil Carpathios plunges into our primal preoccupations with death and desire with the shocking exuberance of Olds, and his own dark and delicious language. In his compelling visitations to the foul rag and bone shop he’s like the praying mantis who knows the female will eat him, but is “too mad with desire / to stop, even headless.” I can think of few poets who could serve as more reliable guides to the confusing and beautiful terrain of the heart.

–George Bilgere

These are stunning poems. At once philosophical and plainspoken, they walk the line between pain and bliss with unsettling ease. Sometimes humorous, often sexy, they describe the landscape of desire, of what it means to live, and live fully, in the body.

There is a kind of tragic sensibility here, a willingness to see the human vessel as both a cadaver beneath a doctor’s knife and a lover’s paradise. Neil Carpathios finely articulates that which is most sacred, and yet most human. He is nothing short of a master of his craft.

–Nin Andrews

The Smell Of Death

Being a surgeon’s son has perks.

You get familiar with the smell of death

when he walks in after work

scrubbed clean after dicing bodies,

sewing skin. You play detective,

see if you can find the slightest

clue: blood under the nails,

a stain on the sleeve.

You hang on every word

in case he lets slip some scrap,

like “cadaver” or “EKG gone flat.”

When he greets your mother

you watch his hands cup her chin

and guide her face to his to kiss,

same hands you know earlier

sifted someone’s soul like sand

through his fingers in a gaping hole

inside a chest. He hugs you close,

you breathe his daily smell.

You feel his body, your body

pressed, you wonder what swirls

inside like vapor in a jar,

and when he looks at you,

you search the eyes for what

they’ve seen, convinced the smell

of death is Old Spice and sweat.

Playground Of Flesh

Summers home from college I worked

where corpses were kept on steel cots

in crinkly plastic bags. I baby-sat bodies,

assigned each a name and number

for medical students who came in spattered coats

in clots of three around each slab,

unzipped their bag and said hello.

They’d read the tag tied with string to a toe

the name I’d given as carefully as any parent

names a child: Orpheus-80, Galatia-67, Demeter-22 —

names a corpse deserved, I thought,

then with scissors they’d snip skin above the breast

hanging over the corpse’s arm

revealing meat, a neat hole cut for the nipple

which sat

like a cherry on a sundae.

They’d saw ribs the way you would

a log, taking turns, arms tiring,

then pried open the chest

with vice-like screws. Mist shot out —

the corpse’s soul,

or body’s belch of air and heat —

as from an uncorked bottle

of champagne.

Up to their elbows in muck,

like children slopping in mud,

they’d dig out organs, dump in a metal tub.

They’d catalogue each part we pass through

this life with, all of it

sloshing inside our clothes.

I’d imagine spirits of cadavers hovering

near the ceiling, looking down, amused at us

in our playground of flesh. I’d sit in the corner

pretending to read but pictured my head attached

to the bodies, my eyes closed, faking my death

just to have someone’s hands cup my heart

like a prize tomato.

Macho Man

In the lab I remember the baby in the jar

crammed like sausage,

in formaldehyde preserved,

legs and arms twisted, jammed,

hands balled in tiny fists,

feet curled.

Dad got me the job

which sounded better than saying

McDonald’s or cutting lawns

to girls in tight jeans at Joe’s pool hall.

I’d brag, sound matter of fact,

watch their amazement, disgust,

but always respect. I’d tell them

other jars held other things:

a liver, lungs, pancreas, heart.

On shelves lined-up like books,

strange souvenirs the doctors kept,

maybe to remind them their jobs

involved parts of themselves.

I’d say I pour blood into tubes,

cork them with rubber stops,

stick labels with patients’ names.

I’d describe the antiseptic smell,

squeak of shoes on floors scrubbed clean,

doctors inviting me to lunch.

I’d buy the girls beers and call it

a strange museum, which they thought

poetic. Later, making out

behind the hall in my car or pressed up

against bricks, they never knew I sometimes

still saw the little face squinched to the glass

as if trying to see out a window.

Neil Carpathios attended the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and has since lived and worked in Ohio. He has taught creative writing and literature at various universities and currently is a professor at Walsh University in Canton. He also teaches English at Jackson High School in Massillon. His previous collections are: I The Father (Millenium Press), The Weight Of The Heart (Blue Light Press), God’s Experiment (winner of The Ledge competition), Greatest Hits (Pudding House), and In The Womb Of Kisses (Spare Change Press). He has been awarded numerous prizes for his work, most recently a second Individual Artist Fellowship from the Ohio Arts Council and a nomination for a Pushcart Prize.

Neil Carpathios attended the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and has since lived and worked in Ohio. He has taught creative writing and literature at various universities and currently is a professor at Walsh University in Canton. He also teaches English at Jackson High School in Massillon. His previous collections are: I The Father (Millenium Press), The Weight Of The Heart (Blue Light Press), God’s Experiment (winner of The Ledge competition), Greatest Hits (Pudding House), and In The Womb Of Kisses (Spare Change Press). He has been awarded numerous prizes for his work, most recently a second Individual Artist Fellowship from the Ohio Arts Council and a nomination for a Pushcart Prize.