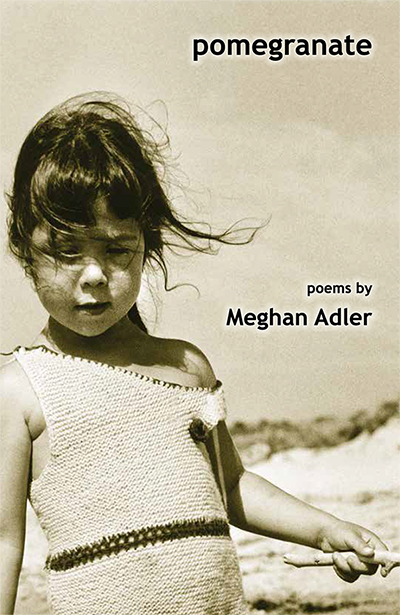

poems by

Meghan Adler

ISBN: 978-1-59948-667-3, ~72 pages, $14

Release Date: March 13, 2018

$14.00

In stock (can be backordered)

poems by

Release Date: March 13, 2018

Meg Adler author portraits

Meghan Adler has been an elementary school educator for over twenty-five years. When not supporting students in the areas of literacy, she can be found at cafès on Valencia Street writing and/or reading poetry. Meghan honed her craft at The Writers Studio in New York, and since then, continues to learn from her favorite poetry teachers in workshops across the globe. Meghan’s award-winning poems can be found in Alimentum, Gastronomica, Lumina, The North American Review, Rattle, and even on an Eric Kent wine bottle.

With vivid details and description, Meghan Adler creates memories of family, lovers, and strangers, making a multi-faceted portrait of a woman’s life. In natural, conversational lines, she invites us in and then carries us deeper. No wonder this book is titled Pomegranate! These poems are full of marvelous food and rich words that are delicious in the mouth. So that by the end, I am, like her, sitting at a blue-flowered tablecloth scattered with sugar/…picking up each sweet crystal,/licking my fingers, one at a time. –Ellen Bass

Fearlessness and loss co-exist in Meghan Adler’s poems; honesty and a keen self-awareness do, too. The precision of autobiographical details—Revlon Red, say, or “the raised seams of jock straps”—takes on the simultaneous weight of elegy and desire. There is much grief in these troubling, witty poems, but also faith, appropriately disabused, in the usefulness of art: “Each day is its own poem.” Pomegranate begins in inquiry—How do you say, gone—and ends, with the hope “to be lifted,” in hope. –Randall Mann

What is the self? What comprises the portrait of the artist? What determines who we are? In her spectacular debut collection, Pomegranate, Meghan Adler draws from childhood memories, romantic relationships, ancestral voices, and poetic precursors in order to create a map of internal and external identities. Through an ingenious deployment of botanical metaphors, Adler’s candid and capacious poems explore the development of a woman and a poet from seed to plant to blossom to fruit. –Dean Rader

For Sarah

After my twin sister and I

fed Rudolph, our red-nosed goldfish, the only

pet our mother wasn’t allergic to, we carried

our matching green and yellow sleeping bags

to the stairs. Between the first and second floor

of newly stained 1860 banisters, freshly hung

blue-beige grass wallpaper, smells of wood polish,

bamboo stalks, and Tide filled the air, we labored,

unzipping our cotton cocoons to form tarps,

securing them with masking tape from the junk drawer.

Finished fort; we splayed out on the stairs

as best we could, dividing our bodies between

levels and layers and read with a flashlight

about Nancy Drew’s secret old clock.

We were happy and warm and together,

while our kind mother and father renovated

the other parts of our house instead of their marriage.

If we had known this was our last summer as a nuclear family,

maybe my sister and I would have taken better care

of that antique wallpaper, before ripping

the tape off too fast, leaving peeled back spots

of raw sheet rock, gray and unadorned.

At a fruit stand, I’m trying to examine a pomegranate: ripe or rotten? And I want to call my dad and ask him to explain everything all over again. Ask him where periwinkles come from. His hands cupping my five-year-old face. Let’s go find their mothers and fathers. I sniff the pomegranate for sweetness. I don’t know what I’m doing anymore. All I really want is to make that new salad I saw on a cooking show last week. Pomegranate, arugula, olive oil, balsamic vinegar, and shredded dried ricotta. He’d know the difference in texture between dried ricotta and Parmigiano-Reggiano. I listen for the pit’s rattle. But it was the avocado he said to shake. I fish for one that isn’t too soft. A clear red without mold or bruises. I close my eyes and hear my dad: pick before overly ripe, before they crack open, especially if they’ve been rained on. Warm the fruit by rolling it between your hands to soften the insides, to ready the juice of the seeds.

I wanted to be blind.

Like Mary Ingalls,

tracing the bamboo

wallpaper of my childhood

home,

looking for doors

opening

and Sarah’s hand.

We used to practice

being Mary,

while the other

one played

the Annie Sullivan-type,

guarding against wobbling

lamps, couches or the sharp edges

of coffee tables.

I want to smoke again.

Take my No. 2 yellowed

Dixon Ticonderoga

and inhale deeply

and slowly and share it

with Sarah.

We blew invisible

smoke rings, like Lady Penelope,

the marionette, on “The Thunderbirds.”

Sitting in our makeshift

pink convertible Rolls Royce,

batting our royal eyelashes slowly,

as only a puppet can,

tossing our long blonde hair

from side-to-side, adjusting

our pearl necklaces as big as marshmallows,

and saying in our best

British accents

to our driver, Pahker,

Drive. Drive.

Astoria, Queens

Wednesday and the old Greek men are at it again,

arguing about recycling with the garbage collectors.

Giati? Giati? Why? Why? Do cardboard boxes still need

to be tied up with strings? When the truck leaves,

these white-haired men go back to brooms

and sweep their sidewalk slabs before frappé me gala

and tavli. Widows sit at windows, peek from behind

their history of lace curtains, watching commuters

make their way to the N train. And there’s Nikko,

the teenage neighbor who struts to school with too much

hair gel, the one who sits outside in lime green beach

chairs with his near-deaf uncle on Sundays, concrete

driveway, their handheld radio reverberating soccer scores

and Greek news. Nikko spits sunflower seeds at the ivy.

His messenger bag slumped over his back, the way

it was for his grandfather from Ithaca–shepherd on donkey–

going to herd his sheep, carrying his meal in a sack.

iPod and black sunglasses, Nikko suddenly stops

as he passes Saint Constantine and Helen, glances up

at the stained glass, beveled and blue, soot on sills.

He sees the church steeple, copper and green, reflect sunrise,

then crosses himself three times. His lips moving slightly,

The son of the Father. The son of the Father. Estonama tu Patros.

Mist is rising, morning fog drying, and the wind is right.