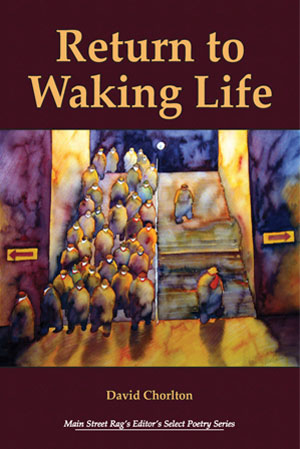

poems by

David Chorlton

Poetry book, 110 pages, cover price $11

($9 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-93090-744-7

Release date: 2004

The Dispossessed

You don’t have to know that David Chorlton was not born in the United States to sense his feeling of unease and of being a stranger in a strange land. It’s in his poetry. Certainly it’s in Return to Waking Life. This sense of alienation appears, for example, in his choice of nouns—foreigner, refugee, alien, immigrant, borders, frontier, identity. The poet doesn’t feel at home here. He tells us This is someone else’s country. He feels an alien/among aliens. The time has come, he says, to be the foreigner/you never expected to be. Indeed, he expected to feel more comfortable, more at home, but he hasn’t given up: I’m still trying/to find my place.

When one feels somewhat out of place, one longs to return home. The poet is fully aware of Wolfe’s warning that you can’t go home again—Don’t go back, a voice repeats. But he can’t help himself. He goes home, and, of course, it isn’t home anymore. He calls it a trap—a tempting and seductive trap. Everything has changed. And he quickly learns the things we miss once they disappear/were never beautiful, only familiar.

But if you can’t go home again, you need to escape somewhere. That sense of alienation drives the wish to be someone or something else. Because of his feeling of not belonging, he struggles to escape, just as we all do. He senses that he is not alone with these feelings, that nobody wants to be themselves anymore. We want to be someone else. We may try disguise, we dress as someone else, or when our identity is stolen, we might even find that suddenly we feel lighter.

Because of Chorlton’s affinity with wildlife, he fantasizes about their lives, how at home they seem in the world. To become an animal would be appealing, and in “Metamorphosis” he turns himself into a beetle, a moth, frog, deer, nightjar, snake, lion, and coyote. In other poems he becomes invisible, or tries escaping through nostalgia, reading, writing, dreaming, or music. Of all these, music seems the most satisfying, while writing seems the most difficult.

The poet’s state of residence, Arizona, is, of course, a state of newcomers, of the dispossessed, of immigrants. Except for the Native Americans, Arizonans are all refugees from colder places, so these lessons and the struggle to feel at home in a foreign world, are not just the poet’s. He shows us the steps of what he calls acclimatization—how newcomers try to make adjustments until our first countries fade. But does it ever happen? Although we do our best to fit in, Chorlton asks, can we ever feel at home in our country? in our city? or even in our bodies?

Chorlton tells us he has been here twenty-five years, and sees more of himself—like the animals of the Southwest—disappearing into the desert. Even so, people tell him that if he doesn’t like it here, he should go back to where he came from. To that, he responds, You tell me/ I ought to be happy/in the greatest country ever, or leave it/but where else can I live two lives at once/where else is the taste of not belonging /quite so spicy on an alien tongue?

It is the sense of not belonging that gives us, or at least gives the poet, the ability to see both homes with fresh eyes, to give the rest of us insight into how we behave, how we might not be living up to our own standards of the greatest country ever. We are grateful that David Chorlton, like Alexis de Tocqueville and others before him, can give us these lessons. It is his taste of not belonging that gives him and us the spice that can zap us out of our too comfortable, too self-satisfied, complacent lives. We are grateful that he shares with us his sense of being one of the dispossessed.

John Spaulding

David Chorlton lives in Phoenix, where the surrounding landscape still surprises and delights him after twenty-seven years in Arizona. He divides his working time between writing and painting, and is occasionally featured in performances of genres outside poetry, combining his reading with music. Manchester, England, was his childhood home, which he left in 1971 to live in Austria, his birth-country. Vienna’s impression remains a strong one, as does that of the many travels David took during his seven years of living in central Europe. Having left school in Manchester at age sixteen without having had an introduction to contemporary poetry, he caught up by reading in later life. After a year or two in this country, he began to publish in American small press magazines and continues to lead a life made interesting courtesy of the US Postal Service. Collections include a number of chapbooks, including winners of competitions at Main Street Rag, Slipstream, Pudding House Publications, and Palanquin Press, and the books: Forget the Country You Came From; Outposts; and more recently, A Normal Day Amazes Us from Kings Estate Press. Away from poetry, David and his wife enjoy hiking, birding, music ranging from medieval to modern, and out-of-the-way movies.

David Chorlton lives in Phoenix, where the surrounding landscape still surprises and delights him after twenty-seven years in Arizona. He divides his working time between writing and painting, and is occasionally featured in performances of genres outside poetry, combining his reading with music. Manchester, England, was his childhood home, which he left in 1971 to live in Austria, his birth-country. Vienna’s impression remains a strong one, as does that of the many travels David took during his seven years of living in central Europe. Having left school in Manchester at age sixteen without having had an introduction to contemporary poetry, he caught up by reading in later life. After a year or two in this country, he began to publish in American small press magazines and continues to lead a life made interesting courtesy of the US Postal Service. Collections include a number of chapbooks, including winners of competitions at Main Street Rag, Slipstream, Pudding House Publications, and Palanquin Press, and the books: Forget the Country You Came From; Outposts; and more recently, A Normal Day Amazes Us from Kings Estate Press. Away from poetry, David and his wife enjoy hiking, birding, music ranging from medieval to modern, and out-of-the-way movies.