poems by

Joyce Compton Brown

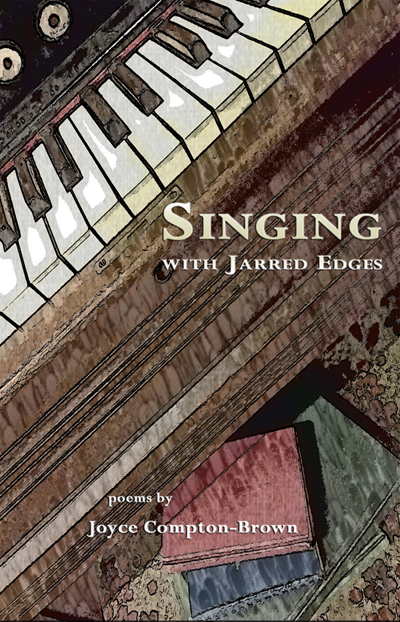

ISBN: 9781-59948-675-8, 52 pages, $12

Release Date: April 24, 2018

$12.00

poems by

ISBN: 9781-59948-675-8, 52 pages, $12

Release Date: April 24, 2018

Joyce Compton Brown, featured poet at the 2016 Doris Betts Literary Festival, has published numerous essays, reviews, poems, and the chapbook Bequest (2015, Finishing Line Press). She taught literature and writing at Gardner-Webb University after earning degrees in literature from Appalachian State University and the University of Southern Mississippi. She studied poetry at Hindman Institute and Appalachian history and literature at Berea College then wrote a humor column for the Shelby Star, Cleveland County, NC, before returning to her roots in Iredell County, where she continues her lifelong interests in painting, music, and the banjo, purely for the pleasure.

Joyce Compton Brown’s wonderful new collection of poems could literally have been sung into being, filled with homespun eloquence and wisdom and all kinds of mountain music , from famous North Carolina balladeer Bobby McMillan singing “Fair Eleanor;” to Elvis Presley singing Big Boy Crudup; to hometown parade marches; to Doc Watson’s vision that brought us the annual music festival Merlefest; to the “long blue hymns” and modal tunes at Pleasant Hill Baptist Church; to “The Patient Sings the Surgeon Fixed It Blues,” based on Steve Earle’s “Oxycontin Blues;” to Lula Belle singing “Amazing Grace” at the Franklin Reunion…….and if a poem hasn’t got a song in it, it’s got a whole novel! Entire lives are captured in such poems as “The Town Spinster Becomes a Piano Teacher,” the yearning “Blue Ridge Parkway 1938,” and the short, heartbreaking “Mr. Coffey Plays His Banjo in His Warm Boone Apartment.” “Fourth Grade Civics Lesson” is a perfect coming-of-age short story. Visual, melodic, character-driven, Joyce Brown’s extraordinary poems literally leap off the page. –Lee Smith

Music abounds in Joyce Compton Brown’s Singing with Jarred Edges, from the “long sad songs / of the welcoming elect” of the Pleasant Hill Primitive Baptist Church—mysteriously weaving their ancient spells of communal inclusion and exclusion—to the sad, celebratory fraternal “String Music at the Old Place,” to that necessary character in the cast of every small Southern town—the inescapable spinster piano teacher—on to Elvis, Arthur Crudup, Jim Morrison and The Doors, winding back to ballad singer Bobby McMillan, The Toe River Boys, Mr. Coffey and his banjo playing for his life in Boone, and finally reaching its destination with the legacy of Doc Watson and family in Wilkes County, “all the singing / roiling far beyond the / mountain’s ridge.” Other poems, like “Blue Ridge Parkway, 1938” and “Railroad Dirge,” take us on other kinds of journeys—the panoramic Americana of the 1930’s WPA and CCC and, earlier, the mountains, mill towns, and immigrant laborers of the westward expansion by rail. James Agee, in his incandescent Prologue to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, at one point wishes his book contained “no writing at all”: “It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and excrement.” Despite that documentary impulse to physicality, Agee knew his book had to be made of words, and so does Joyce Compton Brown, thankfully, because this collection confirms her to be a master artisan in that medium, despite its limitations and frustrations. Brown has succeeded admirably in her quest of “calling forth a living past, / giving strength for the present, / making bearable all thoughts / of the future.” If you are lucky enough to read this book, you will be in her debt. —Jim Clark

At Uncle Morrison’s funeral

cousin Henry sang Hark Ten

Thousand Harps and Voices

in the way of our parents,

flat and high and strong,

rolling each note like a marble

calling forth reunion memories:

fried chicken and chocolate pie,

cold Nu-Grapes in glass bottles

nestled in hissing dry ice,

sweet tea, pesky yellow jackets,

sweaty August Saturdays,

reverent cemetery strolls,

pauses at the strange-familiar

names of our family dead

calling my mother’s face to life,

proud of children who knew their place,

calling forth my old imaginings,

my mother as a dark-haired small girl

standing at a wood wall blackboard

in a shining white one-room school,

warming small cold hands

by the cast-iron stove, pleased

by spelling bee triumphs, glowing

with victory, a child who smiled

free of pain, as I never knew her

We were enamel children then,

danced to teen angel’s bloody death,

wept Oh Donna with Ritchie Valens,

sated our souls with vicarious kisses

from pretty boys humming on the radio.

That’s alright now, Mama. We shifted

away from boys with ducktails

and never wore pink and black

nor moved with undulating hips.

Anyway you do. We were Dixie

Girls in circle skirts and certain

bounds. Those tracks pierced

the town center shining neon

and we did not wish to cross

into the darkness

of our parents’ hearts.

Go fly, go ahead and fly

Till you find out who you are.

—Billy Dean, Somewhere in My Broken Heart

Oh, when the black diesel cloud above Bobby Joe

Denton’s beloved “Deuce is Wild” modified stock

tractor spouted roiled and trailed dark soot into

the grey-streaked sky,

And when Frank Brawley moved the massive Skoal-flagged sled

with a mighty heave of his “Carolinian” unlimited class truck

and the headers on his Allison engine shot cool alcohol flames

into the dusk-rose night,

And the green John Deeres silently smoothed the glowing

red clay track while Billy Dean blessed two thousand souls

at peace on a sloping lawn with his hope that they might find

what they longed for,

And the white moon pierced the smoky night and glimmered

again from the perfect mirror of the oval lake while sweet

young girls twined glowing blue and green halos in their hair

so bluejeaned boys might ache,

And children flung neon golden lights into the gloom

and did not cry in their darkness while the country

twang of Billy cried out for what was lost somewhere

in his broken heart,

So that sleep-eyed boys and babies and men with callused

hands and new mothers in grass-stained lawn chairs

and burnt-faced drivers of big trucks might hear

and be comforted,

And you and I ate our ketchuped fries and smiled our distant

smiles and found the wonder of a sweltering July night

on a grassy hill under a charcoal sky above a red clay track

beside a moon-glow lake.