Something is Bound to Break

poems by

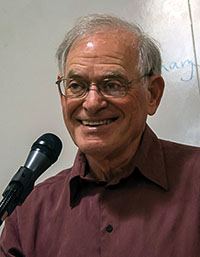

Peter Neil Carroll

ISBN: 978-1-59948-766-3, 100 pages, $15 (+ shipping)

Projected Release Date: October 1, 2019

Peter Neil Carroll has published over twenty books, including five previous collections of poetry: An Elegy for Lovers (Main Street Rag, 2017); The Truth Lies on Earth; Fracking Dakota: Poems for a Wounded Land; A Child Turns Back to Wave: Poetry of Lost Places which won the Prize Americana; and Riverborne: A Mississippi Requiem. His poetry has appeared in many journals and online. He is also author of the memoir, Keeping Time: Memory, Nostalgia & the Art of History. He is currently Poetry Moderator for Portside.org and lives in Northern California with writer/photographer Jeannette Ferrary.

Peter Neil Carroll has published over twenty books, including five previous collections of poetry: An Elegy for Lovers (Main Street Rag, 2017); The Truth Lies on Earth; Fracking Dakota: Poems for a Wounded Land; A Child Turns Back to Wave: Poetry of Lost Places which won the Prize Americana; and Riverborne: A Mississippi Requiem. His poetry has appeared in many journals and online. He is also author of the memoir, Keeping Time: Memory, Nostalgia & the Art of History. He is currently Poetry Moderator for Portside.org and lives in Northern California with writer/photographer Jeannette Ferrary.

There is no subject too large for Peter Carroll, a strong and unusual poet who writes with intelligence, with certainty, with wisdom, and with a strong and compelling voice. The poems in this collection are worth reading again and again. ~Esther Cohen, Breakfast with Allen Ginsberg

Poetry is hard. Consider the world we live in, consider these magnificent poems by Peter Neil Carroll. I admire his courage to tackle the intimate and the distant. I admire the way his poems hunger after words without being self-indulgent or over-the-top. His language is vivid and specific and sensory and intelligent. These are poems of beautiful precision, deep seeing and knowing, rhythm and music and song and singing. ~Joseph Zaccardi

Something’s Bound to Break, Peter Carroll’s most personal book to date, offers us a writer at the peak of his powers. In episodes from a long, eventful life he portrays the human condition in all its grandeur and folly. Childhood, romance, the phantasmagoric maze of New York City, everything that touches him becomes an opportunity for wisdom. Something’s Bound to Break will leave you laughing, enlightened and asking for more. ~Lee Rossi

The CEO Speaks

When the customs officer at Newark

pulled me aside to ask what I do, I told him

I’m a poet. You write jingles? he replied.

Luckily, I live with a sensible woman who

has a real job at a Silicon Valley company

producing high-tech heat-shrinkable plastics.

She brings me to my first corporate Christmas

party, not-quite bald men clutching drinks

and blond-dyed secretaries sniffing champagne.

Already the big shots are working out whom

to bed when the party runs dry, before they

retreat to their wives raising virtual children.

Unsure of my welcome, I keep to the edges, mind

my business, which is to say take mental notes

for a poem I will write someday on male privilege

until one of the suits notices me standing alone,

approaches with a handshake. Quickly I explain

my ticket of admission and he scans the room

to find the woman I live with. She’s from Brooklyn,

he tells me, as if I didn’t know, which is his own

home town and goes on to relate his rags-to-riches

spiel. He is affable. I take a chance and ask what

he does. He smiles, he winks, enjoying the question,

concedes he’s CEO of this Fortune 500 business.

What about you, he gets around to asking, amused

as if he knows the answer. A poet I admit. His eyes

narrow, measuring carefully. That’s what’s great

about America, he says, invoking his wisdom, you

can be anything you want—an opera singer, an artist,

a poet—as long as you don’t expect to be paid for it.

Finance

Maybe because my father fixed

pocket watches and antique clocks

I never carry a timepiece.

The one watch I cherish

belonged to my mother’s father,

a gold stemwinder attached

to a chain that he held close

to my face, springing open the lid

to bump my nose.

That watch has ancestral history

not for its age or rarity

but how my grandpa used it

for so much more than telling

the time. A glazier in New York

who earned $5 a week for six days

of labor, he had no means to pay

the fare to bring his wife (my grandma)

from Minsk. Obviously he could not

afford a gold watch. But he bought this one

on the installment plan for 50 cents down

and quickly pawned the watch for $50

to cover grandma’s passage. Afterwards

he kept up the payments and managed

to redeem the pawn. Whereupon grandma

announced she wanted to return to Minsk

unless he brought her parents to America,

prompting him to refinance the watch.

But for that delicate object, the only thing

of value he ever owned besides his tools,

he would have been another lonely immigrant

in a lonely city

and I would be nothing at all.

American Dream

Shouldering window glass, an unlit

cigarette in his lips,

a youth enters a side street,

Minsk, 1904.

The aproned shop girl Mata

watches him pass. He doesn’t know

yet but in time he’ll marry her

and in more time

become my grandpa.

Minsk, another stop on his road.

The itinerant glazier stays, he says,

for Mata’s cooking and the revolution.

But when he’s nearly killed

at a protest meeting, he leaves

immediately for the promised land.

Poor then and ever after,

stealing ship’s food, he arrives

in New York, marvels at insatiable skyscrapers,

their greed for glass. His trade lives

in his hands, his skin split from splinters,

bones shattered by faulty ladders.

What he found in America he told

ever after, his recurring dream—awakening

inside a vault filled with pennies—stuffing

his pockets—entering another room piled

with nickels—leaving behind pennies,

taking nickels, then with dimes in the next room,

reaching quarters, dumping again, re-filling—

then, he says, I woke up with empty pockets.