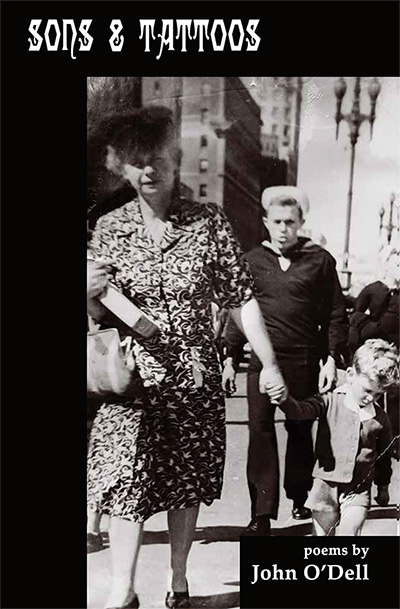

Sons & Tattoos

poems by

John O’Dell

ISBN: 978-1-59948-861-5, 44 pages, $12 (+ shipping)

Projected Release Date: February 23, 2021

The Advance Sale Discount price of $8 expired February 1. For those who prefer to not buy online, the check price is now $16/book (which includes shipping) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, PO BOX 690100, Charlotte, NC 28227-7001.

John O’Dell’s parents, an Australian school teacher and an American sailor, landed him in Sydney in 1942, gave him a kid’s Midwest farm, and L.A., Berkeley, before a seven year 70’s stint of country school teaching in Australia, again. Now, in Maryland, his work has appeared in The Potomac Review, The Baltimore Review, The Birmingham Poetry Review and in several anthologies, Free state: A Harvest of Maryland Poets, and Hungry As We Are, and Meridian’s Anthology of Contemporary Poetry. He has two books of poetry, Painting At Night (Little Cove Press, 1994) and At Beauty’s Pawnshop (Ex-Libris, 2013).

Sons and Tattoos is a Lyrical Narrative — stories about characters and situations with reverence for a beautiful lilt in language. These lived experiences show a respect for the past— its heart’s wounds— and a passion for how art restores the world. O’Dell speaks of “mind’s hunger for pattern and line.” This poetry connects vibrantly and directly with the truth; I love these poems and I believe them. ~Grace Cavalieri, Maryland Poet Laureate

The poems in John O’Dell’s Sons and Tattoos, with their strong Anglo-Saxon sounds, feel as if carved from stone. The poet’s voice here is deeply, often achingly intelligent, the emotion tempered by hard-earned wisdom. O’Dell has crafted his inheritance into a collection that combines the weight of history and the feel of myth. This is a stunning sequence of poems. ~Rose Solari, author of The Last Girl (poetry) and A Secret Woman (novel)

They Always Wore Hats

They always wore hats, the men

of my grandfather’s generation,

or, so say, the four photos of him

that survive; fifty year old black

and whites, Charles Miller,

fleeing the Prussian soldier Bismarck

would make of him, landed

in Sydney Harbour, looking backwards,

like most others, reassured, yet

troubled by the empty ocean at his back.

He had an impulse toward husbandry.

In these photos he holds wrigglers—

a cat, a child, a barefoot squirmer,

a thumb sucker. The earliest is

taken in the bush, huge hands grasp

hips standing before a starving cow,

a saddled horse in a half cleared

paddock, the horse all but faded

from the photo, now, as the droughts

would later airbrush them all from the

landscape of gum tree and burned grass.

Coal made him wealthy in the city,

and, after his wife died in the thirties

he sailed the world. In China, saw a man

executed, beheaded, I’m told, but

not why he stood in the crowded street

watching, or if it was good schooling

for his own leaving, a sudden heart

attack in a busy Sydney street, life

severed as cleanly as the keen

morning light by the brim of his hat.

The Seaman’s Wallet

Who was he? The wallet answers: #530836.

Issued by the Department of Commerce,

its rivet studded, brown leather cover

shows a ship with twin stacks, pennants

flying, and from each sloping funnel curls

not smoke, but a sharply etched question mark.

A Tattooed rose bloomed on his left forearm.

He had cholera and typhoid shots, weighed

170 lbs., was a serious man. In his passport

photo, a fountain pen bulges in his coat pocket.

A wiper, an oiler, he carried sweat and diesel

in his canvas duffel, with a discharge

from “The Marine Devil”. In Boston, San Diego,

or Sydney, he looked for or left “The James

D. Trask”, “The Pawnee Rock”. War’s tide bore

him to us; its commerce Shanghai’d him away.

The tandem question: when would he return?

We learned it was to be with the others,

the fighting finished, to plant corn, thresh wheat,

bale sweet alfalfa, stack it till a roof,

a barely closed hayloft door allowed no more.

He farmed and found out what he’d missed

by running away from hay. The furrows,

his tractor’s wake, he ploughed, spring and fall,

till earth closed over all, and now laps

patiently against memory’s stubborn stones.

At Lightning Ridge

I awaken to the throb of generators,

splash of a lime tree, a lone plane’s

breast stroke thrust of wings overhead,

wide dirt streets, jumble of wire

and pipe, the rusted husks of cars,

squat, sun bleached houses.

Everywhere igloo mounds of white dirt

speak of hope or dull, stubborn habit.

In the afternoon I watch Sandee nurse

her baby as she takes a tobacco tin

from the back pocket of ragged cutoffs,

holds out opals, each glowing softly

behind a thin membrane of plastic.

At night I see the aboriginal kids

at the café, leaning against pinball machines,

moths drawn to the boxed white fella

lightning, mirror to the dance of insect

and streetlamp outside.