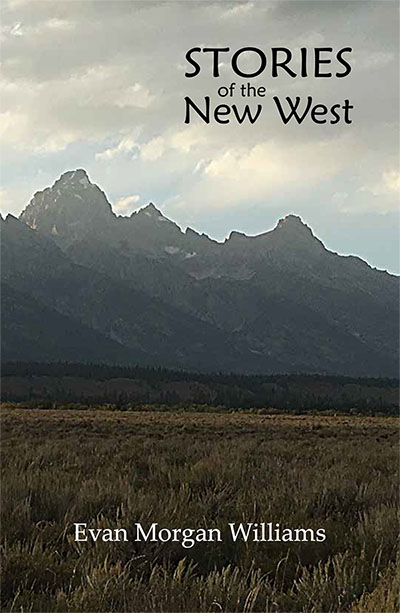

Stories of the New West

short stories by

Evan Morgan Williams

ISBN: 978-1-59948-866-0, 154 pages, $16.95 (+ shipping)

Projected Release Date: September 15, 2021

The Advance Sale Discount price has expired. For those who prefer to pay by check, the price is $$21/book (which includes shipping) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, PO BOX 690100, Charlotte, NC 28227-7001.

Evan Morgan Williams has published over fifty short stories in literary magazines famous and obscure. His first collection, Thorn, won 2013 Chandra Prize at BkMk Press (University of Missouri-Kansas City). The book went on to win a gold medal from the Independent Publishers Book Awards. In 2018, Williams released a second collection, Canyons | Older Stories, in a limited print run. The book won a gold medal from the Next Generation Independent Book Awards. Stories of the New West is his third collection.

Evan Morgan Williams has published over fifty short stories in literary magazines famous and obscure. His first collection, Thorn, won 2013 Chandra Prize at BkMk Press (University of Missouri-Kansas City). The book went on to win a gold medal from the Independent Publishers Book Awards. In 2018, Williams released a second collection, Canyons | Older Stories, in a limited print run. The book won a gold medal from the Next Generation Independent Book Awards. Stories of the New West is his third collection.

In his third collection, Stories of the New West, Evan Morgan Williams covers elemental ground, mountains and deserts, cringe-worthy adolescent humiliation, sad adult failure, the lives of so-called refugees, so-called locals, creating a world of rogues who insist on making their own way, all the while yelling, “Hell no!” and throwing precious gifts into the fire, into the river, into the sky. ~Mary Rechner, author of the story collection Nine Simple Patterns for Complicated Women and the novella The Opposite of Wow

In American mythology, the West may be the Promised Land, but in his latest collection, Williams scratches the surface of this myth to reveal the rust beneath the promise. With his gift for ratcheting tension in all that’s unspoken, Williams’ characters discover the milk and honey of the New West are just fumbled confessions and irrevocable mistakes as they do their best to survive terrains—inside and out—at turns hideous and holy. ~Armin Tolentino, author of We Meant to Bring It Home Alive

DINOSAUR BONES

My dad was a Montana dreamer who amounted to nothing, but I’ll grant him this: he dreamed big. Give him a pail of lemons, and he’d make the usual lemonade, but then he’d plant lemon trees in the wet clay along the Yellowstone, confident they would thrive and shake off winter snow the way a dog shakes off rain. I was not a dreamer, and by the time I turned seventeen—an age when my dad claimed to have driven a semi-truck, tamed a mustang, and laid a college girl—I was living with my mom in California and contending with realities that discouraged me.

Gazing in the mirror, I saw a skinny kid with freckles and pale paper skin. I had never kissed a girl. My surfboard hung in the garage, never used, because I couldn’t swim. My friends and I smoked a ton of pot, if you call that contending with anything, and, because it was easier than facing our failures, we ridiculed the things we cared about most: girls. One secret stayed safe in my heart—I loved the neighbor girl, Samarprat, a black-eyed Indian with a long, glossy braid, golden bracelets and rings, and a pink sari that shimmered as she stood at the bus stop, her algebra book clutched to her chest, her eyes catching mine before gazing firmly away. Maybe she loved me, too. Maybe she longed for me to ask her to a movie with a happy ending, but I could never be sure, and whenever I was with her, I could think up no words to utter without disgracing myself. Once per week, we did algebra homework at her kitchen counter, and I silently balanced equations, my mechanical pencil jittering on the grid paper, while Samarprat set her stool so close to mine that I felt the press and warmth of her thigh.

I never fed that detail to my friends, but my dad would have told everything, including the moment when he made his move. I didn’t even have a move. He would have lured her into the sack, her orderly black braid unraveling over her shoulder. I had lived away from my dad for years, but his stories, his golden-tinsel dreams, haunted me. He dreamed big, he dreamed spectacular, and I can still see him standing on the Montana prairie, solid in the eddying heat, his arms spread wide because he dreamed as big as the sky. His arms held nothing, but to a boy who couldn’t dream up a day’s worth of happiness, his arms held everything I could never attain.

My mom was not a dreamer. When I was nine, after the bank had auctioned off the monorail cars, the eight-track recording studio, and the herd of vicuña, my mom and I left for California. She remarried solidly—my stepdad was reliable and kind—and I lived eight years in a ranch house in San Jose that looked like any other. My life consisted of lying in the sun beside a swimming pool I never used, gazing at the California sky, and listening to garbled water from the koi pond on Samarprat’s side of the fence. Sometimes Samarprat came over to swim, and, when she was done, she lay on a towel in the grass, where she wrote in her diary while I lay on my own towel, dry, smoking bowl after bowl of Columbian gold. Samarprat was a dreamer; she scribed long pages no one was allowed to see. As her hair dried in the sun, strands spilled around her face, around her diary, until she was veiled in a private, shimmering space, and I was alone, watching her, ashamed to dream anything at all.

I still spent a month of every summer at my dad’s farm on the Yellowstone River, and I was glad to go. Come July, I would leave the friends I couldn’t rely on, I would leave the mirror’s unflattering assessment, and I would leave the lovely girl I was too terrified to talk to. These things I would trade for my dad’s stock of amazing stories: mustangs, wildfires, the tractor he drove at seven (the thick Sears catalog upon the seat), kisses from sugarbeet queens, trout the size of New York steaks, flash-floods that left him penniless, fights in bars that left his nose smashed. My dad was a hero with two missing fingers, a rogue with a stent in his coronary artery and a case of TNT in the barn. He was a Charlie Russell painting made real. If his stories strained believability, if his stories rang true only when they ended in failure after failure, his words nevertheless had the solid heft of river stones.

One story stands out: when my dad was twelve years old, running down a loose horse—for which he’d get a whipping—he stumbled upon a complete dinosaur skeleton on the Yellowstone floodplain. A tyrannosaurus rex, a hundred bones or more, the ribs casting twilight shadows; it lay in the mud, bones arrayed as perfectly as a table setting. My dad ran home to tell his parents, but by then it was dark, and although the family lugged every wheelbarrow it owned, my dad was unable to find the skeleton a second time. They trudged home to a pot-roast on the table, cooling into something dry and hard. My dad got a whipping all right. His brothers called him dumb-ass. The stray horse wandered home the next morning.

The day before I left for Montana, I was packing in my bedroom. With money from my seventeenth birthday I had secured a fat wad of dope, and I was debating where to stash it in my duffel bag. Just then, I heard the sound of a hammer. I looked out the window: a realtor in a blue sedan had pulled up, and he was planting a for-sale sign on Samarprat’s lawn. She might be gone before I returned. I might never see her again.

Desperate, I rummaged a card from my mom’s desk and took it to Samarprat. Perhaps the finality of that for-sale sign made it safe for me to approach her at last. I strode up her walk, fidgeting with the card, a photograph of a sunset that looked like fire. I knocked. Through the screen door I could see Samarprat sitting at the table. She was writing in her diary. She waved me in, her black eyes uncertain. I handed her the card, but my fingers fumbled, and the card fell open on the floor. Picking it up, I wanted to crawl under the table and hide: I had forgotten to write anything.

I fled home and finished packing my bag, but I didn’t pack much. My dad’s fantastic life would be the proxy for my empty one.

If you would like to read more of this story and others

by Evan Morgan Williams, order Stories of the New West

Evan Morgan Williams has published over fifty short stories in literary magazines famous and obscure. His first collection, Thorn, won 2013 Chandra Prize at BkMk Press (University of Missouri-Kansas City). The book went on to win a gold medal from the Independent Publishers Book Awards. In 2018, Williams released a second collection, Canyons | Older Stories, in a limited print run. The book won a gold medal from the Next Generation Independent Book Awards. Stories of the New West is his third collection.

Evan Morgan Williams has published over fifty short stories in literary magazines famous and obscure. His first collection, Thorn, won 2013 Chandra Prize at BkMk Press (University of Missouri-Kansas City). The book went on to win a gold medal from the Independent Publishers Book Awards. In 2018, Williams released a second collection, Canyons | Older Stories, in a limited print run. The book won a gold medal from the Next Generation Independent Book Awards. Stories of the New West is his third collection.