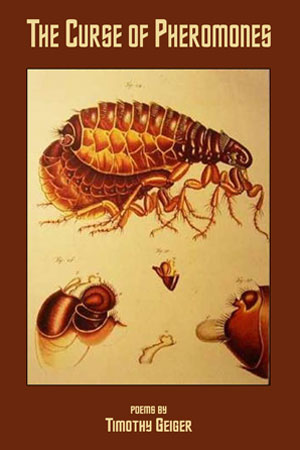

poems by

Timothy Geiger

Poetry book, 64 pages, cover price $14

($10 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-136-4

Release date: 2008

$14.00 Original price was: $14.00.$10.00Current price is: $10.00.

poems by

Poetry book, 64 pages, cover price $14

($10 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-59948-136-4

Timothy Geiger is the author of the poetry collection Blue Light Factory (Spoon River Poetry Press,1999) and seven chapbooks, most recently, Four Windows (Brandenburg Press, 2006). His work has appeared in such journals as Poetry, America, Quarterly West, Poet Lore, Black Warrior Review, The Connecticut Review, Mid-American Review, Artful Dodge, The Journal, & Passages North, and in the anthologies American Poetry: Next Generation, (CMU Press, 2000), Place of Passage, (Storyline Press, 2000), and A Fine Excess: Contemporary Writers at Play, (Sarabande Books, 2000). He is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize XVII, a Holt, Rinehart and Winston Award, and many state and local grants in Alabama, Minnesota and Ohio. He is the proprietor of the literary fine-press Aureole Press at the University of Toledo, where he teaches poetry writing and letterpress printing. He lives in Toledo, Ohio with his wife and son, Jennifer and Jacob.

Timothy Geiger is the author of the poetry collection Blue Light Factory (Spoon River Poetry Press,1999) and seven chapbooks, most recently, Four Windows (Brandenburg Press, 2006). His work has appeared in such journals as Poetry, America, Quarterly West, Poet Lore, Black Warrior Review, The Connecticut Review, Mid-American Review, Artful Dodge, The Journal, & Passages North, and in the anthologies American Poetry: Next Generation, (CMU Press, 2000), Place of Passage, (Storyline Press, 2000), and A Fine Excess: Contemporary Writers at Play, (Sarabande Books, 2000). He is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize XVII, a Holt, Rinehart and Winston Award, and many state and local grants in Alabama, Minnesota and Ohio. He is the proprietor of the literary fine-press Aureole Press at the University of Toledo, where he teaches poetry writing and letterpress printing. He lives in Toledo, Ohio with his wife and son, Jennifer and Jacob.

Even not knowing his poem “Against Theory,” a reader would recognize that Timothy Geiger as poet writes without concern for the fashions of the day. He’s his own man. Such integrity accounts for much of the pleasures his poems offer, and even informs his use of language, which he wields with both authority and a fine touch as in poem after poem he investigates the Self in the World, probing his subject, laying it bare, and naming his discoveries. In that investigation he ranges from supermarket checkout lines to the far reaches of space, from a father and son’s difficult relationship to the nature of time itself. Such range is accompanied by an important balance: human misery is present here alongside the poet’s determination to celebrate whatever he can. In fact, his celebration of the word “aquamarine” is enough to inspire complete trust in him as a poet–other poets may mumble or shout, but Geiger is a singer, and a good story-teller as well, richly imaginative. The question in one poem, “What if heaven plans to judge us / by how we live in our dreams?” would grace Neruda’s Book of Questions and is a measure of Geiger’s imagination. Nor is it surprising that in another poem he tells us he wants to “leave / the humbug behind,” adding, “this is how to survive,” for on page after page in The Curse of Pheromones, a book that is a blessing rather than a curse, Geiger leaves the humbug behind and reminds us how to survive.

–Philip Dacey

What’s the Big Idea? For Timothy Geiger it’s Love and Death and the Divinity behind each-and the abiding belief that we mortals, even as we get clobbered by that Divine, are charged to make art of it. I stand in awe of Geiger’s wonder, faith, and poetic range. The work in Geiger’s long-awaited second full-length collection is honest, thoughtful work crafted by a poet very much alive in his own questioning.

–Kathy Fagan

The Curse of Pheromones is a rich, funny, deeply moving collection. There’s a refreshing humility and innocence in these poems that brings back a sense of wonder at the things of this world-that tenuous sense of wonder we take for granted until it is gone. Timothy Geiger is a poet of great clarity and sincerity. His feet are on the ground, but he’s looking up at the sky. These poems allow us to stand there next to him in awe and amazement.

–Jim Daniels

BELIEVE

What makes you think

you’ll be anything else

when you’re done with this body?

Does any other creature on earth ask this,

or tremble in fear from it,

or lie back, shoulder-bones to wet grass,

look up at the moonless sky and wonder

anything other

than the nearest source of heat?

The field-mouse and the gull

don’t pin their hopes on salvation,

just the stray crumb and an overlooked seed.

The wild-flowers would bloom

year round if they could

they’d bloom themselves out of existence.

Why is it that what you’re allowed

is never enough? Doesn’t the song change

with every pitch and rhyme?

And why, after all this time listening,

are you still sitting there

when you’ve so much left to do?

THE LAST THING I TAUGHT THE DEAD KID

He appears

as a ghost

in the blue suit I wore

my first Communion.

Always his desperate need

to be bad.

He shimmers

not fades. “I’m hungry.”

he says, “I’m you

but I’m dead.

Tell another story

about me.”

And then

the little dance,

head down,

shoulders swaying,

spinning a slow wheel

into my past.

He’s moving now

and I’ll be up

all night. He’s got

the stolen matchbook,

and the wad of cash

my mother was saving

for the family bus-trip

to my sister’s wedding–

we all end up

in separate cars.

He wants to know

if it’ll burn and when.

He’s off and kicking

the dim boy

down the block,

calling him “dickhead.”

He’s six and makes

the boy eat dirt.

Now he’s looking

for a rock:

to bust a car window

on the interstate below,

just to hear

something bigger shatter;

to split the skull

of the swan,

tie the duffel bag shut

on the kittens

and sink it like Atlantis

into the creek;

to whistle

at the crying girl:

no, he doesn’t know,

hasn’t seen

whatever

she’s looking for.

And it does no good

to tell him to keep

his hands in his pockets,

sit-down, behave.

He’s not going to keep it

to himself.

He’ll dance

like a broken marionette

until I pick up the pen,

and take him out

into the traffic

for tender introductions.

It never matters.

The last thing I say

is the next little dance

I can’t leave behind.

I have to kill him

all over again.

WHY I’M NOT A PYROMANIAC ANYMORE

A twelve-year-old boy is burning

a small pool of nail polish remover

on top of his sister’s four-drawer dresser

in her bedroom where he should not be.

He lights the fire with a match-book taken

like a tooth from the mouth

of his mother’s purse, which he found

by going into her bedroom,

where he also should not have been.

His vision caught on the burning pool,

he doesn’t see the ribbon of liquid

spill over the lip of the dresser’s top

and into the open panty-and-bra drawer-

igniting the fuse of a panty-hose leg,

the slow sizzle of a purple silk camisole.

The boy, unaware, thinks he hears

someone coming, snatches-up the matches

and scurries behind the closed door.

Minutes pass, before his nose perks

like coffee down the wrong throat,

and his eyes slowly pan across the room,

from the bed, to the night stand,

to the dresser in the corner-black smoke

billowing from its open top drawer.

The boy hears the commotion downstairs,

acrid smoke now filling the house,

and knows that the bathroom sink

is too far away for a one man bucket brigade,

knows that the flames are raging too high

to be smothered by closing the drawer.

The boy knows too, that this is the last time,

and the first time of many, he will burn,

when they open the door to find him

and his sister’s underwear drawer in flames,

pants down around his ankles,

putting out the fire the only way he could.