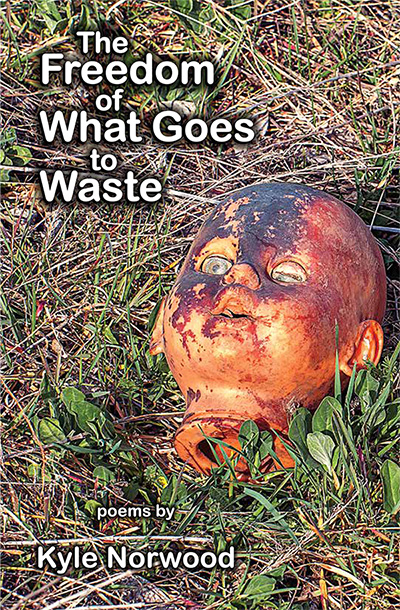

The Freedom of What Goes to Waste

poems by

Kyle Norwood

ISBN: 978-1-59948-872-1, 89 pages, $15 (+ shipping)

Release/Ship Date: May 11, 2021

The Advance Sale Discount price for this title has expired. For those who prefer to pay by check, the price is $19/book (which includes shipping + applicable sales tax) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, PO BOX 690100, Charlotte, NC 28227-7001.

PLEASE NOTE: Ordering in advance of the release date entitles the buyer to a discount. It does not mean the book will ship before the date posted above and the price only applies to copies ordered through the Main Street Rag Online Bookstore.

In a variety of poetic forms, Kyle Norwood expresses his awe and affection for the minutiae of our ephemeral lives. After earning his Ph.D. at UCLA, he taught at UCLA and at North Hollywood High School. In 2014, he was the winner of the Morton Marr Poetry Prize from Southwest Review for the poem “Landscape with Fountain and Language.” He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and son.

In a variety of poetic forms, Kyle Norwood expresses his awe and affection for the minutiae of our ephemeral lives. After earning his Ph.D. at UCLA, he taught at UCLA and at North Hollywood High School. In 2014, he was the winner of the Morton Marr Poetry Prize from Southwest Review for the poem “Landscape with Fountain and Language.” He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and son.

The appeal of the poem for me, over and above its assured lyricism, is in how each stanza describes a condition that ensuing stanzas not only deepen and elaborate on, but then reverse, transform…Norwood wisely knows that poems often say too much, say more than needs to be said. To “Let something remain unsaid,” is to allow mystery to trump the often misplaced desire to explain or be overexplicit. The envoi perfectly articulates what I’ve come to feel over the years: that we aren’t actually the ones writing our poems, and that the control we feel is an illusion. Instead, in “stillness,” we are discovered by something beyond our own will or volition: the voice that writes the poem.

~Elizabeth Spires,

judge 2014 Morton Marr Poetry Prize, The Southwest Review

commenting on his winning poem “Landscape with Fountain and Language”

Kyle Norwood’s poems embody nothing less than the struggle of insistent contraries at work in human consciousness and perception: the authentic self in tension with its projected stereotypes, the assured sense of personal will set against chance and the incalculable permutations of the universe, the immensity of feeling and vivid perception of beauty in conflict with the terrifying objective vision of its unimportance, comedy arising from its tragic core, and ultimately the fusion and clash of art and life. All of this, however, is rendered on a human scale and with precise and musical lyricism that produces the most compelling and satisfying kind of read in which a reader experiences both intimate identification and intellectual surprise. Norwood is a gifted poet.

~Stephen Taylor,

author of Cut Men and In Praise of Big Women

Riding the Swells

Out past where the waves broke, up to my neck, tensing then leaping

and subsiding, buoyed by the water, until the next great accumulation

lifted and washed me with salt: I remember riding the swells

while I held hands with a girl I liked and, feeling the force lift us, we leaped

and subsided together, facing outward and hearing the sudden crash

behind us as we sank in the trough and the little children shrieked

as their sand-castles melted, and then “Oh my God, this one’s huge!”

she said and we leaped stretching upward but still drenched

our faces, sputtering and laughing—all of this a build-up

to nothing, really, a wave too feeble to stretch

its rainbow of foam very far up the shore,

so that this rising and falling turned out to be the apex

of something that now, all disappointment washed

far into the past, seems complete in itself—the clutch and pressure

of fingers, our heightened voices, the tingle and thrust

of the swells that might very well have changed everything

for someone somewhere, farther down the beach.

Male Privilege

(1973)

My even-tempered Dad, mellowed

by his daily six pack of Brew 102,

got mad only once a decade,

so it always took me by surprise.

He was furious when he overheard

a song lyric from my favorite album,

the sound track of Hair:

“Crazy for the red, white, blue and yellow.”

For my father, “male privilege”

meant spending ten days under constant bombardment

in a trench at Okinawa,

unable to stand, unable to sleep, crouching

waist deep in a mixture

of rain water, blood, bone fragments, and spilled intestines,

all that remained of some of his buddies,

and then losing two years to an asylum,

years he could not remember,

though he was later told

that when not restrained and drugged,

he ran naked down the halls, screaming.

“Don’t try to tell me what it means.

I know what it means.

They’re calling us cowards.

They think they’re smart but they’re punks.

If they’d been in battle, they’d have wet their pants.”

*

I was eighteen, my hair was long,

I was “letting my freak flag fly.”

If that was rebellion, I was a rebel.

Each of the 365 days of the year

was assigned a draft number.

My number was fourteen.

That was a very bad number.

At my physical I was prodded and measured

by a series of doctors.

I scored poorly on an intelligence test

that measured the ability to do basic math

and identify common tools and machine parts.

My math was fine, but I didn’t know dick about machine parts,

so no motor pool for me, I’d go straight to the infantry.

I described my chronic depression

to a bored psychologist who declared me fit for duty.

Those of you with numbers under eighty should expect

to be called up in the next couple of weeks.

I was nineteen, and I didn’t know how

to make a plan.

Where to get money. How to get on a train and go.

When I tried to plan, my mind went blank.

Something was missing in me.

People said that the army would “make a man out of you.”

I was not a man. But I doubted

that the army would make me one.

*

True story: a few days later,

wandering through downtown Montrose in a daze,

I glanced at an L.A. Times vending machine

and saw the headline, Melvin Laird Ends Draft.

I have never felt more privileged

than on that day.

Faces of the Hero

Hostages, of course. And caped

cartoon avengers fight their fight

for children’s hearts, and earn their ink.

Closer to home, last Tuesday night

a team of taggers made their mark

on a broad slab of freeway pillar:

“CFK,” Crew Forever Known.

One of them, turning, saw his killer

jot down the number of their car.

Who threatened whom is in dispute.

The victor, soon released uncharged,

accepts the casual salute

of laudatory telegrams

and flattering talk-radio chat.

By the tagged pillar is a wreath

of sidewalk candles, melted flat.

This happened one mile from my house.

How honored I, a writer, feel

that heroes still require the word

to spread their fame and make them real:

oh, Joseph Campbell, in my mind

they meet again and risk their all,

where a gust blows the Daily News

against a ravished alley wall.

Luck

He was a veteran: one ear

entirely gone

and half of one nostril;

the skin over his skull

marbled and patchy, gleaming

through hair thin as a newborn’s.

We were in college together

though he was much older.

I had to look him in the eye

or not look at him at all.

It was my fault if we became

no more than “almost friends.”

He referred to his disfigurement

only once

(and I didn’t pursue the subject):

he’d recently run into

his old high-school girlfriend.

After prom night,

he would have proposed to her

except “I couldn’t get used to

the way her gums came down

too far over her upper teeth. Well,”

he said with a tight smile,

“I guess she was lucky.”

In a variety of poetic forms, Kyle Norwood expresses his awe and affection for the minutiae of our ephemeral lives. After earning his Ph.D. at UCLA, he taught at UCLA and at North Hollywood High School. In 2014, he was the winner of the Morton Marr Poetry Prize from Southwest Review for the poem “Landscape with Fountain and Language.” He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and son.

In a variety of poetic forms, Kyle Norwood expresses his awe and affection for the minutiae of our ephemeral lives. After earning his Ph.D. at UCLA, he taught at UCLA and at North Hollywood High School. In 2014, he was the winner of the Morton Marr Poetry Prize from Southwest Review for the poem “Landscape with Fountain and Language.” He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and son.