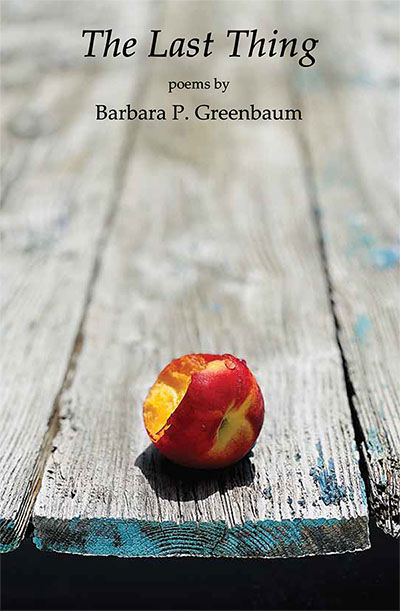

The Last Thing

poems by

Barbara P. Greenbaum

ISBN: 978-1-59948-945-2, ~48 pages, $13 (+ shipping)

Release Date: November 16, 2022

The Advance Sale Discount on this item has expired. For those who prefer to pay by check, the price is $17/book (which includes shipping) and should be sent to: Main Street Rag, PO BOX 690100, Charlotte, NC 28227-7001.

Barbara P. Greenbaum has an MFA from the University of Southern Maine, Stonecoast. She taught creative writing at Arts at the Capitol Theater, a public magnet high school in Willimantic, Connecticut. Her work has been published in Arcturus, Clementine Unbound, The Lascaux Review, The Louisville Review, The Main Street Rag, and The Massachusetts Review, among many others. She often uses the pen name B. P. Greenbaum. A long time New Englander, she and her husband now live in Winston-Salem, NC.

Barbara Greenbaum is Everywoman, artful weaver of everyday stories that invite the reader to recognize our silent voices as we walk through the woods, as we interact with strangers, as we remember those we have lost. In what may be her most compelling piece, “Dancing with Daddy”, Barbara provides a lingering reminder of all that life has to offer – security, love, joy, and sadness. The beautiful, slow video continues to play long after reading. ~Steve R. Veilleux, author of Event Horizon

Barbara Greenbaum’s The Last Thing offers the reader a seat at the head of her finely-crafted table where she serves up a feast of memories. Savor these rich courses that are well-seasoned with life lessons of longing, of grief, and ultimately of hope. Greenbaum’s collection of poetry is so deliciously universal it will satisfy long after the last syllable is digested. ~ Victoria Nordlund

The Last Thing opens with two poems that declare the roles of fate and chance in living a life. Greenbaum then weaves moments and events into a surprising, intergenerational tapestry, specific in detail, closely observed and finely felt. It is impossible to read these poems without appreciating the connections the poet makes—intimate and far-reaching and heedless of Time’s chronology. Hers, a poetic feat rich and resonant with the vagaries of human possibility. ~Pit Pinegar

GUIDING LIGHT

My mother turns on her soap opera while I,

ten years old, snuggle deep in the red recliner

and watch my mom.

Her face smiles, sometimes giggles, a look

as if she’s surprised, lips slightly parting,

then, she’s fallen in love, a bit,

a frown, a downturn of phrase, a vocal tone.

She’s living it—there—beneath

where a truth can dwell, the swollen heart,

a knocking knee rounding the bend

of someone else’s story.

Every day at three we watch

handsome people conduct perfect conversations,

share imperfect secrets,

rustle their way through love, elation and loss.

Papa Bauer, oh how we miss you. Bert and Bill,

Mike and Ed, oh that wicked Roger. Oh, Riva!

Hope Bauer, weren’t you just a baby three months ago?

What a beautiful dress, she’d say and

he’s such a hunk, don’t you think?

And I there riveting on a twitch

in my mother’s blue eye,

a curve of lip, fingers to mouth,

telegraphs through our cells.

Tonight, I am there again watching a new story,

fingernails bitten, irises aligned with hers

all those years ago, and she is here

unmistakable, raising the edge of my brow,

tilting my spotted hand.

JUST LIKE THAT

It was dark when we moved to the farm.

My father drove the GMC pickup

pulling the two horse Rice trailer filled with boxes,

hay bales, my mother’s kitchen chairs,

and a black angus steer, a year old,

who never had a name.

As headlights lit the flat gravel drive,

my brother dropped the tail gate. Just like that

the steer slipped under the back chain

and walked out into the humid, mosquitoed air.

The night moonless, the steer black as pitch,

he looked at us, as if we were the stupid ones,

and ambled toward the black.

“Cut him off,” my dad shouted.

We all moved with outstretched arms,

but the steer bolted through our thin line

to become a shrinking speck in our vision,

a ghost across the field.

My father’s curses followed. My mother said

“Calm down, remember your heart,”

as if we could forget.

Weeks and sightings followed.

Mrs. Cheeseman brought us rhubarb pie.

George saw him yesterday on the far road,

as if we knew where that was.

At school, they snickered. Oh, you’re the ones,

the FFA girls said with their intimate bovine

understandings.

My father hired the cowboys.

They came with beaten leather chaps,

tan lined foreheads, bent elbows

and wrecked knees, listened to the story,

kept an eye out. So, when the steer

showed up in Licadello’s field,

a cowhand named Heath bulldogged him

from the back of a pickup.

The steer had grown bigger,

but too thin, feral, and angry to use.

My father gave him to the man

who caught him.

Find the steer, catch him and bring him home.

It was the first thing I remember that my father

couldn’t do, until four years later

when he couldn’t stay alive.

Just like that

as I watched my father die,

my childhood slipped its chain,

gave the place one last look

and trotted off into the darkness

beyond the tree lined borders

of our farm,

to become a ghost,

a shadow crossing a field.

DONE

Today

set up the tables

borrow a dress from Cindy

talk to the florist

pick out the serving bowls

find that pair of pearl earrings

call EJ, leave another message

tell him he has to come

call Whole Foods, order platters

one gluten free, one vegan – yuck

buy liquor

call the priest

pick out a hymn

find her rings

box things from the dresser

don’t look at them

lose the grocery list three times

buy the wrong size stockings

get too many oranges

too little coffee

lose the car keys

find the car keys

yell at the dog

hang up on EJ

make two martinis

drink them both,

slowly

list all your regrets

and some of hers

Tomorrow

get up

get out of bed

wash your face

blow dry your hair

put one foot down and then

the other

bury your mother

try to forget

everything else