poems by

Anthony S. Abbott

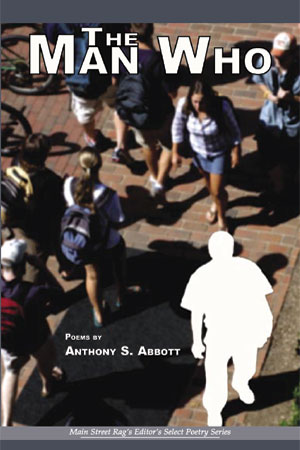

Poetry book, 84 pages, $12 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-005-3

$12.00

In stock

poems by

Poetry book, 84 pages, $12 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-005-3

ANTHONY S. ABBOTT was born in San Francisco and educated at the Fay School, Southborough, Mass., and at the Kent School in Connecticut. He received his A.B. from Princeton University, Magna cum laude, in 1957. With the support of a Danforth Fellowship he received his A.M. from Harvard University in 1960 and his Ph.D. in 1962.

ANTHONY S. ABBOTT was born in San Francisco and educated at the Fay School, Southborough, Mass., and at the Kent School in Connecticut. He received his A.B. from Princeton University, Magna cum laude, in 1957. With the support of a Danforth Fellowship he received his A.M. from Harvard University in 1960 and his Ph.D. in 1962.

From 1961 to 1964 he was Instructor in English at Bates College. In 1964 he became Assistant Professor of English at Davidson College in North Carolina. He was promoted to Associate Professor in 1967 and Full Professor in 1979. In 1990 he was named Charles A. Dana Professor of English. He served as Chair of the Department from 1989 to 1996. He was honored for his teaching with the Thomas Jefferson Award in 1969 and the Hunter-Hamilton Love of Teaching Award in 1997.

His major fields of interest are modern drama, creative writing, and literature and religion. He has directed eight plays for the Davidson Community Players, including Inherit the Wind, The Miracle Worker and A Man for All Seasons. He is the author of two critical studies, Shaw and Christianity (1965) and The Vital Lie: Reality and Illusion in Modern Drama (1989). His poems have appeared in numerous magazines and journals including New England Review, Southern Poetry Review, St. Andrews Review, Pembroke, Tar River Poetry, Theology Today, and Anglican Theological Review. His first book of poems, The Girl in the Yellow Raincoat, was published by St. Andrews Press in 1989 and was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. His second poetry collection, A Small Thing Like A Breath, was published by St. Andrews Press in 1993, and his third, The Search for Wonder in the Cradle of the World in 2000. In 2003 his first novel, Leaving Maggie Hope, won the Novello Award and was published by Novello Festival Press. The novel won the “Gold Award” from ForeWord Magazine in the literary fiction category.

With Professor Daniel Rhodes of the Department of Religion he developed a course in “American Literature and Religious Thought,” and after Dr. Rhodes’ retirement, he developed his own course, “Three Contemporary American Prophets: Flannery O’Connor, Frederick Buechner, and Walker Percy.” He has lectured widely on these three authors to both church and secular groups in North and South Carolina.

He is past president of the Charlotte Writers Club and the North Carolina Writers Network and also past Chairman of the North Carolina Writers Conference. He has won the Thomas H. McDill Award of the North Carolina Poetry Society three times. In 1978 he was a William Atherton Scholar at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference. Between 1985 and 1992 he served on the Governor’s Committee on the North Carolina Awards. In 1996 he was honored by St. Andrews College with the Sam Ragan Award for his writing and his service to the literary community of North Carolina.

He is married to the former Susan Dudley of South Orange, NJ. They have three sons, David, Stephen, and Andrew, and seven grandchildren, James, Robert, Clara, Elliot, Henry, Josephine and John.

In the Tony Abbott of The Man Who we have a master puppeteer who works them all. And when you stare into the puppets long enough (as in the Japanese Bunraku puppet theatre) the puppeteer has suddenly disappeared. Each “Man Who” is alive, just so. The range is amazing. Can you imagine the combined insights, the perceptions—at once painful and tender—of a John Berryman and a William Stafford? Look no further, Friend. Yes, “…Light creeps in/ after darkness even when we think/ it never can.”

Ron Bayes

Founding Editor

St. Andrews College Press

Tony Abbot’s The Man Who is a shape-shifter of a book, leading us subtly, often slyly, to the edge of sight and then saying, “Look!” We discover that we have been tricked into seeing ourselves, by knowing ourselves seen, much as in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo”: …”there is no place/that does not see you. You must change your life.” Or, as Abbott himself says in “The Man Surprised into Sight,” his character having come to the museum because “he’s been told to go, and he’s getting old,” one is jolted awake by what one sees: “The man’s whole life has come/to this moment, these rooms.” And upon leaving, he can see his breath. When poetry has enabled us to see our own breath, it has fulfulled its promise. It has helped give us walk back into our lives.

Kathryn Stripling Byer

North Carolina Poet Laureate

“The man who” speaks these poems is not one person but many. He is his own circle of friends, his own significant landscape, his own company and his private solitude. With engaging modesty and lovely candor Anthony Abbott has written of, and from, the myriad different ways of perceiving that time and circumstance produced in each of us. Here the Latin motto—from many one—is both true and reversible. From the many that are one come these quiet, disquieting revelations. Here is the true and the genuine.

Fred Chappell

former North Carolina Poet Laureate

THE MAN WHO LOVED ANIMALS

July Fourth, early evening, family

and friends gathered, sun setting, fireworks

an hour away, the dog not in his

accustomed place beneath their feet. They find

him in the woods, half buried, surely gone

to die.

Surprisingly the doctor’s office answers.

A young vet sewing up a cat says, “Bring

him in,” and all of them carry the dying

dog to the waiting van. The doctor

operates at once, and the dog lives

for five more years.

Now, another July morning, Southern sky

hazy blue, the doctor drives to work, son

and heir in his infant chair, facing backwards

as the law prescribes. In his mind he drops

the baby at the sitter, then drives to work,

his brain churning with the day’s events:

surgery on an old dog’s eye, an evening

meeting at the Y.

The car bakes all day in the summer sun.

At five he leaves to retrieve his son.

The boy, he’s sure, has played all day,

napped and sucked the bottle willingly

from the woman’s careful hands. He finds

the child silent as a doll.

Over and over his broken heart replays

the morning’s ride. He knows he dropped the baby off.

So what can we say

Of this man who loves the red ears of foxes,

the padded paws of long-legged dogs,

and the soft fingers of his infant son?

That God loved him, loves him still, even after

he has lost all hope of love–that light creeps in

after darkness even when we think

it never can. I know nothing about walking

into light, not even how to take the first step.

But the god who numbers the small bones

in the sparrow’s wing can take the fingers

and the light and shape them into something

new.

This I know and he, I think, knows too.

THE MAN WHO STUDIES ITALIAN

listens to his language tape

as he drives to work. “Buongiorno,”

the pleasant lady says. “Buongiorno,”

he responds. He learns “grazie”

and “bona sera” and the ever useful

“prego.” But by Exit Twenty-Five

when the snarl begins, these words

do not suffice. “Proca miseria!”

he shouts at the purple Chrysler

Cruiser that cuts him off. “Stronzo!”

he yells when the traffic stops—

“Stronzo! Stronzo! Stronzo!” as he thumps

padded wheel, a curious mantra.

By Exit Twenty-Eight his voice

is hoarse from chanting “pezzo di merda”

like a Verdi aria. The hard hats

in the construction site wave.

He watches the faces in other cars.

Honda, Lexus, Saturn, Mars.

No one there beating his head

rhythmically against the briny windshield.

“Figlia d’un culo” he whispers.

The radio the other day had spoken

of a man who stripped off all his clothes

in the middle of Independence Boulevard

during the morning rush hour. No wonder.

“Vanfanculo!” he cries rolling his window

down to make the universal sign. “Vanfanculo!”

he cries again, as the language tape rolls on.

THE MAN WHO SPEAKS TO HIS DAUGHTER

ON HER 40TH BIRTHDAY

May 8, 2003

1.

“Poetry is the supreme fiction,” says Wallace Stevens.

I know. Then how to express the truth, simple

and unadorned as Stevens’s “dresser of deal.”

You see, I am already equivocating, ducking

behind the decoration of language. So, stop me.

Good. That’s better. Now, tell me where you are.

If that’s too hard, just tell me—something.

Or appear to me in a dream, or leave a symbol somewhere—

some mysterious talisman that lets me know it’s you.

Not the feather floating down trick, that’s too common.

Nor bumping around in the old house. Something original

like your name spelled in shells before the tide comes in.

2.

All right, let me try it another way. When you were

three, I let you go to school in the winter without

leggings, without anything to warm your legs.

The teacher told me at the end of the day

and I burned with shame. You were my favorite person;

I was yours. And what I really want to know—

now that all the nonsense about your ghostly reappearance

is out of the way—what I really want to know is

where we would have gone, you and I. I want

to think of you at fourteen or twenty-four

or even thirty-one, want to picture you, know

the clothes you would have worn and how

you would have cut your hair. Early this morning

I walked in the rain to your grave. The tree is gone.

You know I picked the spot because the tree

was there, and now it’s vanished like my images

of you. Damn it, anyway. I’m supposed to be

a writer, supposed to create you at twenty-five

or thirty-nine, give you a history. What would

you like? A husband, three children of your own?

A law practice in the suburbs of Boston?

3.

I’m such a romantic fool. That’s the problem.

The way I see it, I’m sitting in a tea room

in London, it’s raining, of course it’s raining.

Umbrella stand inside the door. Dripping coats

hanging on the wall. My hands cupped around

a hot mug of tea. I’m breathing steam. I look up.

There you are, at forty, looking at me with so

much love I feel my body rising from the floor.

You walk over. I try to stand. “No,” you say,

“Sit down and rest.” You place your hands

on my head and tell me all the years were

nothing—a grain of sand , one grain of sand—

that’s all. You tell me you’ll come for me

whenever it’s right, and then you’re gone.

The bell rings, door closes, flash of a heel

And then, nothing but the steady fall of rain.

They look at me, there in the shop, all of them,

and then I laugh and cry, too, I’m sure.

Pretty improbable, don’t you think? Wouldn’t

sell even in Hollywood, or would it? Still,

dammit, I wish you’d talk to me.