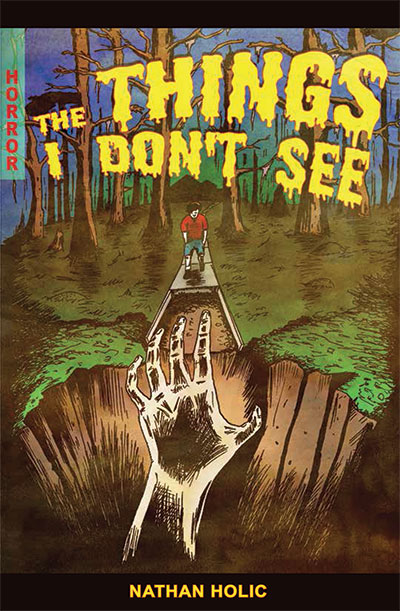

A Novella by

Nathan Holic

ISBN: 978-1-59948-506-5, ~120 pages, $12 cover price

Release date: February 10, 2015

Synopsis

Craig, a struggling cable service tech, lands a deal on a brand-new house in an under-construction Orlando neighborhood. It’s supposed to be his family’s ticket to the elusive middle class, the cure for an embittered marriage, the thing that maybe even helps his strange step-son Taylor to finally accept him as a father.

But there are a lot of things that Craig can’t see.

Taylor, for starters, is troubled. He’s involved in unusual incidents, drawing images where all the homes in the neighborhood are burning and sneaking off to someplace, deep within the woods. Something’s wrong with the neighborhood, too. It’s Central Florida in 2009, the housing market is collapsing, the construction equipment is gone. Will the neighborhood that seemed like such a dream ever become anything more than just unfinished roads and empty plots in the middle of nowhere?

The Things I Don’t See is the story of a fractured family on the fringes of America’s happiest vacation destination. It is the story of what takes place outside the comic panels and cartoon frames and family photos, and what it means when we finally encounter the truth behind our lies.

Nathan Holic teaches writing courses at the University of Central Florida and serves as the Graphic Narrative Editor at The Florida Review. He is the author of the novel American Fraternity Man (Beating Windward Press), and the editor of the anthology 15 Views of Orlando (Burrow Press), a literary portrait of the city featuring short fiction from fifteen Orlando authors. His fiction has appeared in print at Iron Horse and The Apalachee Review, and online at Hobart and Monkeybicycle. His comics and graphic narratives have been published in Palooka, Atticus Review, and Sweet, and his serialized graphic novel (Clutter, told in the form of a home décor catalogue) is available online at Nailed Magazine.

Nathan Holic teaches writing courses at the University of Central Florida and serves as the Graphic Narrative Editor at The Florida Review. He is the author of the novel American Fraternity Man (Beating Windward Press), and the editor of the anthology 15 Views of Orlando (Burrow Press), a literary portrait of the city featuring short fiction from fifteen Orlando authors. His fiction has appeared in print at Iron Horse and The Apalachee Review, and online at Hobart and Monkeybicycle. His comics and graphic narratives have been published in Palooka, Atticus Review, and Sweet, and his serialized graphic novel (Clutter, told in the form of a home décor catalogue) is available online at Nailed Magazine.

In The Things I Don’t See, Nathan Holic gives us a man and his world so fully and with such honesty that we align ourselves with him, his every hope and terror. This hard-working everyman endures the avalanche of small devastations that roll into large-scale disappointment, and he is achingly sensitive to the awful implications of the things he does see. In this thoroughly absorbing and often harrowing tale, Holic masterfully leads us into the heart of the dark underbrush of male experience and family life in the working class south.

–Susan Lilley

i.

I came home from work on a cold January evening to find my step-son Taylor on the front porch in a t-shirt and shorts, drawing in his sketchpad while the rest of Central Florida was taking refuge in the heat of their living rooms. Though the sun had never really risen that day, we were now long past sunset, and there’d been a freeze warning every night that week; driving around town, it seemed as if everyone was wrapping blankets around their front-yard tropical plants, Christmas lights around the trunks of their avocado and citrus trees to keep them just warm enough that they wouldn’t die. But here was Taylor: ignoring the goosebumps and blue-white skin, disobeying the laws of nature as if they were no more than house rules I’d set up to annoy him.

And here was the most troubling part: for him, this sort of weird behavior had become normal.

I made a shiver motion, hugging myself; I exhaled sharply so Taylor could see my breath. “Boy, you love creating, don’t you?” I asked. Against my better judgment, and to save this unraveling family that I’d stitched together six years before, I was following my wife’s instructions to encourage without qualification. Didn’t matter if I found him constructing Blair Witch-style stick men and hanging them from trees in our backyard, or if I found him slicing slits in old t-shirts, soaking them in coffee, calling it all a “fashion experiment”…no matter the strange shit he was up to, I was supposed to say “Good job!” or “Cool!” or whatever else you say to an 11-year-old who isn’t yours and will never be yours but for whom you’ve dedicated yourself—from day one of the marriage—to be a dad, a real dad. Of course, I always thought that “real dad” was supposed to mean the good and the bad, the encouragement and the discipline, but things got complicated somewhere along the way.

“What do you mean?” Taylor asked. His cheeks were red, and I wasn’t sure how he was able to hold his pencil without his hands shaking. But he didn’t act like he was cold.

“Your artwork. Nothing stops you.” I pulled my jacket tighter. “Not even the weather.”

“Whatever,” he said.

“No, I’m not giving you a hard time. I think it’s great,” I said, thinking: encouragement. “What are you drawing now? Landscapes?”

“A dungeon.”

“A dungeon?”

“For the undead,” he said. “The ones we want to keep.”

I lost my footing. I’d been trying to stand casually with one hand pressed against the doorframe for balance, but now I stumbled and knocked into the door. “Taylor,” I said. “Come on.” The neighborhood seemed darker that night, and I finally noticed that two of the streetlights had burnt out. Several others—farther down the street, down where the subdivision was unfinished and unpopulated, dirt and two-by-fours and discarded Burger King bags and loneliness—flickered like bug zappers.

“It’s started, you know.”

“Taylor,” I said again.

“The neighborhood is dead.”

“It’s not dead, Taylor.”

“Look around you.”

“Please come inside. It’s too cold out here. Your mother is going to worry.”

And I knew in that moment that we were close to the end, me and him, me and my wife, but still I hoped that I could salvage our little flawed family, change the role I’d accepted for myself long before; still I hoped—even though the sky was cracked gray and the acres of cypress trees surrounding the neighborhood seemed not just to have gone winter-dormant, but to have died in some terrible post-apocalyptic way—still I hoped I could make the right choices, say the right words, so that I wouldn’t lose them in the same way I’d been lost.

Nathan Holic teaches writing courses at the University of Central Florida and serves as the Graphic Narrative Editor at The Florida Review. He is the author of the novel American Fraternity Man (Beating Windward Press), and the editor of the anthology 15 Views of Orlando (Burrow Press), a literary portrait of the city featuring short fiction from fifteen Orlando authors. His fiction has appeared in print at Iron Horse and The Apalachee Review, and online at Hobart and Monkeybicycle. His comics and graphic narratives have been published in Palooka, Atticus Review, and Sweet, and his serialized graphic novel (Clutter, told in the form of a home décor catalogue) is available online at Nailed Magazine.

Nathan Holic teaches writing courses at the University of Central Florida and serves as the Graphic Narrative Editor at The Florida Review. He is the author of the novel American Fraternity Man (Beating Windward Press), and the editor of the anthology 15 Views of Orlando (Burrow Press), a literary portrait of the city featuring short fiction from fifteen Orlando authors. His fiction has appeared in print at Iron Horse and The Apalachee Review, and online at Hobart and Monkeybicycle. His comics and graphic narratives have been published in Palooka, Atticus Review, and Sweet, and his serialized graphic novel (Clutter, told in the form of a home décor catalogue) is available online at Nailed Magazine.