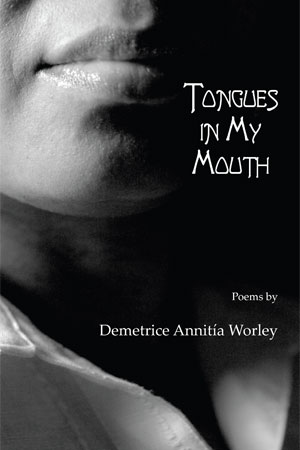

poems by

Demetrice Anntía Worley

Poetry book, 90 pages, $14 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-283-5

$14.00

Available on backorder

poems by

Poetry book, 90 pages, $14 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-283-5

Demetrice Anntía Worley‘s poetry appears in journals including Reverie, Permafrost, Spoon River Poetry Review, and CLR and in anthologies including Forty-Four on 44; Women.Period.; Risk, Courage, and Women; Temba Tupu! (Walking Naked); Bread and Steel (Audio CD); and Spirit & Flame. Also, she is co-editor of Language and Image in Reading-Writing Classroom: Teaching Vision and African-American Literature: An Anthology, 2nd edition. Her honors include selection as a Cave Canem Foundation Fellow; runner up, Knee-Jerk‘s 2010 AWP Bookfair Buddy Story Award; third place, 2009 Split This Rock Poetry Contest; semi-finalist, 2009 Many Mountains Moving Press Poetry Book Prize, semi-finalist, 2009 and 2006 Crab Orchard Series in Poetry First Book Award; finalist, 2007 Allied Arts Center Midwestern Voices Artist Residency/Fellowship; and finalist, 2002 Editor’s Prize Spoon River Poetry Review. She holds a D.A. from Illinois State University, and teaches writing and literature at Bradley University. Daily, she visualizes world peace.

Demetrice Anntía Worley‘s poetry appears in journals including Reverie, Permafrost, Spoon River Poetry Review, and CLR and in anthologies including Forty-Four on 44; Women.Period.; Risk, Courage, and Women; Temba Tupu! (Walking Naked); Bread and Steel (Audio CD); and Spirit & Flame. Also, she is co-editor of Language and Image in Reading-Writing Classroom: Teaching Vision and African-American Literature: An Anthology, 2nd edition. Her honors include selection as a Cave Canem Foundation Fellow; runner up, Knee-Jerk‘s 2010 AWP Bookfair Buddy Story Award; third place, 2009 Split This Rock Poetry Contest; semi-finalist, 2009 Many Mountains Moving Press Poetry Book Prize, semi-finalist, 2009 and 2006 Crab Orchard Series in Poetry First Book Award; finalist, 2007 Allied Arts Center Midwestern Voices Artist Residency/Fellowship; and finalist, 2002 Editor’s Prize Spoon River Poetry Review. She holds a D.A. from Illinois State University, and teaches writing and literature at Bradley University. Daily, she visualizes world peace.

What an opus Demetrice Anntía Worley has created with Tongues in My Mouth. The stark and beautiful truths she explores are ones we ought to know and begin to view. This book needs to be on every desk. Thank you Demetrice Anntía Worley, for your insight. For your bravery. For your soul stirring. Tongues in My Mouth is an important book.

–Nikki Giovanni

This heartfelt and necessary book, full of wisdom and womanly logic, arrives as a divine gift to us, a fully mature collection woven into beauty by the astute hands of its maker. Demetrice Anntía Worley brings us soothsayer truths wrapped in sensuous rhythms–edgy humane poems that never cease to confront and console. I am so happy to hear this poet’s varied and various tongues, to be able to savor her multitudinous and generous voice. Long may it–and this book–prosper!

–Allison Joseph

Demetrice Anntía Worley’s harrowing and ultimately redemptive book traces one woman’s emergence from isolation to social engagement. Fraught with violence both verbal and physical, this is a survivor’s tale, revealing the ways we humans remain prisoners of our own silence and (mis)assumptions. Only when we risk the words to speak our lives into being, she edgily persuades us, may we merge with our worldly sisters and brothers. Eidetic and electric, this poet’s vision forges unity from panoply of colors and of ancestors. It’s these — the poet’s silenced forebears and contemporaries — whose tongues find compelling voice in hers.

–Kevin Stein

FOREWORD

A Critical Voice: A Forward

Forewords for poetry collections can sometimes get in the way of the pleasures of discovery that often come from simply engaging a collection without the inevitable filter of a foreword. Of course, many who know this and are concerned about this, skip the foreword, and so I am clearly writing this for those of you who don’t. Those like myself, who read forewords, should at least be assured that what I am attempting here is neither an academic appraisal of Demetrice Anntía Worley’s elegant first collection of poems, Tongues in My Mouth, nor is it an attempt to direct the reader on how he or she should encounter the work. I welcomed the chance to do this foreword because I have, in my cultural archive, a definition of the word “forward” that has less to do with the staid confines of Western academia and publishing, but with the dancehall of reggae culture. In the 1980s and 90s, a “forward” constituted a public expression of encouragement, affirmation, and a command to the artist to do what he or she does because by doing so the artist is advancing the cause of art, the cause of the dance, the cause of the struggle. So a crowd would shout, “Forward!” to an especially adept deejay or singer and that would be the greatest compliment ever. The word would become a noun, as in “yeah man, a nuff forward me get a de show,” etc. So, what I do here is to champion Worley, celebrating the work she has managed to produce and offer her “nuff forwards” for this really important work. At the very least, you will know something of why I admire this work and why I am willing to stand in the crowd and shout, “Forward!”

Demetrice Anntía Worley’s strengths as a poet are found in unexpected places for even as she is clearly a poet of witness, a poet committed to the task of truth-telling and political daring, it is in her craft, her impeccable poetic timing and her delicate management of sentiment and emotion that we witness her affecting powers as a poet. She is a meticulous craftsperson and she surprises us with the sharply drawn insights into human nature, even as she allows herself to admit to bewilderment at the inconstancy of human beings, including herself.

The poems in this book are united by a fascination with language-not for its linguistic possibilities alone, but for the very act of speaking, the very act of using words to fill empty spaces with meaning and confusion. In this sense, Worley’s first book is about saying those things she has been longing to say for years. One has the sense that even as she seems intent on communicating with us with an audience, she is equally intent on, and satisfied with the empowerment inherent in the act of simply speaking to herself. Thus her poems are confessional in the strictest sense of that term. They confess, not to a confessor who will offer absolution, but they are confessions to the self, confessions that become public without leaving the viewer with the feeling of being a voyeur. She is not spilling her blood on the page-there is very little that could be deemed indulgent in these poems. Instead, she is using the poem to discover the truth inside of experience. She takes risks. Her greatest risk lies in her ability to say that she cannot confidently say that she understands everything she has seen, done, or heard, but to not let this silence her. Indeed, she is also saying that by writing these poems she may find her way to some meaning, even if the meaning lies only in that remarkable alchemy that poetry can be-that process of turning the mundane, the profane, the abject into something sublime, without ever diminishing the core of that thing. The metaphor is probably not correct. She is not changing anything, but discovering that which is inherent in the things she is seeing. When the blood from a woman’s head, after she has been hit by her lover, is described as a beautiful flower blooming on a white tile, you know that beauty is not pretty, is not quaint, is not a deception-it is merely the inner value of a thing, even an ugly thing, that is shining through.

My love,

a red rose,

blooms

on the white tiled floor.

Violence, too, can be retrieved and managed by the act of retelling. Her blood on the white tile is like a blooming rose. Thus the violence becomes more alarming. The echo of Burns is not accidental, of course, but the startling violence is more pronounced by the juxtaposition of Robert Burns’ not entirely un-melancholic lyric, “A Red, Red Rose”. Worley’s allusions to classical texts abound in the work, but she never does this to show off-indeed it is delicate handling of such moves that makes her work achieve the kind of layering that rewards constant rereading. In “Morning Clothes” she puns somewhat obviously in the title and then invokes Shakespeare’s Macbeth in the phrase “tomorrow’s tomorrow”:

Tomorrow’s tomorrow will find

me in mourning clothes, white

as our love, full as our hearts,

when we last talked, making plans

for lunch, coffee at the café,

to right the world.

There is a delicate turning of suffering into beauty-it is the alchemy that makes the blues possible, or a song of lament into something close to sublime joy. But it is her mastery of craft that allows her to manage such fine tuned moves. It is how she turns the black of mourning clothes into something white; and the way she makes us ache when we think that she is talking about the loss of a friend who shared with her the fantasy of righting the world. Suddenly, her helplessness and the “un-rightness” of death weigh heavily on us. And yet, there is no other way to describe this deft management of grief but as something beautiful.

Worley is a poet of witness. She writes like one who has spent time obsessing about the ideas that have caused her concern and pain, and she has finally had the chance to shape those thoughts and obsessions into music. Her poems are engaged in the way that citizen poets engage with the social and political realities surrounding them. But it is hard to find an agenda here other than the compelling art of truth telling. And this is why her poems can shift with complete ease from the consideration of the fate of Asata Shakur, a political prisoner in the American system, to her mother’s callous disregard for the suicide of her own daughter. What makes these subjects part of the same impulse for Worley is the fact that they dare to expose the shock or inhumanity in those whose callous disregard for the suffering cause them to speak painful things about the victim. Her dead sister has no voice, and Worley dares to upend the notion of a mother’s pure sentiment for her offspring-and she does this with the same commitment as she does the notion of a politically just system in American society. Someone is lying, and she won’t allow the lie to stand.

In “Promises”, and in the poems from the section, “Outline” we see the delineation of the hurts that shape a woman’s identity. In “Promises” hurt is an understatement-a white doctor who molests a girl and a man who comes by her home and does the same. There are no answers, no way to process into rage the confusion of a five year old. All she can do is run. It is Worley’s skill that allows the subtlest of cracks that becomes a chasm of pain: “I closed my eyes. It hurt to be me.” One has the sense that this is both the voice of the girl and perhaps even more, the voice of the woman who was the girl.

Worley finds poems in the luminal moments of life-places where things change. Her poem, “Judgment of Dissolution-A Found Poem”, about divorce, for instance, takes the dry legal language and manages to create a subtext that is filled with the pain and disappointment of divorce. Somehow, the lack of children in the marriage is a metaphor for a great deal that has been sterile/barren in the marriage. In italics, the commentary is stark:

One spring I dreamt babies,

playing on my lap, tugging

at my hair, sleeping in my arms.

He was not ready.

Four years later he pleaded,

I refused to respond.

The subtitle, “A Found Poem” is almost a misnomer for Worley since there is a real sense in which all her poems are “found poems”. She salvages these beautifully formed pieces from the details of her live and her encounters with the world whether she is meditating on the idea of being alone, the shadow of divorce and separation palpable in the space she occupies in the poem “Building Fires”, or her time reflecting on the meaning of invisibility and femininity in her poems set in Cairo (“An African American Woman’s Offering: A Bop”). And even when she is being unabashedly political and protesting at full throttle, she remains fully whole, fully present emotionally. Note, in the harrowing poem “America Declares War on Girls”, the way the moan of the poet as she watches the news and finds herself transported to the scenes of so many brutish crimes against girls, becomes the moan of the girl at the end of the poem–a moan that is eventually silenced:

He pulls her white cotton panties

below her knees, jabs a stick into her vagina.

She moans. He stuffs yellow/brown leaves

in her mouth, stops her voice, her cries, her breath.

This silencing, this press towards voiceless-ness is at the heart of these poems. And so we gradually come to recognize the sophistication of her sectional–titles (“Articulate”, “Vocalize”, “Outline”, and “Testify”) and, more importantly, of her collection’s title, Tongues in My Mouth, where the entire book becomes a contemplation on the meaning of voice-the meaning of saying on so many levels. Here, it is the woman’s voice that seeks to say what must be said, and importantly, Worley recognizes that there are many voices richly gathered in her mouth. The poems push back against the tyranny of silence.

It is common practice now to try to underplay any suggestion that the “I” in a poem is even remotely related to the poet. We speak of the “speaker” and the “persona”, working hard to create a distance between the poet and the voice in the poem. Of course, it is an act of presumptive politeness on our part, an act that seeks to not presume too much of the poet, and that seems to want to allow the poet the freedom to be as inventive as possible without the tyranny of assumptions about autobiography. The downside to this, of course, is that it shares much with some deconstructionists who would argue the death of the author. An absurd idea for poetry, but one that still holds sway in some quarters. I fear, though, that we often, in the process, lose sight of the sheer courage and risk that a poet undertakes to tackle certain subjects and to, in the process, reveal herself. While I have not attempted to align Worley’s biography with the details in her poems, I venture to say that she is of the view that all poetry that we write is, at some level, autobiographical in all the ways that autobiography, though slippery and unreliable, is ultimately personal.

I leave this collection feeling as if I have been in the presence of a woman called Demetrice Anntía Worley, a poet who has learned to take the detritus of life and turn them into powerful and moving statements about self and about community. She has seen hard things, she has lost loves, she has flirted with the outrageous and the taboo, and she has come out of all of this with the grace that comes from making wonderful art. If, like me, you are as much drawn to the narrative of our daily lives with their mundane happenings and dramas alike, as you are to the brilliance of well-developed craft and the practice of elegant verse writing, then you will find much to enjoy in this collection of poems that do not shy away from tough political questions and troubling emotional and psychological issues.

For you to echo my “forward” of affirmation and praise for this collection, you will have to read these poems, and come to your own conclusions about their power and force. My expectation is that you will join me in shouting “forward!” when you are through.

Kwame Dawes

Columbia, SC

Samples

Coming to Know Things

i.

Michelle, at fourteen you knew things

I couldn’t understand, like FM radio

waves rolling across your new stereo,

a fuller sound than my tinny AM transistor.

Nearly every FM station sounded like

nasal tones, “Public Radio,” except

the ones playing hard guitar twangs

I’d never heard on Chicago’s WVON,

“Voice of the Negro.”

ii.

Michelle, at fourteen we listened to songs

pressed into black vinyl, LP albums you bought

for the amazing price of eleven cents, a penny

per platter. White bands I didn’t know like

Clear Water Revival, Steely Dan, and

Bachman Turner Overdrive made you dance

across your stepmother’s glossy hardwood floors.

When you read the record club’s

collection letter, you laughed, explained

how you didn’t use your own name

on the order slip; told me even Perry Mason

couldn’t convince a jury that a black girl

living on Chicago’s west side would listen

to Lynard Skynard. I believed you

when you said, “I didn’t commit a crime.”

iii.

Michelle, at fourteen we kissed,

said we were friends for life. I wanted

you to soothe me with kisses like those

you shared with Eric; he filled you

with more than my wonderment.

The girls called you “nasty.”

I/he/we knew milk breath sweetness,

silky sweat, black feathered line

from navel to pubes.

Tongues in My Mouth

Behold, I open my mouth;

the tongue in my mouth speaks.

— King James Bible, English Standard Edition, Job 33:2

Tired of waiting for me,

my ancestor’s spirits are lifting

my heavy tongue, forming

words in my mouth.

Tuwa wasteicillia maka kin lecela

tehan yunkelo, my paternal

great-great grandmother’s Sioux voice,

guides me beyond concern for self.

Sa koon ain je gun, my maternal

great-great grandmother’s Blackfeet voice,

the light of her soul, locates my words

Ewúro ò fi tojo korò, my foremothers’

Yoruba voices tell me, listen,

hear the wisdom.

My ancestors are making me

practice my languages,

forcing me to make foreign sounds,

to turn new words over,

until the tongues in my mouth

speak in a single voice,

until the tongues in my mouth,

speak the truth that no one wants to hear.

Colored Girl

In 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr., died

I stopped being colored.

Sitting cross-legged,

on avocado shag carpet, I stare

expressionless at our nineteen inch

black and white television-

Samantha Stevens rides her broom

side-saddle across Bewitched’s

opening credits. Newsbreak:

Walter Cronkite’s pale eyes

do not blink as he informs

the nation, Negroes are rioting,

on Chicago’s west side, in Harlem,

Watts. Across our Zenith’s screen,

light and dark gray images shift,

people running, buildings burning,

a colored man, carrying a naked

white mannequin, raises his fist,

cries, Power to the people.

I wondered about darkness as only

an eight year old child can wonder-

That April evening, standing

in my parents’ bedroom,

forehead pressed against

the cool window pane,

I watch the orange glow

from the riot’s flames, radiate

on the Chicago’s horizon

when would blackness envelop

my caramel-colored skin.

You must be logged in to post a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.