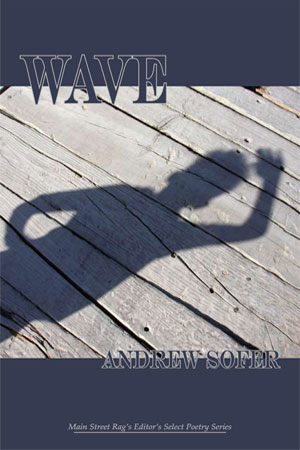

Poems by

Andrew Sofer

Poetry book, 96 pages, $14 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-262-0

Release date: 2011

$14.00

Out of stock

Poetry book, 96 pages, $14 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-262-0

Release date: 2011

Andrew Sofer grew up in Cambridge, England, and, after boarding school, studied at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Boston University, and the University of Michigan. His numerous poetry awards include Southwest Review’s Morton Marr Prize; Atlanta Review’s International Publication Award; First Prize in the Iambs & Trochees Contest; and New England Poetry Club’s Gretchen Warren Award. Wave, his first book of poems, was named a finalist for the Morse Prize, the Donald Justice Award, and the New Criterion Prize. Andrew has acted and directed widely, and his writings on theatre include the acclaimed book The Stage Life of Props. He teaches in the English department at Boston College.

Andrew Sofer grew up in Cambridge, England, and, after boarding school, studied at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Boston University, and the University of Michigan. His numerous poetry awards include Southwest Review’s Morton Marr Prize; Atlanta Review’s International Publication Award; First Prize in the Iambs & Trochees Contest; and New England Poetry Club’s Gretchen Warren Award. Wave, his first book of poems, was named a finalist for the Morse Prize, the Donald Justice Award, and the New Criterion Prize. Andrew has acted and directed widely, and his writings on theatre include the acclaimed book The Stage Life of Props. He teaches in the English department at Boston College.

Andrew Sofer is a poet of wanton heed and giddy cunning, capable of breezy rhymes and puns, but also of directness and vigor. These poems are reconnaissance missions into the private past of the speaker. Their graceful formalities refine autobiographical slag back into significant shapes of experience re-imagined, re-felt, re-found. In wit, in swift and fluent narrative, and in variations on conventional imagery, this poet makes an emotionally believable world.

–Rosanna Warren

WAVE marks a mature and accomplished debut. Sofer’s poems, like the title, are deceptive in their surface elegance and simplicity. Is this “wave” a billow of water, the motion of sound, a surge of emotion, a gesture of welcome, or leave-taking, or all of these? The unshowy mastery of technique contrasts with strong, deep undercurrents of emotion: a childhood grief rippling into adulthood, tides of parental joy in watching new life unfold. The insistent repetitions of the pantoum in the devastating “Noughts and Crosses” embody a child’s dazed inability to grasp a tragedy; while in “Wittgenstein in Norway,” the form aptly mirrors Wittgenstein’s own obsessions with language and tautology. Sofer is equally at home in a nimble free verse as in more formally patterned stanzas-both exhibit a quiet authority. Sofer’s facility with language perhaps belies a more problematic relationship with identity and culture. But poets are always outsiders, translators of their own experience. The difficulty of translation itself provides the perfect metaphor for this collection: “our last shalom / somewhere between goodbye and peace.”

–A.E. Stallings

Among the infinitely wise, infinitely tender voices speaking in these poems is that of Orpheus, who commends “the ruse / we know as equal temperament.” He is speaking, of course, about the system of musical tuning that relies upon a series of “calculated instabilities” to produce the magic we construe as harmony. WAVE is dense with the lived joys and sorrows that might easily, in lesser hands, amount to dissonance. But Andrew Sofer, in this fine and remarkably mature first book, has found their richer temper.

–Linda Gregerson

Kafka’s Farewell

Scratching out The Castle, plagued

by hemorrhoids, boils, and the TB

uncoiling in his chest like a viper,

how he envied those warm bodies

at Spindelmuhle whizzing past

his window, all schnapps and good cheer.

Did he lie at the bottom of the slope,

black limbs twitching air, target

of catcalls and apple cores?

My situation in this world

would seem to be a dreadful one,

alone here on a forsaken road.

Did he dream of hurtling

down the trail, bowler hat,

stiff collar and scarecrow ears–

then relax into the schuss

of it, snowplough to stem christie,

stem christie to parallel turn

as he swoops into the sky

shedding jacket, coat, and hat.

Look, a child cries, a flying Jew!

Walking to Moscow

My older brother sets off for Moscow

wearing thick boots and a thin scarf.

As he leaves London, sleet falls.

He reaches Harwich in a few hours

and walks over the English channel

past astonished ferries. 1990:

he writes that Germany seems full

of people standing in squares

as if listening to important speeches

or deaf. In a Munich campground

a fat man with sad eyes rests

his hand on my brother’s knee,

invites him to his tent to drink

Pilsner and listen to Schubert lieder.

My brother refuses. In December

he runs out of food

and begins to consume his past,

starting with his childhood.

My brother never arrives

in Russia. Our grandfather waits

at a crossroads in Kajanadoc

in his old peddler’s cart

whose loose wheel will soon

spin off and kill him,

raising his lantern

as it begins to snow.

Cambridge Now

Our living room and dining room are gone,

as is the Garden Room where I would play

the sick piano, bored on my half-terms,

while Mr. Sadler sweated on the lawn.

He’d tip his cap and shift his eyes away,

muttering Sir, and I would turn beet red,

knowing I was younger than his son.

I helped him pick our apples where they lay

beneath the tree, checking the worst for worms,

their musty bulk rotting the garden shed.

I find the study where my parents worked,

desks side by side, hers in a messy pile

of papers, Freud’s complete works, a small fern.

My father’s desk was neat. I often lurked

until he left and raided his velvet file

for drawing paper. It put him in a rage.

He’d shout at me until my shoulders jerked

with tears. Then he’d recover, gravely smile

and say he was sorry, but I had to learn

the hidden cost of every wasted page.

My mother’s room smelt faintly of cologne

and medicine. Surrounded by her books,

she lay in bed with all the blinds pulled down,

pretending she was talking on the phone.

She used to joke about our firing Cook

but still served Campbell’s soup day after day

then crept upstairs to have a bite alone.

In later years her chap would catch my look

at table, quickly tie his dressing-gown,

and help her clear the dirty plates away.

The owner leads me up the creaking stairs.

Perched on a step, I’d read for hours on end,

picking the worn green lino into shreds–

our family never went in for repairs.

My fingers trace the banister round its bend

past the landing to my bedroom door.

I open it expecting stained blue chairs,

the broken spacecraft built for my best friend,

my vampire collection, typewriter, bunk beds.

We put our kitchen on the second floor.

I sit down at a table of stripped pine

and force myself to look. The room is bright

with sun cascading through the window pane

and cheery with a warmth that isn’t mine.

It used to get so dark in here at night

I made my mother put a light outside

the door I had to close when I was nine.

My hand shakes, spilling tea. Are you all right?

I nod, but at the cracked sink once again

I rinse my eyes, like the day my father died.

You must be logged in to post a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.