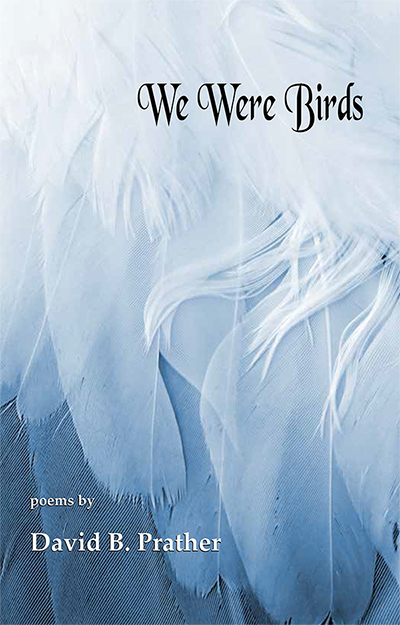

We Were Birds

poems by

David B. Prather

ISBN: 978-1-59948-773-1, 88 pages, $14 (+ shipping)

Release Date: November 19, 2019

$14.00

poems by

ISBN: 978-1-59948-773-1, 88 pages, $14 (+ shipping)

Release Date: November 19, 2019

David B. Prather earned his MFA from Warren Wilson College. He was a poetry editor for Tantra Press and Confluence, and he taught at West Virginia University—Parkersburg and at Marietta College in Marietta, OH. After studying acting at the now defunct National Shakespeare Conservatory in New York, he spent almost two decades performing and directing at the Actors Guild of Parkersburg, where he garnered several local awards. He also appeared in two independent movies: Christ Complex, and White Zombie. David also worked as a Pony Express courier, a parking lot attendant, a movie-rental cashier, an administrative assistant, and as a retail store manager.

David B. Prather earned his MFA from Warren Wilson College. He was a poetry editor for Tantra Press and Confluence, and he taught at West Virginia University—Parkersburg and at Marietta College in Marietta, OH. After studying acting at the now defunct National Shakespeare Conservatory in New York, he spent almost two decades performing and directing at the Actors Guild of Parkersburg, where he garnered several local awards. He also appeared in two independent movies: Christ Complex, and White Zombie. David also worked as a Pony Express courier, a parking lot attendant, a movie-rental cashier, an administrative assistant, and as a retail store manager.

With We Were Birds, David Prather has written not simply a collection of poems, but a deep meditation on the freedoms and constraints of life on earth. His attention to birds, to the sky that is their element, and to the plants underfoot, is acute, and always shadowed by a poignant awareness of life’s fragility. His voice is compelling without being raised, inviting the reader: “Open your wishful wings and follow unmarked trails/of land and sea and sky.” The poems are calm and assured; even as they speak of the depth of human loneliness, they console as they convey our commonality. I’m grateful to have read them. ~Joan Aleshire

A Joni Mitchell song complains, “I get the urge for going but I never seem to go,” and so it is with David Prather’s remarkable debut collection, We Were Birds. “Open your wishful wings and follow unmarked trails,” the speaker instructs. However, like Prufrock, the ability to move is thwarted by caution and fear: “Your safety should be your first concern,” he warns, pointing out the window at “starlings, as they rise into the sky . . .” Fear rubs against desire: “The god of self-doubt stands beside me / and whispers in my ear. / The god that holds my atoms together / is sitting in my lungs.” The speaker’s attempt to breathe in that pressurized space is where readers will find something to cling to. ~John Hoppenthaler, Author of Domestic Garden

In these vibrant poems of nature and identity, Prather exhibits a true talent for imbuing natural detail with authenticity, layered meanings, and austere beauty. But We Were Birds is so much more than that; it’s also brimming with mystery and the kinds of contrasts that speak to larger human truths. Filled with rich and accessible language, these poems are intellectually stimulating and emotionally engaging, written by someone with clear eyes and an open, curious heart. ~John Sibley Williams, author of As One Fire Consumes Another

―from the book title, The Art of Bird Identification:

A Straightforward Approach to Putting a Name to the Bird,

by Peter Dunne

First, you must observe the world

from a great distance; if possible,

as far away as the exosphere.

Mind you, the temperature and lack of oxygen

will require special equipment,

which will not be advised upon here.

It is here where you can see

nothing more

but the quickened pace of the earth

rolling around the sun,

carved-out land masses,

and wind-ripped clouds.

Take heed the spectacle before you.

You must know where to look

before you seek what you desire.

Neither Heaven nor Hell

shall be viewed in this time, nor in this space.

As you move closer,

you will be troubled

by wars and other atrocities.

This is part of the landscape

and cannot be avoided.

Birds will not nest in turmoil, but some will

use the ledges and beams of civilization.

Start in Parkersburg, West Virginia.

Start with the most common species

populating town. You will know the pigeon

by its numbers and its common clothing.

You will know it by its constant pecking

at refuse, its communal behavior in parks.

Along the Ohio River,

you may see a killdeer sorting pebbles,

or a mallard scumming exposed roots

and loosing ground into the hungriest water.

Hungriest may be a misconception

on this observer’s part;

some desires have been known

to be hungrier. Some birds,

like starlings, prefer their verse in rhyme.

They carry depictions of the universe

upon their backs, blue-black

and glittering. You will

distinguish starlings from cowbirds

by their cloaks, and cowbirds

speak in prose.

Easy to identify is the blue jay,

full of scorn. Easier yet is the cardinal,

so nothing more need be said.

Be careful as you cross borders

to other habitats. A guidebook

will be your faithful companion,

regardless of affiliations. Move

through the world at your own pace.

Disguise yourself to capture the most elusive

and exotic rookeries and aviaries

and clutches and colonies.

Do not suppose inhabitants will be friendly.

Your safety should be your first concern.

Tree leaves and wild vines

can provide adequate camouflage

for predator and prey. Migration is necessary.

Open your wishful wings and follow unmarked trails

of land and sea and sun and sky.

Some of the worry is illness,

the tiny mating clouds of gnats, the startled

and choppy flight of locusts, the ragged

white moths too grounded with the season to fly.

Gypsy crickets react to each step

like reservoir water to skipping stones.

Afraid not so much in the loss of this life

as the nearness of another. A definite weakness

splits the air, rips through sure as a crow,

the noisy, certain birds of autumn. Forcing

the predilection to haste, the need

to get things done, to take in everything,

even the wash hanging two days dry

on the line. But, it will wait, simmering

like the compound leaves of black walnuts

dropping slow and yellow and one at a time

throughout September. The rocky ground good

for nothing but tearing open fermented hulls,

while gray squirrels chisel the dark shells

all day to find the sour and wrinkled flesh.

Buttons on shirts press at the chest

to remind the body of small, round cysts

that congregate under the skin. Some days

it is all that can be done to keep from counting

them over and over, expecting more,

and hoping for less. There is nothing

as quiet as the earth, the field plowed

by gluttonous moles, destroying the roots

of jimson weed and ribbon grass to find

grubs and earthworms and anything desperate

to change in its own body, come free from the soil

and rise. Some of the worry is shared,

the nervous silver-sided minnows, the directionless

cicada song disappearing into hill after hazy blue hill.

A pebble in the shoe will coerce the legs to stop,

the hands to do what they must to continue.

Because some of the worry stays

and aches wherever it finds a place to rest,

a place to winter, waiting the long months

to emerge again as though reborn.

Blood oak we call it,

the tree my father and I

fell every autumn to keep a fire

shushing inside the iron walls

of a wood stove. A fire that burns

orange with oxygen, stealing

every second breath

we had expected to take.

We tend the flames like blacksmiths,

lurching so near

that sweat becomes a layer

of skin. There is no backing away

from this heat, for this is the pure

man’s heart in four curved pieces

of metal, the horseshoes

so bright with fire

we can do nothing but clamp

them to anvils and sledge

them broad and flat.

Even the water has something

to say. Branded

and blackened and burned.

But, this is fantasy

up here in the wood

where we chainsaw

the ringed ribs of trees,

axe the pungent, yellow flesh.

Fantasy, like riding the palomino

bareback, my hand clawed

into the mane, and a girl’s arms

clutched around my waist.

Broom sedge crawls across the land

before us, smelling of leaf mold

and dawn. And we begin

to move across the field

with nothing and nowhere in mind.

We begin to sway

with the bulky life between our legs

that needs to be fed such foods

we cannot provide.

None of this matters to the trees,

the lumbering carcasses spilled

across our paths,

and the far away ringing

in our ears when the work is done,

when the work is all, and done.