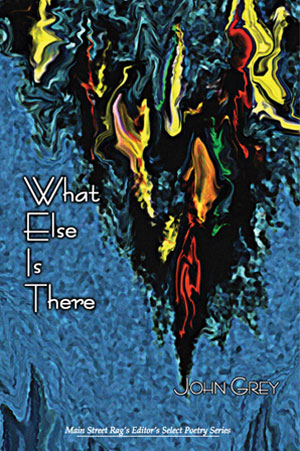

Poems by

John Grey

Poetry book, 106 pages, $11 cover price

($7 if ordered from the MSR Online Bookstore)

ISBN: 978-1-93090-746-1

Release date: 2004

A Way to Live

John Grey was born in Australia, and has lived in the United States since the late seventies. So the oft-published bio goes. He is an old friend. He is also a wonderful poet.

I have never met the man, or even seen a picture of him. He could look like Crocodile Dundee, or perhaps my accountant in New York. It doesn’t matter.

I have; however, read his poetry with great interest for more than a decade—on planes, trains, buses and boats, in the office at work and at the beach on vacation. A worthy companion. I also recently had the pleasure of publishing a broad selection of his poems in a literary journal I edit.

I say old friend because to read John’s work is to know him. And I say wonderful because in the classic sense of the word, John’s poetic vision extends beyond the myopia of contemporary culture to reveal that which we are continually confronted with yet often fail to see—the wonder inherent in the commonplace, and our responsibility to respond to it.

In “Blurb,” John addresses this directly: It’s life by process of elimination. It’s / God by default. The blurb’s instructions: You must work the work, you / must love your lover because what else is / there. In “Trick of the Light,” he writes of tracing a modest trick / back to the human dreams / of its source / where a further / leap of faith awaits. It’s an oft-visited theme in his work.

The collection you now hold in your hands consists of 65 poems written between 1992 and 2004. It is a retrospective of sorts, and represents some of John’s best poetry. And it’s very good.

John’s poetic voice is fluid and easy—more of a walk in the woods than a flash in the pulpit. He rarely, if ever, engages in linguistic pyrotechnics. His lines are conversational and deceivingly effortless, yet their economy and compaction demonstrate a rare command of form.

John is also a playwright—his plays have been produced in Los Angeles and New York—and this has clearly had a formative influence on his poetry. Almost all of his poems have a clearly defined narrative structure: not so much in the telling of an entire story, but in the presentation of an ordered sequence of events or facts. There is a causal relationship which inevitably leads to a moment of tension and release—from inaction and conflict to action and epiphany.

One of his greatest strengths lies in his ability to recognize the momentous in the momentary. He identifies—within the acts, actions and rituals of daily life—the subtext and inner meaning of minute decisions that ultimately lead to the formation of a personal philosophy. In much of John’s poetry, one can almost point to a single line—the identified moment—in which the soul of the poem emerges and (one imagines) the outpouring of words surrounding it is given birth.

In “Don’t Feed the Water Fowl,” he writes there’s an underlying horror / in every line of these park rules / at what would happen were / the jug of life to be upset. His decision: I toss my bread upon the waters anyhow, which leads him to find the hunger, the brute insistence, / of all such signs / suddenly lifted from me. His decision is the creation of individuality; his bread, the stuff of a life lived, not just passed.

In “Loving You In Winter,” John says, I learn to live / in simple spaces, / in the loss of color / everywhere but here. In a broad sense, this could be applied to all his poetry: sudden bursts of brilliant color in a world we mislead ourselves, or are misled, into seeing in 256 shades of gray. Grey is better.

The late Joseph Campbell, in his writings on mythology and religion, speaks of finding your bliss. I think Campbell would have liked John’s poetry. John’s search is, quite simply, for a way to live in a world which is not always as we would have it—but could be, if we tried a little harder.

Read, enjoy, and find a new old friend.

JeanPaul Jenack

Editor, SpinDrifter

Don Pedro Island, FLMay, 2004