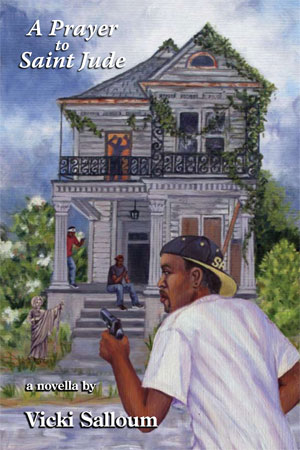

A Novella by

Vicki Salloum

160 pages, $13.95 cover price

ISBN: 978-1-59948-362-7

Release date: July 2012

Synopsis

It is a dusty spring morning in the Big Easy and Willow Jewett is on her way to Orye Majeen’s house to tutor the African-American short order cook in remedial English. From this innocent beginning, the 32-year-old white middle-class teacher finds herself plunged into the nightmare world of the New Orleans street drug trade.

As Willow, Orye, 33, and his neighbors struggle to keep the thugs from terrorizing their 6th Ward neighborhood, they come up with a plan to redeem and revitalize the deteriorating area by creating a gourmet café in an abandoned corner bar.

When the drug gang retaliates and all hell breaks loose, Orye contrives to impose a street justice that is as brilliant as it is heroic. Willow responds with a prayer to Jude, the saint of impossible causes. The result of this alliance will inspire and confirm the power of the human spirit.

Vicki Salloum

Vicki Salloum’s debut novella, A Prayer to Saint Jude, was a finalist in the 2009 Sol Books Prose Series and a semi-finalist in the novella category of the 2010 William Faulkner-William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition. Her writing credits include stories in Oxford Magazine, Rockhurst Review, The Hurricane Review, Straylight, Cooweescoowee, and Trajectory. Other stories have been anthologized in When I Am An Old Woman I Shall Wear Purple (Papier-Mache Press, 1987);Pass/Fail: 32 Stories About Teaching (Red Sky Books, 2001); and Voices From the Couch (America House, 2001). An excerpt from her novel-in-progress, “Faulkner & Friends,” appeared in 2006 in the anthology Umpteen Ways of Looking at a Possum: Critical and Creative Responses to Everette Maddox (Xavier Review Press). Vicki is a former journalist who has taught writing classes as an adjunct instructor at colleges and universities in the New Orleans area. She was born in Gulfport, Mississippi, and has an MFA in creative writing from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. She lives in New Orleans with her husband, Wayne Holley.

St. Jude, Patron saint of things despaired of, what can a writer say about a situation that is impossible in spite of the best intentions of caring individuals? Perhaps, prayer is the only answer. Vicki Salloum has written A Prayer to St. Jude for a world heavy burdened with people who live as neglected animals. The starving eyes of their big bellied children stare at us from all our windows on the world. In this novella she has managed to write about our impossible cause in glorious, evocative prose with respect and dignity of purpose. She looks deep into the hard eyes of the vengeful children who live miserably in our own backyard and offers a small but significant answer: Beyond prayer each one of us can show one child there is the possibility of something better.

–Lee Meitzen Grue,

Author of Downtown and Goodbye, Silver, Silver Cloud: New Orleans Stories.

Reading this novella is like grappling with a wild jaguar: lean, powerful, dangerous, mysterious, beautiful, perfectly formed, and utterly true to itself. From the first to the last page, the narrative never lets up its level of intensity. Vicki Salloum Holley succeeds in rendering the dark side of pre-Katrina New Orleans. With the publication of this work, she deserves to join the ranks of the very finest Southern women fiction writers.

–Julie Kane, Ph.D.

Louisiana Poet Laureate, 2011-2013, and

author of Jazz Funeral and Rhythm & Booze

A Prayer to St. Jude is more of a wail than a prayer, an impassioned cry from a blighted ghetto peopled by murderous dealers, pit bulls, grieving mothers, and crucified mentors. The scenes are hair-raising and often violent, yet a miraculous café arises amidst this desolation, much as in Carson McCullers’ Ballad of the Sad Café. Community rebirth out of collective destruction has become a classic New Orleans theme, and here Vicki Salloum leads us on a harrowing journey through the city’s heart of darkness, gathering glimmers of hope along the way.

–James Nolan,

author of Higher Ground

and Perpetual Care: Stories

I.

lead me, guide me

I don’t know whether it is awe or shock that strikes me as I walk down the dust-blown, potholed New Orleans road that could be a main street of Hades. Carried by a strong May wind, loose blown from a cross street that seems never to have been paved, sand whips across my face, temporarily blinding me as I pause then hurry on. I am on my way to Orye’s. I thought it would be easy to get off the streetcar at St. Charles Avenue and Rhine Street and head up Rhine till I hit Krakow Street, for I love walking. But as I pass through every block, each worse than the one before, I begin praying for my life.

Each more dilapidated and menacing than the one before. Seven blocks into my walk, I see a petite Victorian cottage that in better times would be adorable spray-painted with obscenities, on the front, sides, stoop. How anyone could be so brazen. Worse still, where are the owners? The signs of protestation? The cottage branded on a spring morning. And the silence of the morning, the helplessness (like the strays all around, starved, fragile, beyond the reach of all protection), coupled with the acquiescence, as if dust whirling about the sky paralyzes all outrage, are profanities of their own.

I find Krakow and take a right, moving swiftly. I will find his place–in the 2600 block–ring the bell, walk in, then not go by foot again. It is nine in the morning but so hot sweat drips off me. In the next block, every other house is boarded up. In one, a corner building, boards are nailed across windows and in the few that are free of them all I see is broken glass, jagged shards like sharp cat claws. The entrance is one left shutter door, the empty hinges of the other allowing a clear view inside. I see a hand move in the space beyond the missing shutter and suspect someone still lives here. The clapboard walls are bare of paint, except for the spray-painted “RIP Rashad.” Vines creep and crawl across walls to the tar-black roof above.

Farther down are equally squalid buildings, boarded up, burned to ashes, one back yard nothing but amber weeds, tree stumps gold and eerie. I start at a loud squawking and flapping. Only pigeons escaping from beneath a house. My heart still pounding, I come upon a schoolyard and a student’s menacing glare. “Why you here? Whatcha doing!” an angry voice bellows. It belongs to a stocky man yelling at the boy. The man turns his gaze on me. For an instant, I feel like a criminal, then remember I’m a middle-class white woman who’s never done an illegal thing in her life. And all I’m doing now is walking down a street, though there can be no doubt I don’t belong here. “You ain’t suppose to be out here stupid ass,” the stocky man insists. “Get back in your classroom.” As I keep walking, I ponder his words and think I must have misunderstood. No teacher would call a student “stupid ass”. Maybe he’s calling out the boy’s name, a name that sounds like stupid ass, then I try to think of names that sound like stupid ass but can’t for the life of me.

I think about what I told my husband one morning after scanning the local paper. I’d read a story about a teacher who was suspended from a public school for calling a student a slut, and I turned to my husband Luke and said, “I’ve never called a student a slut,” and Luke turned from his breakfast cereal and feigned deep admiration. “That’s terribly professional of you,” he proclaimed. “Knowing your students, I’d say you’ve acted with commendable restraint.”

I walk on, am startled once more. In the next block, a two-story giant of a Greek Revival is covered in vines, crawling up the front and sides, intertwining the columns and gallery, saturating every inch of the side of a mammoth roof, crawling through second-story windows and invading inner sanctums of high-ceilinged bedrooms. I can’t stop staring.

Down below, two boys sit on a stoop. Eyes fixed in bored defiance, their feet propped up and cigarettes lit, glancing about the neighborhood, hungry for distraction. They spot a boy heading their way. The boy bangs a tree branch against anything he can find: tree, junk car, trash can. Takes out a knife from a pant pocket and hurls it at the ground. He dislodges it, puts it back inside his pocket and joins his buddies on the stoop.

I hurry down the block, hoping I’m getting close. Take out a scrap of paper from my purse with Orye’s address scrawled on it–2614 Krakow Street–and know the house must be nearby. I pass a vacant lot with weeds as tall as corn, and beyond it, see a roof, a single pigeon perched upon it. As I walk farther on, I see the rest of it: A tall, towering building, well over two hundred years old, derelict. Yet, it’s the address Orye has given me. Surely he’d written down the wrong address. Surely there’s an explanation. It is three stories–gigantic–vastly taller than anything surrounding it. It reminds me of a great fortress, or a lone elephant, standing on a vacant acreage of land. Most of the paint has been stripped off, and what remains is greenish-yellow. Ten iron-black steps ascend to an elevated green door and, above it, high upon the third level, another green door opens onto a tiny platform. And there he stands, high upon the platform, leaning forward against a rail. From there, he looks down. The same eager-friendly face, eyes seemingly oblivious to the glare of hideous reality, ears deafened to the screams of a tortured animal shrilling the air, pretending all is right, only the merest glint of anxiety bubbling from beneath, signs of his real intelligence.

He waves. I smile. He disappears. I know he is coming down to treat me like British royalty. And we will both pretend. It is a pretense I can live with. I have no second thoughts. I will not take back any moment of what I know will be the most ridiculous role I will ever play. I pray no harm will come. I do not belong here with the dead grass and jagged shards for windows and shredded strips of cloth beyond panes like images of tiny animals and criss-crossed vines encroaching on ghosted rooms. But he belongs here less than I.

Apparently, he can’t descend the steps and come out through the green door, for I hear him calling from the side. He leans out a window on the right side of the building, beckoning me. He disappears as I approach the side door that faces a cross street named Sapphire, and, finally, stands in the doorway, looking excited as I come nearer. So excited, he doesn’t see the horror: a black lump across the threshold, what appears to be a dead animal. In his eagerness to greet me, he trips over the lump and lands face down, his cane falling in front of him. In his rush to remedy his embarrassment, he reaches for the cane, struggles to regain his footing, but I recognize in his eyes a look I’ve seen before.

The first time I ever saw him when he came into my classroom, I saw that look then. Orye stood about five-foot-nine-, a solidly built man with a round face and bug-eyes. He looked to be about thirty-three, only a year older than I. I remember calling his name from the roster of names and thinking I could always remember him as the man with the bulging eyes. I stumbled over his name, and he politely pronounced it for me–O and rye, like rye bread–and the last name, Majeen. Orye Majeen. And after class, he approached me and there was an aura about him of such haunted desperation I knew he was frightened of something.

He indicated to me that he feared he would not pass my class. By whatever means I knew, I was certain this was no minor matter but central to his entire being. He asked if I could help him. I cannot recall his exact words. I can recognize in someone’s face the sense they’ve been consumed by an insurmountable problem. And I wanted to help in any way I could. I tried to reassure him everything would be fine-he would do fine-but the look told me he didn’t believe me. In my ignorance, I thought the fear had to do with me-he had no confidence in my teaching-but now I know this was not his thinking.

When was the first time I suspected? It wasn’t even after I’d given that first grammar quiz. He was the last to leave the room. He was not only the last to leave, he stayed a full hour after the others had gone. I sat at my desk watching as he wrote frantically, the frustration mounting, and couldn’t help but feel sorry for him, feel a respect for his efforts, for he had no intention of giving up. It was getting late, going on ten, for this was an evening class, and I was anxious to get home. Finally, I told him to turn in his paper. And even with that extra hour, he got almost every answer wrong. Even then, I didn’t suspect. I guess I had confused strength of character with something else. I thought he was one of those students, normal in every way, who’d never been taught the basics in all his years of schooling and now, in community college, found it impossible to catch up. Most of my students fit into that category. This was the lowest level remedial English class, filled with adults who’d been out of school for years, who’d gone to the worst schools taught by the most indifferent teachers and received the most reprehensible kind of education. Only when he handed in his first essay did I realize the problem went deeper than that.

When I saw his paper, I couldn’t believe it.

If you would like to read more of A Prayer to Saint Jude by Vicki Salloum, order your copy today.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.