Reader, you may have been waiting for something like this. Hodges authenticates his characters in a flash, their motivations and intrigues swirling about like those of real humans. This thing has the ragged, rambling feel of real life–the kind worth living–but contained in an artful, unified atmosphere that feels charged and tenuous and undocumented. And the language, of course, is no small part of the effect–the kind of firecracker language that, once engaged with, is difficult to do without. To put it simply, this novella is infused with a raw energy that makes most other reading materials seem tame.

–John Brandon

The first seven words of this amazing work are a more effective recommendation than any I could write. Do you love them? Do they scare you? Either way, you need to keep reading. Hodges reminds us — and we’re so smart we need reminding — that fiction has the power to exhilarate and terrify, to take us to the highest and lowest places in our awful hearts. Without imitating or bowing to anyone, he is a real spiritual heir to his great mentor Barry Hannah. Sooner or later he will get you. Why not now?

–Jack Pendarvis

War of the Crazies is a lyrical screed, an act of terrorism, a fevered excoriation of American wastefulness and abjection. Hodges’ post-punk sensibility and its attendant rage generate a psychic viscera that will no doubt discomfit many a reader, but these are not the placental mewlings of a rebel without a cause. Rather, Hodges’ perceptual acuity, fearlessness, verbal energy, and sobering empathy for those marginalized by their failure to adhere to the madnesses of the larger culture mark him as a serious anti-artist. Much like his character, Noyo, the proprietor of an herb farm that is one part commune, one part radical think tank, one part Eden, and many parts junk, Hodges scavenges our cultural waste to produce new vitalisms, and in this case, we are gifted with a novella that a flea market cyborg wrought from fishing wire and cans of Milwaukee’s Best Ice might have dreamed the night before it launched an assault on the World Trade Organization. Hodges’ prose disdains the practiced and often polite etudes of the common, celebrated literary scribbler, and instead outwrangles a heretical and holy voice earwigging us toward the extinction of our ecstasies and dooms.

–Tim Earley

Chapter 1

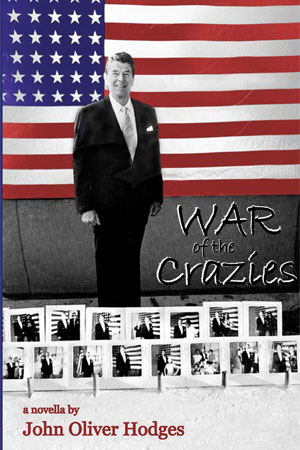

Ronald Reagan was nailed through the eyeballs, nailed through the kneecaps, nailed through the foot bones, and nailed between his legs to the ceiling. It wasn’t the worst person to see floating above you as you lay in bed ruminating over your day. Ruth’s day had been strangely long, and full of so many distractions that she’d all but forgotten how lousy she was supposed to feel. Lewis’s funeral now seemed months in the past, yet she still had a bruise from where Mr. Crabb yanked her arm. “That’s my daddy’s grave you standing on!” he’d said. The Crabbs blamed Ruth for what happened, and they were right. If not for her, time would have been switched up differently, and Lewis would not have crashed his bike. Better had they never met. Ruth was beginning to love that quirky smile on Ronald’s face.

“Ruth!” came Noyo’s voice.

It was time to go to the town board meeting.

“Silva!” went the voice.

Ruth stayed in bed, and listened to Silva’s rattlesnake boots clomp down the stairs. When Silva reached the bottom, Ruth rose and stepped through the library on into the kitchen. She was greeted by Silva’s owly face, which seemed fresher now, relaxed and silly.

“OK!” Noyo shouted, and clapped his hands together. “Let’s go show the town board the pictures.”

Outside the world looked frosty and brittle in the falling snow. Ruth opened the gate and the van rolled through and she shut it and climbed in, sat on Silva’s lap in the passenger seat. Silva wrapped her arms around Ruth and they looked out the window as Noyo drove along Fish House Road, singing German war songs. Noyo sang beautifully. Ruth and Silva had their own personal opera going on.

Soon they were driving alongside the Great Sacandaga Lake, a strong wind whistling through the van’s cracked window, a fine accompaniment to the strange words issuing from the mouth of the Italian. The dark lake stretched out in thousands of sharp wavelets jumping up into white nipples spewing milky sprays.

“Get me off the beach,” Silva said, cutting into Noyo’s song.

“I’m sorry?”

“The draft.”

“Is that a complaint?”

“Yes it’s a fucking complaint.”

“This is good,” Noyo said. “You need to be angry when we get to the town board meeting. You need to be angry about they want to tear down a perfectly good eh’nudding wrong widdit house. Tell them you have been so excited about when the house is fixed so that you can live in it. Maybe you and Ruth can act like poor peasants that need a place to live for them to feel sorry for you, yes? We need to work together. You need to tell them it is your dream house.”

“Houses are stupid,” Silva said. “Do you think I care about any house that was ever built?”

“Houses are not eh’stupid,” Noyo said.

“That’s for me to decide,” Silva said. “What about that draft, bitch?”

“I’m sorry,” Noyo said. “This window does not eh’close all the way. But look, we are here.”

Noyo pulled the van into a gravel lot where trucks and cars were parked in front of a red building that was trying to look like a barn. A large plaque above the door read: GIVE HER A CARROT.

“Good God,” Silva said.

Noyo parked. “Dick Ryder is the owner of Give Her A Carrot number seven,” he said. “Give Her A Carrot did not do very well in the races this year from what I have learned.”

“Give Her A Carrot had muscular dystrophy,” Silva said.

They took the steps, went inside where the meeting was already in session. About twenty heads turned to look at them. “Have a seat, Mr. Bojojovich,” said the man with a waxed mustache. Noyo and Silva and Ruth sat down, the other people in the room still shaking their heads over the rudeness.

The discussion at hand concerned the county landfill and whether or not people should be allowed to carry things out of it when they went to dump things in it. “There’s a reason people throw away what they throw away,” said the man with the mustache. His smooth steady voice carried with it a quality of uncompromising conviction. He sat behind a table at the head of the room, his head the size and shape of a small watermelon.

Noyo leaned over and whispered in Ruth’s ear, “That idiot is Dick Ryder.”

“It’s been brought to my attention,” Dick Ryder said, and cleared his throat to lay emphasis on what he was to say next, “that several unnamed Broadalbinites make regular trips to the landfill and sometimes they don’t bring anything to contribute to it, but as previously mentioned, remove things, entire vanloads of items other citizens intended for permanent disposal. There is nothing in the ordinal pertaining to this procedure, and being it has been brought to my attention, certain complaints I should say, about the discomfitures of having personal belongings carted off for unknown purposes, I feel it my duty as chairman of the board to see the matter resolved.”

Noyo stood up.

“Mr. Bojojovich?” Dick Ryder said.

“I would like to know who made this complaint you are eh’talking about.”

“That’s confidential, Mr. Bojojovich. I will say this, however. I believe all persons present hold to the idea that what they throw away, in a very poignant sense, is not to be disturbed, re-earthed, as you will. Last week the mother of one of our oldest families told me she was on her way to Gloversville to see her chiropractor when lo and behold, a van turned out from an approaching street with her mother’s chiffonnier strapped to the top of it. She was appalled, and I should say, rightly so. Such items are personal and–”

“There was eh’nudding wrong widdit!” Noyo cried out.

Laughter.

“Well, I guess now we all know who stole her mother’s chiffonnier,” Dick Ryder said.

The whole room rose up laughing.

“I did not eh’steal it,” Noyo said. “Why would anybody throw away her mother’s belongings in the first place? You talk about appalled. What do you think I was when I saw a nudding wrong widdit chest of drawers in the garbage?”

“I bet he was happy,” somebody said.

Again, the house rose up laughing.

Dick Ryder held up his hands, turning his head slightly to the side for everybody to see his beautiful brown chops. It was a gesture that said to all present that, Wait, let us wait, we must deal softly with this Italian, speak to him as a child, let us do what we can to mollify him. Dick Ryder put his hands down flat on the table and cleared his throat. “Whether it was, as you say, nothing wrong with it, is beside the point. The issue we are dealing with is that what our citizens throw away is not to be dragged out of the landfill and revived for unknown purposes.”

“What purposes?” Noyo said. “What else do you use a chest of drawers for but to put things in?”

“Even pearls. If somebody throws away pearls,” Dick Ryder said, “they should be left where they lie.”

“Ehhhh, I did not find any pearls,” Noyo said.

“That’s irrelevant!” Dick Ryder said, losing patience.

Noyo looked around at the people in their fold-out chairs.

Most of the people turned their heads away, but one person, a logger, said, “If I caught somebody stealing my mother’s chiffonnier, I think I’d be looking for somebody.”

“This is eh’crazy,” Noyo said.

“You calling me crazy?” the logger said, getting out of his seat. He wore a woodsmanly shirt, a barrel-chested tough guy, him.

“No, I did not. I said it is crazy. This is crazy. It is genocide. You throw away good things and you want it so nobody else can have it. What kind of eh’thinking is that?”

“If you don’t like it, leave it,” the tough guy said, his fists balled.

“Fuck these dumbass people,” Silva said. “Let’s go.”

Milton of Milton’s Friendly Grocery Haven stood up and said, “I’ve seen Mr. Bojojovich stealing bad cupcakes from my dumpster.”

One fat woman said, “About a year ago I saw a man pedaling my daughter’s bicycle down Fish House Road. I knew where he came from. It was that hippie farm they got.”

“They pollute the creek,” somebody else said.

“I have never shit in the creek!” Noyo shouted.

“Listen to him,” the tough logger guy said. “He’s trying to defend it. I think the ordinance you’re talking about is a fine one, Dick. We should make an ordinance against ignorant people buying up property here.”

“Gene!” Dick Ryder shouted.

“Aww, Dick?”

“Not another word, Gene. We don’t need any loose cannons here tonight. Let’s not forget what happened with Delbert. Mr. Bojojovich has been at every one of our meetings. He deserves to be heard and his concerns acknowledged. Everybody in favor of restricting removal of junk from the landfill, raise their hands yay.”

Most of the people in the room raised their hands. “OK,” Dick Ryder said, and slammed an antler on the table. “Ordinance number two-seventy-two will be no junk shall be removed from the landfill without the written approval of the party who did the initial throwing away of whatever items that might be drawn into question.”

“Eh’stupid!” Noyo said.

“I beg your pardon?” Dick Ryder said.

“Look,” Noyo said. “I will not let you tear down my house when so many other houses in Broadalbin are worse than mine. I have proof.”

“Proof?”

“Pictures. I have pictures right here. Look at these houses, and then look at mine. You cannot tear down my house until you tear down all these others that are in eh’worse eh’shape than mine.”

“Let’s see the pictures,” Dick Ryder said.

Noyo walked to the front of the room and set the Kodak-stack on the table. Dick Ryder examined them, saying, “Yes, yes, yes, oh, that one, yes, well, you’ve made your point. We’ll give you seven days to get it in shape. Then we’ll inspect it. If it doesn’t hold up under the code we’ll have the demolition crew out the following day. You must understand, Mr. Bojojovich, that several important families have ancestors in that graveyard and they don’t like seeing such an obnoxious structure blocking its view from the road.”

“I understand,” Noyo said. “I fix it up in seven days. It will look eh’very good from the road.”

Then in the van where Napoleon and Ugly were shivering, their doggy skins racked against their doggy skeletons, Noyo started the engine and drove through the snow-blowing air. “Idiots!” he shouted.

If you’d like to read the rest of the story, order War of the Crazies by John Oliver Hodges today.

John Oliver Hodges attended high school in Florida, where he played guitar for the punk band Hated Youth, and crashed his motorcycle head-on into a green car. The insurance money he spent on Kodak film. He became a photographer and traveled through Europe and Mexico. After years of wandering and working in factories to support his photography, he flew to Alaska to commune with nature. Then it was to Oxford, Mississippi, where he studied fiction at Ole Miss. His short stories have appeared in Swink, StoryQuarterly, American Short Fiction and The Literary Review. He currently lives in New York, and teaches writing at Montclair State University in New Jersey.

John Oliver Hodges attended high school in Florida, where he played guitar for the punk band Hated Youth, and crashed his motorcycle head-on into a green car. The insurance money he spent on Kodak film. He became a photographer and traveled through Europe and Mexico. After years of wandering and working in factories to support his photography, he flew to Alaska to commune with nature. Then it was to Oxford, Mississippi, where he studied fiction at Ole Miss. His short stories have appeared in Swink, StoryQuarterly, American Short Fiction and The Literary Review. He currently lives in New York, and teaches writing at Montclair State University in New Jersey.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.