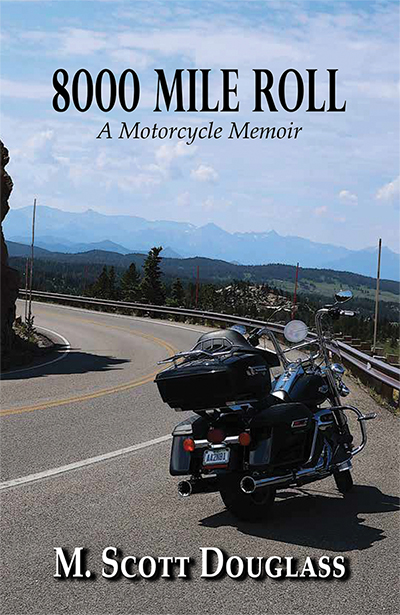

8000 Mile Roll

A Motorcycle Memoir

by M. Scott Douglass

Published by Paycock Press, Arlington, VA

ISBN: 978-0-931181-85-6, 318 pages, $19.95 ($15 if ordered here)

Release/ship date: April 2, 2024

The prepress price on this has expired. Those who prefer to pay by check, the preorder price is $19 (including shipping) and should be made payable to M. Scott Douglass and sent to Main Street Rag, 4416 Shea Lane, Mint Hill, NC 28227.

To order bulk or direct from the publisher, Paycock Press, please visit their website: https://gargoylemagazine.com/books/

Synopsis

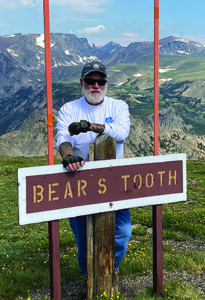

In 2021, in the fading days of the pandemic, M. Scott Douglass took a motorcycle ride across America. The ride itself took 24 days and covered 8001 miles through 24 states with extended stops in the Grand Canyon area and his native state of Pennsylvania. This book is a journal of that adventure, the places where he went, and the people he met along the way.

M. Scott Douglass calls his 8000 Mile Roll a “Travel Memoir.” Okay, whatever label works. For me, this work reads as if I ran into him at some roadside diner, he grabbed me by the collar, sat me down in his booth, bought me a beer, and said, “Man, I have got to tell you what happened.” And I am there all night surrounded by empty bottles, engrossed in one part of the journey after another, right to the end, which really doesn’t end at all, since Douglass makes me want to chuck it and head out with him across America, and not many writers today can do that. ~Bob Kunzinger, author of Borderline Crazy and The Iron Scar: A Father and Son in Siberia

It’s impossible to read Scott Douglass’s riveting new memoir, The 8000 Mile Roll: A Motorcycle Memoir, and not conjure Steppenwolf’s “Born to Be Wild,” the revving, reverberating anthem to the iconic film, Easy Rider. In prose just as outrageous as a jacked Harley engine, Douglass spins out a tale of derring-do and adventure. If you love the promise of the open road, the wind in your face and the wild and welcoming world’s seductive beckon, then snag this explosive book. ~Joseph Bathanti, North Carolina Poet Laureate (2012-14) & author of The Act of Contrition & Other Stories

The Return of the Great American Road Trip. Wanna get away? Then hop on the back of M. Scott Douglass’s Harley Road King and hang on for dear life! Eight thousand miles later, you’ll know you’ve been somewhere baby! – James J. Patterson, author of Bermuda Shorts and Junk Shop Window

Introduction

I started riding motorcycles with Scott Douglass about a dozen years ago. We met a couple years earlier at a poetry reading I attended with my now-wife, Anne. She, like Scott, is a poet, editor, and publisher, and had known him ten years already, professionally and as friends. At some point, I revealed to Scott how I fell in love with motorcycles at age six, after my favorite uncle took me riding on his Honda 350. I bought my first road bike at 20, and an unbroken succession of motorcycles have moved through my garage in the subsequent forty years.

When he and I began riding together, it quickly became clear to me that we share a nearly indescribable mindset about motorcycling. Scott has logged the vast majority of his miles alone or in the company of only one other rider, just as I have. For both of us, that solo experience has revealed a mental harmony on a bike that is quite unlike any other.

Safe motorcycling requires a kind of “hyperawareness” as your senses are continually assaulted by so many factors: balance, acceleration, braking, wind, heat, cold, noise, vibration, and the crush of visual input from speeding down the road. Some of us, not all, find this hyperawareness becomes automatic and discover a mental state of contemplation and creativity on top of it that I have never duplicated elsewhere. In essence, our minds wander, but never from the road. I see how this “Zen” impelled Scott to make a cross-country tour and record his adventures.

Scott first mentioned the idea of riding to Los Angeles and back in 2019. By then, he had taken several thousand-mile-plus solo trips within three or four days. This trip, he told me, he wanted to race across the country on major highways in four, six-hundred-mile days, visit his friend Steve for two days, then race back, all in about a week and a half. I scoffed at the idea. “What’s the point of flying down the road like that? You may as well drive your car. Or fly.”

Work and life commitments initially kept the idea at bay, then the pandemic placed a firm hiatus on it. During that time, Scott’s plan morphed into a month-long loop of places he had never been, with a wedding anniversary excursion in the middle that you will read about. In the months before the June 2021 departure, he meticulously planned each day of travel, using Google maps and aerial views to select interesting backroads and rural routes for much of the trip.

The book starts with Scott colorfully recounting a handful of life milestones—beginning at age three—that reveal his deep-set motivations for this adventure. Then we see how he equipped the motorcycle and himself for the journey, and get hints of what Scott hopes to find along the way. Next, the Harley-Davidson rumbles to life, and bike and rider roll down the drive.

Heat, questionable accommodations, dicey meals, rough roads, beautiful sights, and a number of interesting characters highlight the trip. Along the way, we get a sprinkling of Scott’s thoughts on road design, bad drivers, eighteen wheelers, politics, and the dynamics of extended family, all conveyed with a bit of the Zen contemplation described above. And a dash of Scott’s trademark subtle sarcasm.

Scott shares twenty or so songs that popped into his head while on the road. I can personally relate as this so often happens to me. He mentions Seals and Croft’s “We May Never Pass This Way (Again)” in Chapter 14, and that sense surely permeates much of this story. What Scott experienced—interactions, sights, smells, and sounds—is profoundly significant because it can never be duplicated exactly.

I applaud Scott not only for taking this adventure, but also for recording it so adeptly for others to share in. If I ever get around to writing the novel that’s in my head, it will be about my fictional construct of “The Writers Block Motorcycle Club.” The club’s motto is “The Road Beckons.”

Enjoy the ride.

James Kaylor

Editor, Moonshine Review Press

Lifelong Motorcyclist

Friend

Prologue

In the Wizard of Oz, Glinda, the Good Witch, told Dorothy she must start at the beginning if she wants to go somewhere, then led her to the spiraling center of the yellow brick road. It was an exciting moment, a grand display with music and a chorus of munchkins pointing to the path that would lead Dorothy from where she was to where she was told she needed to go.

Of course, her journey didn’t really start there. It started in a Kansas farmhouse. It started by running away from that farmhouse, from the safety of family and into the unknown. And isn’t that the true nature of adventure: To leave one place and go somewhere you haven’t been before? To get away, escape?

As I think back, I’m sure I understood the concept of escape before I knew the actual word. It was a matter of finding myself someplace I didn’t want to be and looking for an alternative, someplace else I couldn’t imagine because of my age. But it wasn’t here, there, the apartment in which we lived, a room in which I was caged.

I’m only guessing 1959, but I’m certain about the place, an apartment complex in Crafton, Pennsylvania. When I think of this place, this time, this event, I still feel the dampness in the air, smell the must of decaying leaves. It seemed like it had rained forever, but time is skewed in the mind of a child. Rain had surely fallen for days, maybe a week, a cold autumn rain that permeates skin all the way to the bone.

Then, abruptly, it stopped.

The little girl who lived in the building across the courtyard was outside. She had a tricycle on the sidewalk in front of her building. Her mother sat on the stoop above holding her younger brother. I coveted that tricycle like nothing else because I didn’t have one of my own. Studies or rumors must have labeled them unsafe, and my mother forbid me from having one. But I could see one from our second-floor window, rocking with its passenger, a few feet one way, then back, on the sidewalk across the wet grass, a million miles away. And she didn’t even know how to ride it right, pushing it back and forth with her feet on the ground instead of pedaling.

I don’t remember where my mother was, what she was doing or how I opened the door, climbed down the stairs, and stood on the sidewalk in front of our building to watch. I do remember the little girl throwing a tantrum when her mother stood to go back into the building. She stomped her feet, knocked that beautiful tricycle on its side, screamed.

I ran to the rescue.

A hundred feet can feel like a hundred miles when your legs are less than a foot and a half long, but I got there, pulled the trike upright, and proceeded to make my getaway. It didn’t go unnoticed. The little girl screamed even louder, but her mother, already immune to her vocal demands, hands full, body facing the entranceway, must not have seen the heist in progress. The little girl ran around in front of me, her arms straight, palms out in a halting stance, and ordered me to stop. That’s when I ran her over.

Okay, maybe I just knocked her down, after all, how much momentum can a toddler generate while pedaling a tricycle made for a three-year-old? The result was the same. She fell backwards on the wet pavement in her white dress, banged her head, and cried. Then the whole world collapsed around me.

I’m told moments like this were common in my younger years. This one stands out because of the trauma that followed. I hated that little girl as much as any 3-year-old could hate. She would taunt me with her trike, hit me, and tell me I couldn’t hit her back because boys weren’t allowed to hit girls. In retrospect, she likely had quite an awakening over the years, but that was the consensus opinion of the day. Every time I’d tell my mother of the little girl hitting me, she’d remind me that I couldn’t hit her back because she was a girl.

I don’t recall deriving any emotional satisfaction from knocking her on her butt while stealing the trike, but I’m sure it existed. Anyone shocked that I’d place such thoughts into a three-year-old’s mind, stop living in denial. We all have violent thoughts, even when we’re young, and I paid a price for this one. I may not have known the word escape at the time, but I absolutely knew the concept of an ass-whooping and this attempted trike theft incurred the wrath of Mom.

A parent could do that back then. It wasn’t unusual to see a mother grab her kid by the arm, ear, or collar, drag them from a store to the car, swatting them on the ass the whole way. Some of us felt shame, embarrassment when we saw this happen and thought, uh, uh, not going to be me. We allowed the fear of public humiliation to teach us how to act like proper citizens. Others learned by being the example. My younger brothers benefited greatly from my ground-breaking activities.

This is my earliest memory of attempted escape. I’m told they became so commonplace that my mother would sometimes pack me a lunch. You have to wonder what puts the idea of escape into a toddler’s head. I didn’t grow up in a tough environment—certainly not at that age. No one had ever locked me in my room or instituted unreasonable rules. It might have been the second-floor window, seeing others come and go and wanting that same freedom for myself.

I remember this girl because I’ve met many like her since. I remember this attempted escape because of the consequences that followed. Either memory could be triggered by a movie, a photograph, a story, an image on a computer screen, or another person’s anecdote. Together they reinforced a longing to get away, to explore or refresh a feeling brought on by the memory of someplace I’d been, the process of going, the reward of arriving.

My yellow brick road had no swirling beginning. It wasn’t a direct or indirect route to a specific place. It wasn’t even yellow. There were potholes, bridge outages, downed trees and just about any time someone told me which way to go, I went another. For me, escape and following someone else’s footsteps were always different things, the latter being something to avoid.

M. Scott Douglass grew up in Pittsburgh and lives near Charlotte, NC. He’s Publisher/Managing Editor at Main Street Rag Publishing Company, a Pushcart Prize nominee, and North Carolina ASC Grant recipient. His poetry has most recently appeared in North American Review, Kakalak 23, Twelve Mile Review, Salvation South, among others. His graphic design work has earned two PICA Awards and an Eric Hoffer Award nomination. Previous books (poetry) include

M. Scott Douglass grew up in Pittsburgh and lives near Charlotte, NC. He’s Publisher/Managing Editor at Main Street Rag Publishing Company, a Pushcart Prize nominee, and North Carolina ASC Grant recipient. His poetry has most recently appeared in North American Review, Kakalak 23, Twelve Mile Review, Salvation South, among others. His graphic design work has earned two PICA Awards and an Eric Hoffer Award nomination. Previous books (poetry) include